Ron Gilbert: how to plan a budget correctly

Ron Gilbert, who worked on Maniac Mansion and the first two games of the Monkey Island series, recently started developing the adventure game Thimbleweed Park with the help of Kickstarter. In the blog of the project, he told how he plans the budget of the game.

I recently asked Gary [Gary Winnick, co-author of the Thimbleweed Park project, – approx. editors] and David [David Fox, programmer on the project, – approx. editors] that they are most stressed in the development of the project. In my opinion, this is a very useful exercise. It helps to understand what is bothering the team. The answers change in the process, because the work is going on and new reasons for excitement arise.

We are all concerned about the amount of work that needs to be done. He scares. But that’s okay. There was never a time when I wasn’t scared by the amount of work I had to face. If the amount of work does not frighten you, then something has gone wrong and you need to load yourself more. Let the work frighten you – load yourself exactly until you feel that this is your limit.

In the podcast, I mentioned that I am concerned about the money issue and how the bank account is decreasing every month. It all somehow imperceptibly transformed into “oh no, we’re running out of money,” which does not correspond to the real state of affairs. I’m just worried about money, like anyone who starts a project.

The story is this: if I’m worried about something, then I try not to make it a problem. It’s the same with money. If I didn’t think about them every day, they would have ended unnoticed, and that’s it.

Five hundred thousand bucks in a bank account can turn your head. It seems that this is an endless supply of loot, as it is more than many people (including me) have ever seen on their account. But you need to treat this money as if it were five thousand dollars. Or even five hundred bucks. Every dollar is important.

That’s why I’m budgeting.

One of the advantages of having a publisher is that he will find a lot of holes in your budget and question every assumption. The downside is that it will definitely understate your budget. Developers often call fake numbers in order to conclude a contract with a publishing house (on which it often depends whether the studio will stay afloat). Moreover, they do not do it maliciously, they (I also did this) just convince themselves that they will be able to meet smaller amounts. And this is often not true.

I want to know where each specific dollar is spent – from the beginning to the very end of the project. You start putting expense items in the budget and immediately see how the money is melting. I added a couple more articles – and there were none left at all. This is a sad and necessary process. You start thinking before you spend.

We made spending plans for the same Lucasfilm, but we did not see the real consequences of our work. I could make a budget for the project, and even if I exceeded it by 20%, the worst thing that threatened me in this case was a scolding from the authorities, and not that people would be left without a salary. If you run out of budget when you run your own company and finance a project out of your own pocket, your employees don’t like it. In the real world, they stop working.

I make a budget plan in the first approximation – before I start creating a project. I often know how much money I have, and I want to estimate how many people I can hire and how long I can last before I run out of money. If I have 15 months left, and I can afford 5 people, then this helps me make a plan. If the term is 24 months, and I can hire 100 people, then these are completely different figures.

As soon as I have sketched out a preliminary budget, we start working on the project and enter the pre-production phase. All this time, I continue to refine the budget, as I continue to receive new information. As soon as the pre-production stage is completed, we can already estimate the actual amount of work and make a final financial plan based on the schedule. The budget and schedule are two different documents that complement and improve each other. You can’t make one without the other, but they are not the same thing.

The schedule specifies what needs to be done, who will do it and when. And in the budget – how much it will all cost and what the whole project will cost.

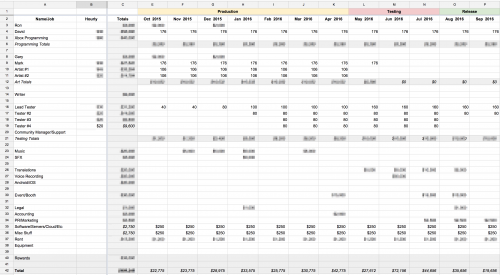

Below is the current budget of the game Thimbleweed Park. I call this a “live” budget. The columns in it start from October, and not from the start date of the project. The money that has already been spent is already in the past, it is only of historical or educational value. I want to focus on what we have left and how much more we will spend in the future.

Budget Thimbleweed Park. The picture increases on click

Anyone who understands accounting probably has an eye twitching right now. Surely you can arrange it all in some more sane way. But I’m not an accountant, just like most of the “indics”. So this simplified way of keeping a budget is quite suitable for me.

Every month I estimate how much we have spent compared to how much we should have spent, and based on this I make adjustments. Then I delete the column of the current month, look at the expected total and at the real bank account. If there is more in the bank than we plan to spend, then everything is OK with us, we continue to work.

Let’s go through the budget.

Employees come first. Gary and I work for nuts (in honey). Seriously, neither he nor I can afford to plow for 18 months for nothing. Of course, we earn a quarter of what we could at a “normal job”, but we still need to pay for food and a roof over our heads.

Everyone else also gets less than what they could. But they still need to be paid. I believe that if someone works for you “for nothing”, then the project (and your friendship) will have an unhappy end. In fact, if a person works for you for free, then you are not on his list of priorities. He will tell you that this is not the case. He himself, maybe, wants it to be different. But it is. And it all ends with broken deadlines and hastily made projects.

It is important that you have professionals in your team – to whom you will pay as professionals. Respect your employees’ time and their talent – pay them for their work. After all, that’s what you were raising money for on Kickstarter for.

The budget includes a five-day working week with an 8-hour working day. We try to stick to a normal schedule. There is no doubt that by the end of the project, the number of working hours will begin to increase. But at the stage of budget planning, I try not to put crunches in it, because this is a dangerous practice. We will deal with costs in the future – and then either we will hire someone new, or we will pay for additional time ourselves, or we will redistribute resources or cut content. There will be some holes in the budget to cover some of these expenses. But I don’t intend to write it all down in advance, because then the crunch will become a reality.

