5 Trends and Tricks Related to "hard currency" in Mobile free-to-play games

Wolfgang Graebner analyzed the game currency in 32 games and found out a lot of interesting things. You can find out exactly what it is by reading the Russian version of his material.

Most mobile shareware games sell hard currency (aka premium): gems in Clash of Clans, donuts in Simpsons Tapped Out, gold in Game of War and so on. I spent some time analyzing exactly how hard currency is sold in 32 games from the App Store, and discovered some interesting trends and tricks.

Games

What kind of games?

I must say right away, I did not choose the games in a scientific way. It's just a mix of what I played, wanted to play, or what I found in the box office top.

The full list looks like this:

8 Ball Pool, Angry Birds Go!, Boom Beach, CastleVille Legends, Clash of Clans, Clumsy Ninja, CSR Racing, Disco Zoo, Dungeon Keeper, Empire, Farm Heroes Saga, Game of War, Hay Day, Hobbit: KoM, Jelly Splash, Juice Cubes, Kingdoms at War, Kingdoms of Camelot, Knights & Dragons, Modern War, Monster World, Moshi Monsters Village, Papa Pear Saga, Pocket Village, Puzzle & Dragons, Real Racing, Royal Revolt 2, Samurai Siege, Simpsons Tapped Out, Smurf's Village, Subway Surfers, Top Eleven.

Here you can find all the data I have collected (carefully, excel).

Trends and tricks

1. There is not much difference in pricing

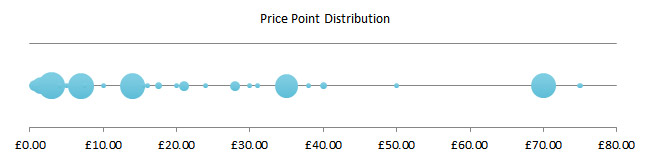

This chart speaks best about this:

Many games offer the following five prices: £2.99, £6.99, £13.99, £34.99 and £69.99 (or $4.99, $9.99, $19.99, $49.99, $99.99 in dollars). The big bubbles on the chart are these numbers.

The most popular solution is to offer users these five positions without any changes. So, for example, did the authors of Boom Beach!

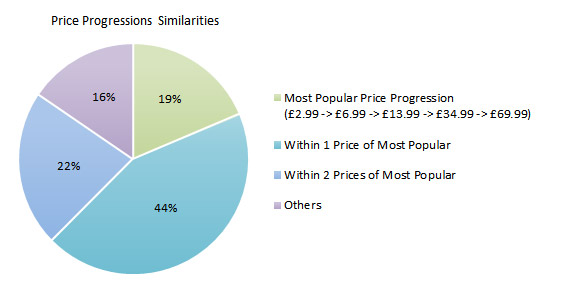

I found a similar price segmentation in 19% of the games. At first glance, it may seem that this is quite a bit, but in fact everything is as follows: in 44% of cases, this segmentation is changed by one point (either another price tag is added, or it is removed, or it is changed). In 22% of cases, not one price tag is modified in any way, but two. Only 16% of the games used a completely different pricing model.

Among those who chose the most unique price tags are Moshi Monsters Village and Empire. Both projects have four changes compared to the standard price segmentation. It's nice that someone is trying something a little different from the standard. The question is, will their approach become popular?

2. Players want cheaper, publishers don't

What should be the minimum price tag? Everyone has their own point of view

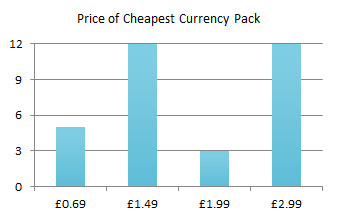

The price of the cheapest package

I wanted to know: is it worth making a minimum price tag below £2.99?

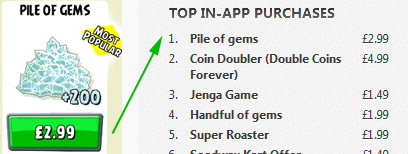

The top most popular App Store purchases show very interesting things:

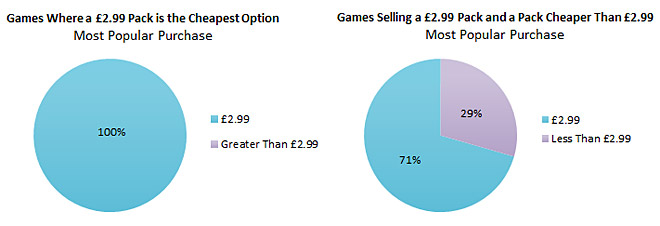

- In 100% of cases, where £2.99 is the minimum price tag, it is also the most popular purchase;

- 17 games had a minimum price tag, below £2.99, as well as a price tag of £2.99;

- For the majority (70%) of these 17 games, the £2.99 price tag is still the most popular.

The same information is in the diagrams:

This suggests that even if you offer players a minimum price tag below £2.99, they may prefer to buy something for £2.99. However, some questions still remain:

- When the minimum price tag is £2.99, how many sales are lost from those players who don't want to spend that amount?

- How much money was received from players who would have preferred to buy hard currency at a different price, but were forced to spend £2.99 because it was the minimum price tag?

- And more importantly, which amount is greater: the first or the second?

Unfortunately, I don't have enough data to answer this question. But it seems to me that the statement of David Edery from Spry Fox at the last GDC was true. He, in turn, said the following: "You'd be surprised how many people who wanted to pay a dollar for something are also willing to pay five dollars." This was how he expressed regret that he had put up too low price tags in his game.

If it were me, I would probably put £2.99 as the minimum price tag and, if suddenly needed, then I would introduce a special starter package at a lower price. It is always easier to reduce the cost than to increase it.

3. A lot does not mean cheap

I assumed that the more currency I buy, the cheaper it costs me (more on this here). But this is not always the case. The best example is Angry Birds Go:

Spending 2.5 times more, you only get 2.1 times more gems. If you want 2500 gems, you can save money by purchasing 2 packs of 1200 gems and one pack for 100 gems. It will cost you £29.97, and you will save £5 compared to the amount you would spend if you bought 2,500 gems at once.

And this is far from an isolated case. This practice is used in 70% of the games I have studied.

Sometimes this happens in the American store:

Sometimes it seems to me that it's all about price localization. When something is priced at $4.99 in the US store, it is usually sold in the UK for £2.99. But for some reason, $9.99 sometimes turns out to be £6.99, although it should be £5.99. Hay Day is a good example of this:

I am not sure how or why this practice arose, but I do not know that this problem has been solved in any game. So sometimes you get less hard currency for one pound than for one dollar.

4. "Most popular" is not necessarily the most popular

As a player, don't believe everything the publisher tells you. Only in one of the eight games advertising the "most popular deal" was such a price choice really the most popular.

Angry Birds Go turned out to be the only game in which the "most popular purchase" tag was actually the most popular:

Does this mean that everyone else was lying? I suppose that in some other region or maybe in another time, the tag was valid, but in my case most of them are outdated.

In any case, it is in the interests of the developers themselves to correct this, because in all other cases (cases of hoaxes) the most popular deal was minimal. And in whose interests is it for users to purchase cheap packages? Certainly not in the interests of developers and publishers.

5. Another way to calculate the bonus

In some games, developers like to tell players how much more profitable a particular purchase is.

The first example is from Kabam's The Hobbit.

- The minimum amount of gems received for £1 is a pack for £6.99. 100 / 6.99 = 14.3 hard currency for each £1;

- Based on this course, for £13.99 you should have received 13.99 x 14.3 = 200 gems;

- But the developers gave 240 gems for £13.99, not 200;

- 240 / 200 = 1.2. In other words, you got 120%, that is, 20% more than you should have.

I mean, everything seems to be fine. And 20% sounds great, and it doesn't go against the truth. The problem is that not everyone thinks that way.

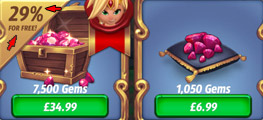

Here's a different example for you, this time from Royal Revolt 2.

- As in The Hobbit, the starting point was a pack for £6.99.

- Starting from it, for £34.99 you should have received 5,256 gems, not 7,500.

- And that's where the differences from "The Hobbit" begin.

- The developers put 7,500 — 5,256 = 2,244 gems on top.

- 2,244 / 7,500 = 0.299, so we can say that out of 7,500 gems you got 29% for free.

But, look, first of all, they could just round that number up to 30%. Secondly, if they followed the Kabam method, they could honestly say that they are making a discount in 43% (7,500 / 5,256 = 1.43).

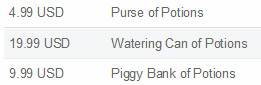

Another interesting example is from the game Monster World.

If you try to calculate the discount using any of the mentioned methods, you will not succeed. However, if you convert it into dollars, then the situation will be formed.

In dollars, the bonus in Monster World counts the same as in The Hobbit. So, apparently, it's all about localization. The prices were changed, but the bonus was not recalculated again. And, in general, bonuses in pounds are not so impressive (7% UK vs 25% US for 100 potions and 70% UK vs 100% US for 4,000 potions).

The original can be found at the link.