What is narrative weight and how game designers can manipulate it to add value to certain elements

Why do players consider some events and details in the game more significant than others? This is directly related to the so-called narrative weight. Andrei Medvedev, game designer at Friday’s Games, breaks down what this term means and why it is critical for game designers to be able to adjust the importance of certain elements.

Andrei Medvedev, game designer at Friday’s Games

What is the narrative weight?

Imagine a typical room description in a text-based RPG:

“As you enter the room, you see a wooden wardrobe, a wooly carpet, a window, a sofa, and a tea table. The carpet is decorated with a beautiful picture of a purple and yellow badger. On the right half of the carpet are two coffee stains.”

The designer thinks: “The only logical place to store the treasure is the wardrobe. Come in, loot the treasure, get out. Two minutes tops.”

But why do players spend two hours scrutinizing the carpet in every little detail and then take it with them? Because they probably think: “Well, why did the GM describe the carpet in such detail if it’s not important?”

This reaction can be explained by the more sophisticated term “narrative weight”. It is the amount of time and content devoted to an event or a detail in a game.

Usually, the greater the narrative weight of the event, the more significant it is to the players. This significance may or may not match its true importance in the narrative. That’s why the disparity between the element’s weight and its true significance causes dissonance and dissatisfaction.

In the example above, the narrative weight of the carpet was the highest in the room. This caught the attention of the players. But the significance didn’t match the intention. The designer just loves describing carpets.

So, it’s the designer’s task to match the narrative weight of events with their significance and players’ expectations. Lack of content and dedicated time decreases the weight.

What can increase it? Unique art, 3D models, music, unique sound effects, voiceover, unique dialogue, lore, unique mechanics, locations, cutscenes, the length of the cutscene, the length of combat, the time it takes to travel to a goal, and more.

Sometimes it’s literally just SIZE that helps. Big things draw attention and are usually quite significant. The massive golden tree in Elden Ring. The Reapers in Mass Effect. The Tower of the Swallow in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. World wonders in Gods and Glory. BFG in Doom.

How to measure the narrative weight?

You can’t really say that some events weigh 3 kilos, and some 5 tons. Narrative weight is always relative. The players compare the event to every other event in the game, as well as to their expectations. The expectations come from other games, media, and real life. Thus, we can say that some events are more significant than others, or that some events are relatively weighty in the context of the game.

Let’s take a look at some examples.

1. Mass Effect

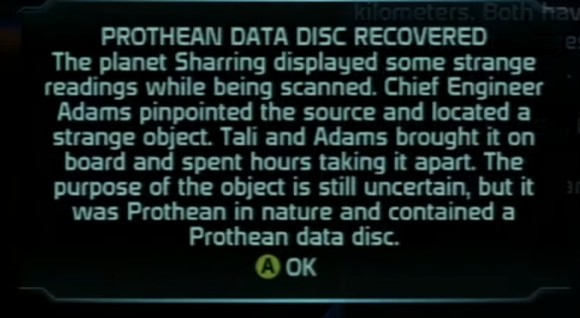

There are three long collection quests in the first Mass Effect. They all play out the same way: the player lands on a planet, finds an icon on the map, travels to it, interacts with some ruins, plays a hacking mini-game, and reads one or two sentences of pop-up text saying that the item was found.

So, the narrative weight of these quests is: a 3D model of the ruins, a hacking mini-game, a short description of the quest in the log and one or two sentences of description upon collection. I’m not counting the map icon, because it’s the same for everything.

It’s also worth noting that the model of the ruins is reused in all three quests. And the hacking mini game is extremely common everywhere. These reuses significantly decrease the weight in the players’ eyes.

There are no serious events in these quests, the characters can’t die or change, there is no dialogue or voiceover. The narrative weight of these quests is extremely low and they spike no interest.

There is, however, another collection quest. It begins after a dialogue with the Consort on the Citadel (the game’s hub). Upon completion of her quest, Consort gives the player an item that must be used on a specific ruin on one of the planets. After interacting with the ruins, a few paragraphs of text about ancient aliens guiding early humanity through the Stone Age pop up.

It’s mechanically the same collection quest. But its weight is much higher: a unique, voiced dialogue, an uncommon ruin model, an attached quest, an item in the inventory, and paragraphs of text (as opposed to only a few sentences).

Obviously, the quest stands out. When I played it, I immediately thought it was so big and significant that it would develop and play out more later. It didn’t and I was disappointed. But other collection quests didn’t even inspire such expectations.

So, the three collection quests set the standard narrative weight for these types of quests. When another quest of that type emerged and had a higher narrative weight, it’s significance was also higher for me, the player.

2. The Witcher 3

Let’s talk more about points of interest (POIs) here. The narrative weight of them in The Witcher 3 is much higher than in Mass Effect 1.

When the player comes to a treasure POI in The Witcher 3, they can expect an enemy and a fight. Then the player picks up an item from a glowing model — usually a corpse or some container. This can be a diary or a note with story content about the treasure. A quest pops up that guides the player to the treasure. Finally, in another 3D model lies the treasure: a few reused items (only sometimes uniquely named).

This standard is preserved throughout the whole game for almost all other POI types. When the standard is lower, like in the “Contraband”, which contains no lore or additional quests, players find them insignificant and boring. That’s why Skellige, where Contraband POIs are prevalent, is a borefest compared to other locations.

But in the Blood and Wine DLC, CD Projekt RED further increased the narrative weight of POIs by linking them to an general quest that progresses after clearing each point. The great examples are:

- The statue of Prophet Lebioda that is built up every time Geralt rescues workers at the point of interest;

- The mystery of the two winemakers that unravels each time Geralt helps clear points of interest in their fields.

POIs are one of the smallest encounters in RPGs and are often overlooked. Due to their high narrative weight, POIs in The Witcher 3 have become an industry standard for me. Now, when I see a random chest in a tough to reach place in Baldur’s Gate 3, I expect to find at least a note with a story about how it ended up there.

The high narrative weight of small events elevates them and the game as a whole in players’ eyes. The Witcher is famous for its depth, not least due to the high narrative weight of its smallest events.

3. Playrix games

You can study the narrative weight of events of any size. For example, the narrative weight of the Farmscapes DLC consisted of a 6-day story (each day ~30 quests, each quest ~4-7 lines of dialogue); one 2D location; one character (including 3D models and art); ~30 3D animations and so on. The players came to expect nothing less, because previous ‘Scapes titles set the standard.

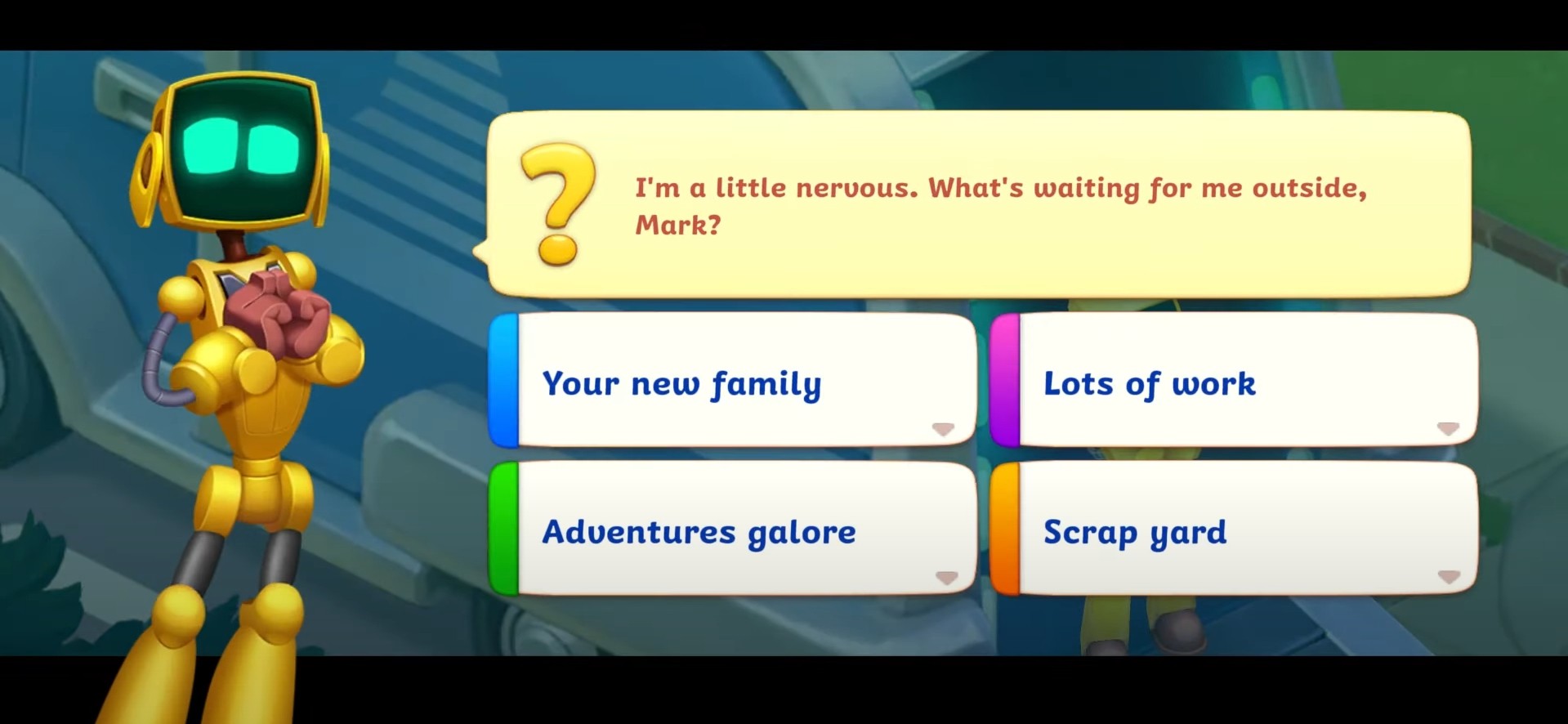

In Playrix’s new game Family Hero, the developers have also taken the path of increasing the narrative weight. For some quests, they added elements of Trivia and more.

High and low weight events

Game development is expensive, and every hour is precious. Game designers should first spend their time increasing the weight of significant events. What are those events, precisely?

Some events are naturally significant and therefore should be relatively heavy. You can find events that are common to all games, but they are usually specific to a certain genre:

- In RPGs (and other story-driven games), it’s the death of an ally, love events, completing a long-term quest, destroying or saving the world, plot twists, level ups, attaining legendary items, casting extremely powerful and rare spells, defeating a boss, talking your way out of a sticky situation.

Some players consider the journey to an encounter as important as the event. For this reason, there are players who refuse to fast travel. And we must add content for them along the road;

- In mobile games (typically), this can be getting a legendary item/character, the start of a new season, reaching level 1000 in puzzles, winning an alliance war/tournament, winning an event, or the event itself.

- In competitive shooters, this can be winning a match, a headshot through the wall, an ace, the release of a new season or a new map/mode, or the release of a new hero (for hero shooters).

- In strategy games, this can be using a new unit for the first time, a plot twist in a campaign, using a mega weapon (like the nuke or Odin in StarCraft), boss levels, or wars in 4x strategies.

Narrative weight in TTRPGs

Tabletop RPGs are essentially RPGs. So I usually borrow the approximate narrative weight from my favorite video game RPGs and roll with it in my D&D campaigns.

However, in TTRPGs a lot of content is up to the player’s imagination. How would a game designer increase/decrease the weight in such restrictions? There are a few tools:

- Time. The more game time you spend on an event, the more significant it looks. The campaign-end boss fight could take the whole session, maybe even two. Traveling through the famously dangerous mountains takes at least a couple of encounters. The death of a player character can take minutes. Obviously one should know when to stop, but time is a useful tool;

- Text. A long description can make an event stand out. As with time, know when to stop though;

- Maps and models. A unique 3D-printed model for a boss matches its significance. And if it’s a model of an NPC, the players freak out even more;

- Music. If you are using music constantly, players get used to generic battle/peaceful music. Hand-picked tracks can elevate an event in the player’s eyes;

- Unique mechanics. Experienced players notice them very well, especially if you just tell them directly. If your monsters have one action, give the boss two. Or three. (Legendary actions, anyone?). Or something even wilder.

- Handouts. An authentic letter, an amulet, a potion bottle. Physical props are extremely heavy in terms of narrative weight.

***

The bigger the weight, the bigger the significance for the player. For game designers, it is important to spend their time on extra features for significant events and leave features for the insignificant ones in the backlog.

To determine the weight of an event, you must compare it with other events in your game and other genre-defining games and media. Set a minimal weight for the event type and stick to it. After that, you’ll be able to manipulate the weight to increase/decrease event’s significance in the player’s eye.