We are budgeting to hire two additional artists. It is not yet known if we will need them, but I have written them down – just in case. We may need help with animation, and there are also a bunch of all sorts of close-ups (phones, control panels, information boards) and other little things that Mark doesn’t have yet [Mark Ferrari, the artist of the project, – approx. editors] in the schedule.

There is a line in the budget for an additional screenwriter. We decided that we would have dialogues in the style of Monkey Island, and I am not sure that I will be able to devote time to this, considering how much I still have to do (including the budget).

Testers, testers, testers. One of the most needed and often undeservedly forgotten positions in the project. This is money wisely spent, because if you save on testers, then urgent patches, disgruntled players and malicious reviews will cost you a pretty penny. At first I budgeted three testers, but then I added a fourth one after we decided to release on Xbox as well. I will spend more on testers than originally planned, so here, maybe, it will be possible to fit into the real budget (in the comments already, I feel, they have prepared rotten tomatoes).

It is important to understand the difference between a test and a beta test, as they serve two completely different purposes. The task of testers (mostly) is to look for and help get rid of bugs. They pay for it because testing the game is very tedious. Plus, to be honest, few people cope with this normally. Testers aren’t just playing a game. They’re testing it. This often means that you have to replay the same five minutes over and over again to catch the same elusive bug. Testers should be able to write clear and understandable descriptions of bugs, and then track them a hundred times to understand whether an error has been fixed or not. It’s hard work. A good tester is worth every penny spent on it.

A completely different story is the beta test. Beta testers (in an unpaid position) are also looking for bugs, but in fact they are needed to track larger shoals – whether the puzzles in the game are complicated, whether the game flow is interrupted, whether the player understands the story as a whole. Beta testers play the game almost like regular players and give feedback. You take fifty beta testers, launch them into the game and see where they go.

Then we have music and special effects. Musicians are usually paid per minute of the soundtrack. So if you want 15 minutes of unique music that costs $ 1 thousand per minute (a common price), then budget $ 15 thousand. A thousand dollars per minute includes, among other things, the search for a suitable soundtrack, changes, mixing and corrections. If you want free music, then ask yourself if you are ready to spend weeks studying different styles, trends and musical trends, selecting the right music, then months for mixing and, finally, months more for small additions, changes and corrections. And all this in order to end up with 3, 4 or 5 perfect mixes. This is a lot of work – and at the same time you will need to fit into deadline after deadline. And this is all for the sake of a relatively low-budget project.

The next items are translation, voiceover and mobile. Here I decided to rely on chance to some extent. I have no idea how much they will cost me, so I just laid the maximum cost on them. I expect that it is here that surpluses will be formed, which will cover the remaining holes in the budget. I thought like this: I looked at the prices for voice acting and translation, and then I added 30%. About iOS and Android, I have no ideas at all. I just took a large sum out of my head. Here it is, budget voodoo! If I had a producer, he would have calculated everything exactly. And I just added as much as I saw fit.

Now to the events. We will most likely want to show the game at PAX, Indiecade, E3 and similar events. This, in fact, refers more to PR and marketing. From this point of expenditure, we will take additional money if it turns out that we do not fit into the budget. If the game is not shown, it can harm it in the long run, but it is much worse – not to finish it at all. Plus, we can increase and decrease the numbers at this point when we have a clearer idea of how things are really going.

Then we have exciting items: copyrights, accounting, software and, of course, the most important line – all sorts of stuff. If we are not sued by this point, then these are all very predictable and fixed costs. But you can’t forget about them either.

And finally, rewards on Kickstarter. We have a fixed amount set aside for them. We calculated it based on how many people invested in our project. There is most likely 25 percent more than necessary. But this is good, because this way we have a certain room for maneuver. We can make the packaging more attractive, we can invest money in the project. Well, or we just made a mistake somewhere and counted incorrectly.

At the very bottom we have the total. I check with him every month, then I look at the Banskov account. So far, everything is fine with us. But that’s just because I worry about it all the time.

There is not one item in the table that I have shown here – this is the money that comes from the Humble Bundle and from new backers. There are not huge amounts, but not quite a trifle. I did not include them in the budget, because they will give us the opportunity to correct small errors, if anything.

We have several approximate goals planned for the next few months. They are not in the budget, because if we do not achieve these goals, they will not cost us anything. If we achieve it, we will change the figures adjusted for these goals.

We may also rearrange the frames somewhere, spend a little less on artists and hire another programmer. Budgets in general are constantly updated in the process of work.

The moment that is sure to raise someone’s questions is the level of our monthly spending. We spend a lot of money every month. By themselves, all the items of expenditure are quite modest, but if you add them up, it turns out unexpectedly a lot. We have a fairly budget (but not a trash) game, and it still costs us $ 20-30 thousand a month. That’s why I’m skeptical about Kickstarter projects that ask for very little money, and the team list is three sheets long.

I hope that the text turned out to be informative. There are a lot of ways to budget, and I’m more than sure that there are more correct approaches than mine. But this particular one has never let me down.

Please respect what we share with you. We publish all this amount of information not only to make it clear where the money is going, but also to share our experience. That’s how games are made. They take a lot of time, a lot of money, and it’s also a very confusing process.

A source: http://blog.thimbleweedpark.com

Other materials on the topic: