Zachtronics'Eliza: How to take control away from players and get away with it

Open worlds. Glossy visuals. Branching narratives that players can take wherever they want. Games have never been in a better shape to create believable experiences. At least, as far as AAA titles go.

Indies, of course, can rarely afford the whole package.

But sometimes they don’t need to.

Eliza is a visual novel exploring the faltering world of human connections in an increasingly digital reality. Even for a visual novel, there is not a lot of interactivity. In fact, throughout much of the game, all you can do is just click on things. Not that it would matter in any significant way.

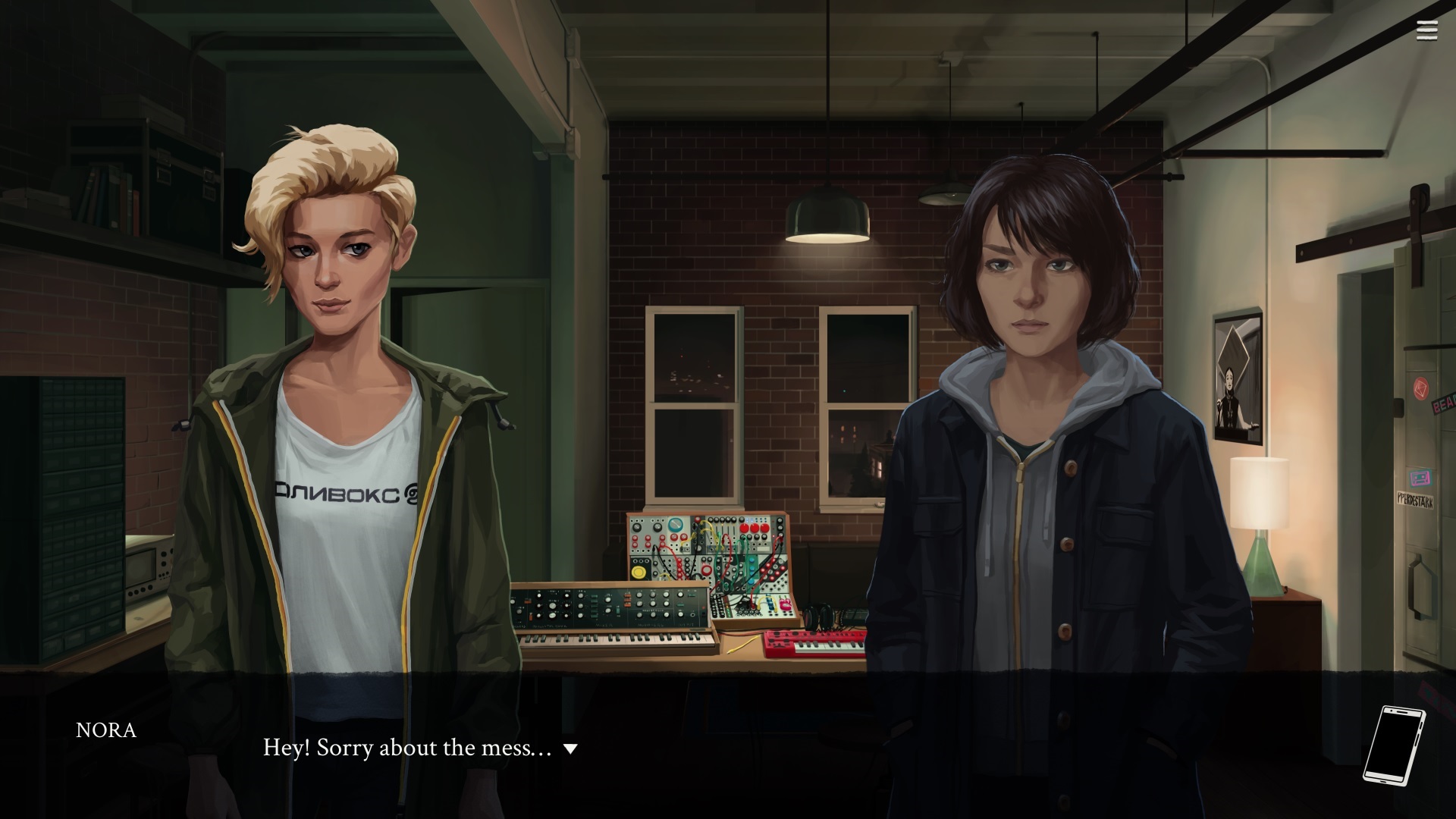

Instances of exploratory clicking alternate with dialogue scenes that will have you choose from only a couple of options. And then there are therapy sessions when you just click through a series of answers generated by the eponymous “Eliza” AI counseling system. Zero options here. It’s restrictive to the point that the protagonist, Evelyn, notices that.

No, the game doesn’t break the fourth wall with this. The protagonist does not actually comment on the gameplay. She does, however, notice how the in-game world fails to offer any meaningful choice in her interactions with other people. I hear you, sister! I know I was, as a player, frustrated with how limited and inconsequential my choices are.

And that’s, surprisingly, where the game becomes uncomfortably life-like.

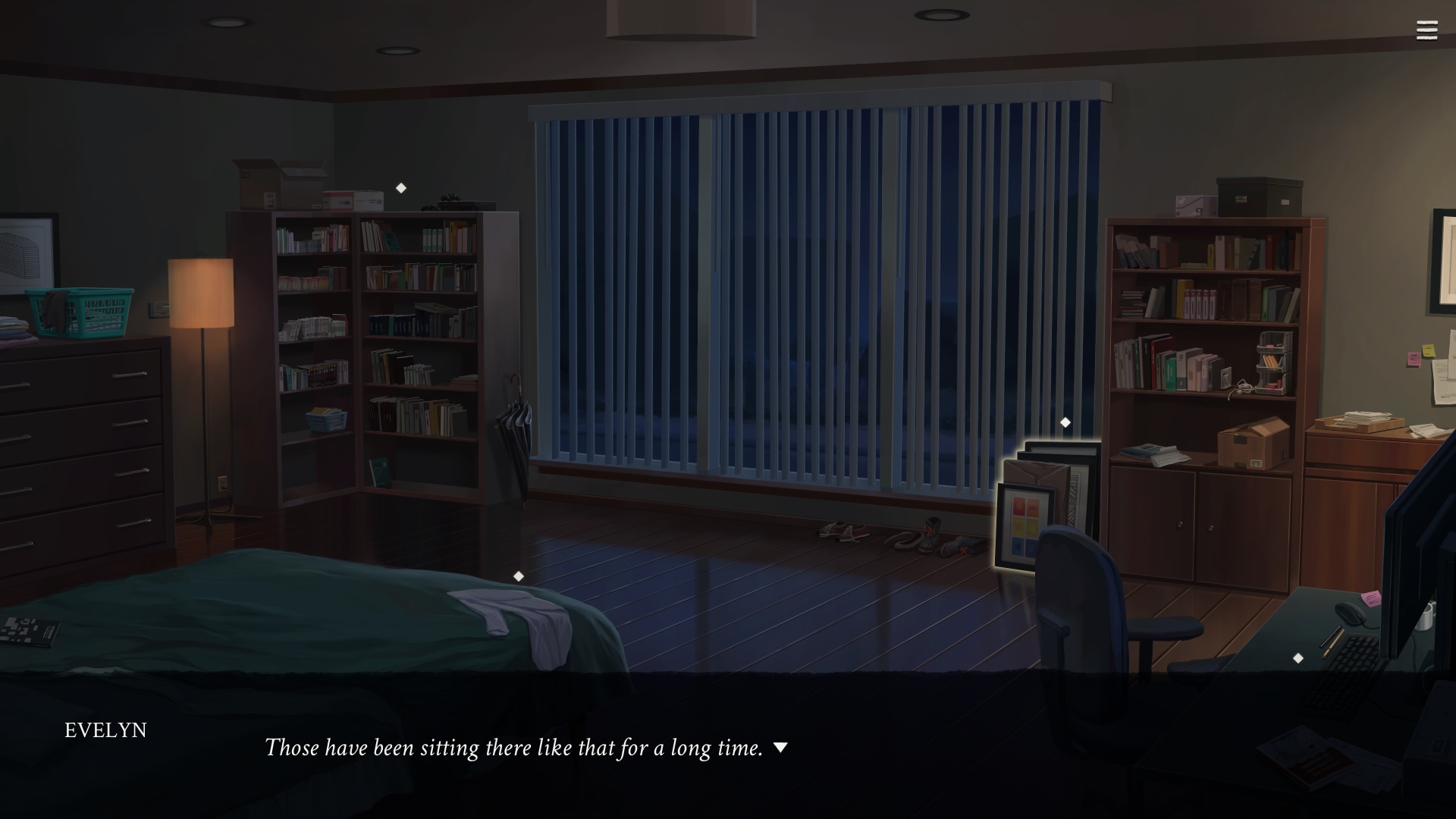

There is a scene when Evelyn comes home. Time to immerse yourself in the pointing and clicking extravaganza. You click on some paintings that Evelyn has been meaning to put up for some time. Click all you want, she’s not gonna do it. She’ll just wonder whatever it is she’s been waiting for. Or you can click on the book shelves that she’s been wanting to tidy up, but again, maybe some other time. Or the clothes. Will Evelyn put them away? No. Why bother. After all, she’s been wearing the same clothes since college.

It’s like Evelyn lives in my place. We are even the same age. 34. I, too, have stuff that I have been meaning to relocate but still haven’t worked up the nerve. Look at this stack of T-shirts sitting on the armchair. If I were a protagonist of a game, I would not be too much fun to play as.

Once you put yourself in Evelyn’s millennial midlife crisis shoes (that is, if you are not already there), the bareness of the choice-less gameplay starts to really make sense. It’s all about not making any sudden moves. It’s about hardly knowing what to do next. And sometimes it’s just about wanting to “lie down… forever.” That’s actual Evelyn’s words.

Now I would have totally understood if from there the game had proceeded to become a sleeping simulator.

Fortunately, Evelyn reaches a point when she is capable of shaking off that familiar paralysis of will. And that’s immediately reflected in the gameplay.

Remember how you didn’t have any say in anything at first? Well, get ready for a dialogue sequence that will make you choose from up to 16 (!) options. It’s not exactly the Garden of Forking Paths type of situation, but that’s definitely more control than before.

Cleverly, even in this later portion of the game, Eliza will remind you that the real life can sometimes feel “scripted” no matter what you do. There is this old lady that, whatever you tell her, will just go on rambling about what’s on her mind. And you can’t possibly get out of this conversation or stop it. Frankly, the nonresponsiveness of this character made it feel like one of the most life-like exchanges I’ve had in games.

Bottom line: Eliza is quite brilliant. Not just in terms of voice acting, stylish visuals, or storyline. It takes the interactivity away from the player, and once they no longer take it for granted, once they deserve it and are actually in the position to do something with it, the game finally allows the player to matter.