Advertising fraud in mobile

Eric Seufert, vice president of acquisition and user engagement at Rovio, spoke about fraud in mobile advertising. And how to deal with it.

The original version of the material can be found on Mobile Dev Memo, a website dedicated to the mobile industry, run by Eric Seferth himself, author of the book Freemium Economics.

On December tenth, AppLift, together with the company Forensiq, which is engaged in tracking cases of advertising fraud, published a study where it shared disturbing information about advertising fraud in mobile:

- 34% of all mobile traffic may be fraudulent (of which 12% may be so with a high probability, although the study does not indicate the difference between “may be fraudulent” and “may be fraudulent with a high probability”);

- CPM campaigns are three times more likely to attract fraudulent clicks than CPC campaigns (which are 10 times more likely to attract fraudulent clicks than CPI campaigns);

- there is no significant difference between the number of fraudulent ads on iOS (33%) and Android (35%) (in other words, it will not be possible to reduce the risk by focusing on one platform to the detriment of another).

The authors of the study provide interesting information: fraudulent advertising is divided into two types (technical fraud, that is, one that uses a certain technology to deceive the system, and fraud that exploits platform vulnerabilities), and also differs in the ways that fraudsters resort to in each of the cases.

Mobile fraud is undoubtedly a serious problem for mobile developers: spending on mobile programmable advertising in the United States in 2016 will reach $8.36 billion (exceeding PC advertising figures), and according to Forensiq forecasts, advertisers’ losses from fraudulent mobile clicks by the end of this year may amount to $1 billion. In another study, the mobile analytics firm Apsalar found out that globally, there are 2.57 fraudulent clicks per 1 real click leading to an installation.

In an interview devoted to the study, the CEO of AppLift claims that among the ways in which advertisers can fight fraudulent advertising in mobile is the optimization of click campaigns and user activity. In other words, it is necessary to reduce the costs of those campaigns that do not lead to installations and/or user activity in the application, since bots and other traffic sources are not able to simulate them. Although this is true, this approach shifts part of the responsibility onto the shoulders of the advertiser, while the responsibility should be borne by advertising grids, since they make it easier for fraudsters to access applications. In addition, this approach does not provide complete reliability: even if we assume that fraudulent clicks are somehow evenly distributed among all the advertiser’s applications (which, to put it bluntly, is hardly possible), optimization algorithms aimed at activity within the application may not be able to divide with the necessary accuracy and confidence traffic sources are divided into “bad” and “good”.

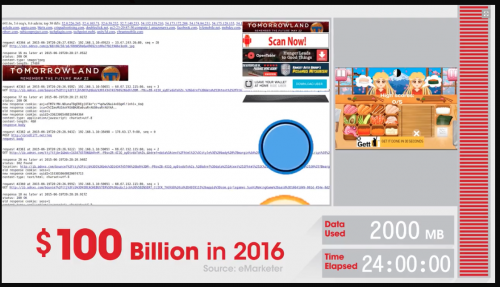

One of the extremely problematic forms of advertising fraud is the so-called “hijacking” of applications, which was described by Forensiq this summer. Certain applications launch a lot of advertising banners (up to 20 per minute) and even simulate clicks on these banners, which makes sense of the optimization method described above. These applications can even launch pages with advertising banners so that the user does not notice it, thereby gaining a huge number of impressions/ clicks and simultaneously putting the battery of the user’s smartphone, as well as collecting data in the process. Forensiq deliberately launched such an application, and it turned out that in 24 hours it is able to upload 2GB of images and videos from advertisements.

Another way advertisers can fight fraudulent advertising (or at least not incur financial losses) is that advertisers need to negotiate with advertising networks about the terms of placing an order. Advertisers should exclude “unwanted installations” (that is, installations that were carried out by someone other than the CA defined in the terms of the order placement) from the payment agreement. This, of course, again shifts the burden of responsibility onto the shoulders of advertisers, but at the same time gives a scheme of actions that will help avoid payments for fraudulent installations.