Books: a work on game screenwriting was published in Russian. It's called "Kill the Dragon." We publish an excerpt

According to the Bombora publishing house, the work of Brighton Robert Denton Bryant and Giglio Keith (Keith Giglio) “Kill the dragon! How to write brilliant scripts for video games.” The book is positioned as a guide to the world of video games, which will help you understand how to write game scripts better.

CHAPTER 05 — Creating a Great Game Character

EVOLUTION OF VIDEO GAME CHARACTERS

There is a long tradition of creating video game heroes in the form of not too distant “jocks”, such as Duke Nukem, and they owe their existence to the popularity of action heroes of the 1980s in the style of “shoot first, ask questions later” performed by Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Chuck Norris. There were exceptions, such as Mario and Miss Pacman, but it seems that by default in many games the hero was a white man of the Reagan era.

This was partly due to the spirit of America at that time. In the 80s and early 90s, when video games appeared as media, most of the pop culture, seeking to get rid of disappointment after Vietnam and Watergate, was obsessed with tales of male power: Rambo films, “Missing Persons”, “Commando”, “Predator”, “Die Hard”. On TV — “Miami Police”. In the comics with the release of The Return of the Dark Knight, Batman was remade (or finally revealed) into an embittered sociopath. Marvel’s most popular superhero at the time, Wolverine, was a short, vicious sociopath from Canada. And let’s not even start about the Punisher.

Since the game developers either directly licensed these films, or created similar characters so that players could feel like a Rambo hero played by Sylvester Stallone (in Contra) or any hero played by Chuck Norris (in River City Rampage), the vast majority of the heroes seemed almost the same. The action took over the plot, and Duke Nyuk became the Steven Seagal of video games. (And Jean-Claude Van Damme became the Jean-Claude Van Damme of video games when he starred in the movie “Street Fighter”.) The character’s identity didn’t really matter. He had a gun. He had a purpose. He had his own audience. This hyper-macho approach in the style of “action first” was later ironically reflected in the movie franchise “The Expendables” by Stallone and in the game developer Free Lives.

In many American games, the main characters were often evil loners or super-skilled operatives, in whose roles players could jump, climb, fight and shoot, and then hear from their mouths a cool phrase, for example: “You know what, freak? Duke is getting down to business again, and the last thing that will flash through your head before you die… will be my size forty-six shoe!” (Duke Nukem 3D). At the same time, clearing the level was nothing special; a “day job” for a game character. The characters were people of action whose emotions ranged in a very narrow spectrum, from anger to cold cynicism—the very spectrum that is a tiny zone of emotional comfort for teenage boys.

In Japanese games of the same era, the main characters were very often real teenage boys: delighted with the fantastic situation they found themselves in, hot-tempered, reluctantly acknowledging the fact that the world requires them to take the next step and fulfill their destiny (for example, to grow up). A typical protagonist of Japanese games of that time (for example, Cloud Strife from Final Fantasy VII) was created as understandable as possible for the target audience — insecure teenage boys (and girls!).

If history is a path of emotions, then this path in early American games turned out to be very short.

Who is Tabula Rosa?

Another trend is common among game developers — to make their hero a “blank sheet” or a “blank board” (tabula rasa). One of the most hackneyed cliches in video games is the protagonist with amnesia and the following features:

• he is a blank slate on which players can portray their own emotions, and

• he does not know about his abilities in the game (like a player).

We believe that many players no longer need either the heroine “Tabula Rosa” or her brother “Tabula Ross”. Entering the role of a real character makes the game more emotionally intense. Screenwriters and playwrights are taught to show only the tip of the iceberg that the character represents. There’s a lot more under the surface of the water—something we’ll never see: the backstory. Quirks. Own point of view. Initially, the games were developed based on technology, and the background was not particularly taken into account. Mario is a plumber, and that’s it. Duke just likes to blow things up.

Think about the evolution of Mario — how deep could the characters be depicted in that low-tech environment compared to modern standards? Look at the Prince from Prince of Persia — in fact, it’s the same game, only on different platforms. We’ve come a long way from programmers writing dialogues for 16-bit two-dimensional characters. Jordan Mekner created the first “Prince of Persia” based on the game mechanics. Yes, the prince had a goal, but he didn’t have a special story arc. And why is she in such a small game?

Over the years, Mekner has moved from writing code for games to working on their plots. With the advent of three-dimensional graphics, he made the prince more three-dimensional. In modern versions of the game (starting with the 2003 game Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time) players play for the prince for hours without stopping. Naturally, they want the character to be interesting. I want to go through not only his path of action, but also his emotional path.

First-class talent requires first-class roles

We live in an era when game producers hire actors not only to voice the characters, but also to capture the movements that give realism to the characters. In LA Noire, the characters played by Aaron Staton (TV series “Mad Men”) and John Noble (“The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King”, the series “The Edge” and “Sleepy Hollow”) not only sound like Aaron Staton and John Noble, but also look and act like Aaron Staton and John Noble. Major talent search agencies, such as William Morris Endeavor and CAA, send offers to their clients-actors to star in games. Creative directors, screenwriters and game designers now don’t just create doll—like avatars that players move around the screen using a controller – they “write” real characters.

And this evolution is gradually leading to the recognition of video games as an art form. The British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA, the British equivalent of the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences) in 2002 began awarding the BAFTA Games Awards, awarding winners in such categories as “Best Game”, “Best Design” and “Best Game Innovation”. In 2005, the nomination “Best Screenplay” was added, later renamed “Best Story”. In 2011, the category “Best Digital Artist” was added.

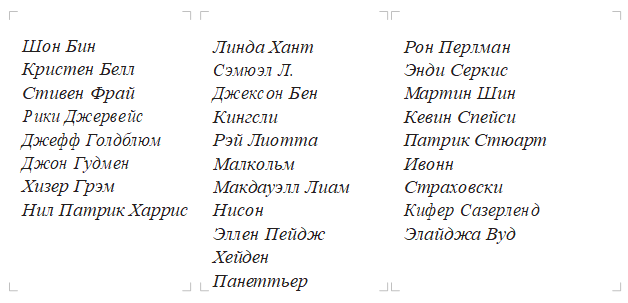

Here is just a small sample of first-class actors who have played in the games:

And this is only an incomplete list. Among them there are Oscar nominees and winners, Tony Award winners, stars of popular TV series and films, adored by critics and viewers. What attracts all these talented people? It’s not about the money or the fact that they demonstrate amazing skills (they can do it in the movies).

It’s about the characters. It always starts with the characters. Or not?

WRITING FROM THE STORY ARC

What is more important in the story — the plot or the characters? Probably, after all, the plot? Of course, this makes sense — no one wants to watch or play something boring. No one will like a story that “goes nowhere.” Think about it: the world, the action, the promise of exciting adventures — an advertising poster, a trailer on the huge screen of the E3 exhibition. All this is the cover of the game! But what about the characters? Brad Pitt, Reece Witherspoon, Denzel Washington — name almost any famous actor or actress, and they will say that they are attracted not just by a good story, but also by the prospect of getting used to difficult, conflicted characters.

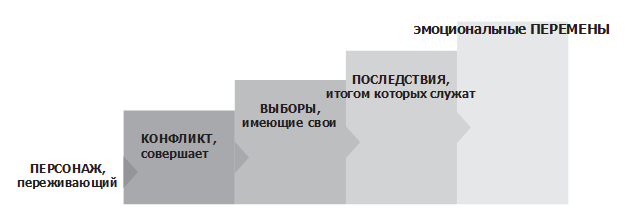

The main character in a good story must experience some kind of emotional transformation underlying the character’s story arc. The story is the path of emotions, and the game is the path of action. How to combine these two concepts and convey emotions so that the player does not just play the game, but experiences the emotions of the character? Keep an eye on our next chapter! But first we need to understand what makes a character good—in a game, a movie, or any other narrative.

In most stories, the main character changes during the unfolding of the plot. This requires a storyline (action) that affects the character’s line (emotions). In the storylines of fascinating games, movies or TV series, the shortcomings of the character and his struggle with his fears are shown, which leads to the development of events. If your story doesn’t force the character to change, then either the story is wrong or the character is wrong. The actions in the story affect the emotions in the story.

Don’t forget about the ending!

A good dramatic work is created “backwards”. For a story to have a strong emotional impact, a writer must know—for any narrative on any platform—what the ending will be! If you want to get somewhere, you need to know where to go. In order for the narrative to work, in order to deeply engage the player and the audience, the writer must know how the main character will change.

The writer! Never forget about the ending! If you don’t know where you’re going, how do you know where to start? Who is the main character at the beginning of the story? Who does he become in the end?

In the movie Titanic, Rose (played by Kate Winslet) turns from a closed, pampered rich child into an adventurous young woman who lives to the fullest.

In Avatar, Jake Sully (played by Sam Worthington) is an emotionally burned—out former Marine who by the end of the story becomes a passionate leader of the revolution. In the first Terminator, Sarah Connor (played by Linda Hamilton) turns from a naive waitress into a selfless defender of humanity. In the movie “Terminator 2: Judgment Day”, the Terminator turns from an insensitive machine into a kind of father and sacrifices himself for the sake of the people he has fallen in love with. Okay, these are all James Cameron characters. (We were on a roll.) Let’s look at the others. We suggest you analyze Shrek, Nemo’s father Marlin, Belle (and Sebastian), Ariel, Luke Skywalker, Han Solo and Michael Corleone.

Like all rules, the rule “all characters must change” has some exceptions. Indiana Jones and James Bond come to mind; their emotional path does not go beyond “I was a loner, but now I have a girlfriend /father/ some kind of assistant who will already be gone by the next picture.” Danny Ocean (George Clooney) and Rusty Ryan (Brad Pitt) don’t change much from one movie to the next in the Ocean’s Eleven franchise, and, to be honest, we don’t want them to change. (Although they have a wife and a girlfriend.)

So, if you want to write a great video game, create a character who embarks on a journey of change. The path of action should influence the path of emotions. But how do video games display changes in a player’s character?

What does Kratos have in common with Michael Corleone?

A good story needs a character who doesn’t just get stronger and more skilled over time. (With this in mind, almost all game characters are created. Players want to get new abilities, and then go through tests that test these abilities.) We need a character who is also emotionally transformed. One of the most iconic characters in the history of American pop culture is Michael Corleone (played by Al Pacino) in the movie “The Godfather”. We meet Michael during his sister’s wedding. He tells his girlfriend Kay (Dai an Keaton) that he doesn’t look at all like his family, belonging to a criminal family. In the first God of War game, Kratos is also a kind of hero. He is a warrior, bound to serve the Greek gods. What does the world of Ancient Greece have in common with the mafia world of New York after World War II?

Both characters are antiheroes. They don’t go on a typical hero’s journey. They face internal conflicts. They both hate what they eventually came to.

Michael doesn’t want to be the godfather. His desire (like his father’s) was to lead his family away from a criminal lifestyle and learn to comply with US laws. Kratos wants to commit suicide. He wants to be free from the need to constantly fight and the guilt of what he was tricked into doing. (SPOILER: He killed his own family.)

Both of them begin to despise themselves. Both characters are built based on their purpose, but at the same time develop in the opposite direction. The writers “built” the ending into the characters. Each of them has its own story arc. Michael doesn’t want to imitate his father, but eventually becomes like him. Kratos wants to kill Ares, but takes Ares’ place as the “God of War”. A story in which a mafia son wants to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a big boss is not the most successful story. It meets our expectations; good stories challenge our expectations. That’s why Michael’s older brother Sonny (James Caan) is not the main character of the film. The protagonist in the course of the plot must overcome as much emotional distance as possible. The arch of the main character should be long.

We believe that games get better if strong protagonists appear in them and character arcs are carefully built. We like to express the idea of an arch in one sentence. You can call it a formula. Or a cheat sheet. Or “5 character factors”.

When developing your main character or choosing a main character, give him vitality with the help of these five factors. We don’t want to play just for an ordinary thimble or shoe (Monopoly chips). We want to know who this thimble really is. What are his hopes and dreams? What was his most severe childhood trauma?

Let’s start with character research. Who do I become during this game? Why am I here? What do I want? What do I need? This is one of the sides of the “Pyramid-grid”.

Characters

It is advisable to create characters who have to go the greatest emotional distance in the plot. Alfred Hitchcock, the master of suspense, had his own formula for creating a tense thriller. Time after time, he made films about ordinary people in unusual situations. The character must contrast with the background of the world in which your game takes place and face the harshest possible challenges. Remember the quote from the “Confiscator”. Your task is to get your character into tense situations. And more often.

The game Dead Space, which became a bestseller and marked the beginning of an entire franchise, was created under the great influence of the film “Alien”. It tells the story of Isaac Clarke, a “systems engineer” (repairman) who must use his skills to make weapons and survive after being attacked by monstrous space zombies on his ship. Isaac is not a warrior. Not a military genius. He is an ordinary guy who has to survive thanks to ingenuity. He is the most likely candidate to die first, but he survives.

The main character of the Assassin’s Creed game Desmond Miles is a bartender who is forced by the multinational conglomerate Abstergo Industries to interact with the “Animus” (a time machine for consciousness) and travel into the genetic memories of his ancestors. Yes, it’s interesting. But imagine if Desmond was a spy, a hired killer, or any other killer who would have to go into his memories. In our opinion, there would be nothing special about it. Such a scenario would meet our expectations. But a bartender who has to learn to be a killer? Quite an unusual activity. But the more interesting the plot.

In the game Infamous, Cole McGrath is a courier who has superpowers. In Brütal Legend, Eddie Riggs is a touring mechanic who has to go to hell and come back. In BioShock, you play as Jack, a Hitchcockian everyman. Andrew Ryan thinks you were sent to kill him, so he’s trying to kill you first. Alan Wake is a confused writer in the Alan Wake game of the same name.

In the game Telltale Games The Walking Dead, Lee Everett is an ordinary college professor, and he does not specialize in destroying zombies at all — it would be too easy. In the new world of the walking dead, his former profession is useless. Why? Because it’s more dramatic!

The meeting of the ordinary and the unusual

“The Lord of the Rings” should be considered not only as a predecessor of “Dungeons & Dragons” (Dungeons & Dragons). It is also an example of a narrative about a typical philistine who finds himself in an unusual situation. In the world of orcs, dwarves, elves, wizards, talking trees and eagles the size of a Greyhound bus, the bravest and leading a dangerous journey character is a humble, house—loving hobbit, that is, the character most similar to us.

The player strives for such empathy, and the narrator should strive for it in any environment. Hollywood experts call it comparability.

“What if this had happened to me?” the audience in the cinema thinks.

“This is really happening to me!” the players think. Most of all, we empathize with characters who, like us, are not perfect. The more flaws a person has, the more human we recognize him, the more we like him. If you want the characters to be more “realistic”, make them screw up in something. Endow them with fears and prejudices. Make them flawed.

WHO’S COOLER, SUPERMAN OR BATMAN?

Who is cooler: Superman or Batman? Try to compare them and answer. Take your time, think carefully. Not who is the “more powerful”, but who is the more convincing character? More interesting. Who has a more pronounced emotional message underlying each of his decisions?

Of course, this is Batman.

Why? Because he is a human being, and we can relate ourselves to him. Superman is a very gifted alien, he has always been superhuman, always stood above us mere mortals. Another feature prevents Superman from becoming a great character: he has no flaws, except that he is a little harsh. He’s a boy scout from outer space. (Batman, meanwhile, is a gloomy and obsessive inhabitant of Gotham City.) Superman doesn’t suffer. He always does the right thing. Mom and dad Kents brought him up very well, and in each version, Superman is told as a child that he was on Earth for a reason. When Superman first appeared in the comics, there was no kryptonite in them; it was added many years later in radio broadcasts when the writers realized that Superman had no weak points. Without weaknesses, there was no chance to die, there was no chance to fail, which means there was no drama. The “Precriptonite” Superman could not get into a tense situation. Readers, listeners and viewers (and he himself) always knew that he would win.

Batman is a human, mortal. Batman can suffer. And we understand that. Even if he has a lot of cool gadgets and is in much better shape than us, whenever he gets hit, we flinch. Not so with Superman. (Does he feel pain at all?)

Batman also has emotional problems, and he doesn’t hide them. His parents were killed, and he grew up alone under the guidance of an elderly Briton, Alfred, in a Gothic mansion. Such an injury can really ruin your life. Superman’s parents were also killed, but he did not witness this incident. He grew up in Kansas in a loving family with two foster parents, the Kents, who waited until Clark was a teenager to tell him about adoption.

Superman is the quintessence of a good citizen, he is both the president of the student council and a church acolyte. He’s like that kid at school with whom Mom always compared you not in your favor.

Batman is not like that. In a way, he’s even a psychopath. He is still overcoming his childhood trauma. And we, as viewers and readers, hope that he will always do this.

Also — importantly — Superman is inherently passive, and Batman is inherently active. Superman didn’t choose the path to Earth; he was sent here by his father. He didn’t choose to be raised by the Kents; they found him and brought him up in the spirit of their all-American values of the Midwest. Very little of what makes a classic Superman a Superman is based on his own choices. (Even the design of his costume was designed by Mom Kent!)

Batman created his own personality himself. He decided to devote himself to the fight against crime, he chose a long-term regime of brutal physical training and mind-blowing scientific research. He puts himself at deadly risk every night, patrolling the streets of Gotham and trying to rid the city of criminals. (Yes, he had an advantage—he inherited a fortune from his murdered parents. However, in seven decades of the Batman myth, Bruce Wayne has never hinted that his wealth was worth the price he paid for it.)

Successful characters have flaws. This means that good (in the sense of “well-created”) characters resemble us. Remember the main characters of “Seinfeld”, “Dexter”, “Stay Alive”, “Disappeared”, “Breaking Bad”, “Obvious”, “Iron Man”, “Spider-Man”, “Citizen Kane” — all these characters have serious flaws.

Let’s look further into the past: Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, Romeo, Juliet. All memorable characters of literature and drama. Those whose posters and images hang on the walls. Those who are recorded on our collective hard drives. In all senses — both good and bad — they are not quite right in the head.

It is more interesting for us to observe how imperfect people doubt, worry, rush about, than for perfect execution on the part of perfect people. We relate ourselves to mistakes, blunders, misunderstandings, vanity (or any other of the seven deadly sins). We perceive ourselves as people who “screw up”. (When you have a couple of free days, look for the word fail on YouTube.) We identify with losers much more often than with winners.

People are not omniscient, we are all insecure, fearful, imperfect. We like to watch characters with similar self-doubt struggle and overcome obstacles. This helps us to find hope that there will be something good in our imperfect life.

So where do these disadvantages come from?

conflict: THE ESSENCE OF THE DRAMA

One of the best starting points for developing an imperfect character is developing an internal conflict. Internal conflict arises from an emotional dilemma, from the confrontation of desires and needs. What the character wants doesn’t fit in with what he needs to do. The characters will have to deal with external conflicts later, throughout your story. This part of the game is the path of action. External conflict is everything that gets in the way of a character when he tries to achieve his goals. Hordes of Geth, green pigs, a bunch of Corpses, giant spiders, falling bridges, puzzles — all these are external conflicts, and they are easy to create. The trick is to create an internal conflict for your hero. That’s what makes it interesting.

Luke Skywalker wants to become a space pilot. He needs to stop saying, “I’ll never…” and “I can’t.”

Jack from BioShock wants to escape from Rapture. He needs to learn how to make his own choices, which fits perfectly with the theme of mind control sounding in this story, “Be so kind.”

Jack in The Last of Us wants to be left alone. He needs to learn to be a parent again.

The inhabitant of the Shelter, the hero of the Fallout 3 game, wants to find his father, but he needs to learn how to survive on his own outside the spoiled society of shelter No. 101. He has to grow up in a post-apocalyptic world.

BACKGROUND: HOW IS FINDING NEMO SIMILAR TO THE LAST OF US?

The internal conflict may also concern the character’s background. The character may be haunted by something that happened to him in the past. In cinema, in literature and in the theater, a technique has been used countless times when the personality of a character is formed under the influence of an event. The backstory is a “ghost” that haunts our hero and helps explain why he has flaws. In the Batman stories, the ghost of the past is the scene of the murder of Bruce Wayne’s parents, which we return to again and again. In Hamlet, the ghost is the real ghost of Hamlet’s father.

There is no one true and correct way to show this “ghost”, but almost always it is some kind of traumatic loss or failure. The ghost can be shown at the very beginning of the story (again, see “Hamlet”), in the second act, in scenes of memories (every second of the films you have watched), or else it can only be hinted at, but never shown directly (see “Chinatown”). Hitchcock’s film Vertigo opens with the fact that Scotty (played by Jimmy Stewart) cannot save a policeman from death. In the movie “Jaws”, it is only at the end of the second act that we learn that Quint (played by Robert Shaw) has a deadly fear of sharks, which arose after one very unsuccessful day in the navy.

By the way, about the marine theme: in the movie “In search of Nemo” we see how Nemo’s father Marlin (voiced by Albert Brooks) loses his wife Coral and hundreds of their fertilized eggs due to a barracuda. At the end of this sad story, Marlin discovers that he has only one egg left: Nemo’s egg. Marlin promises his unborn son that he will never let anything bad happen to him.

Plot-oriented video games also use “ghosts” as a backstory. We’ve already mentioned God of War: In the middle of the game, we find out that Kratos killed his own family. In The Last of Us, the game opens with a combination of narration and cutscenes, which can be called a prequel. First we see Joel’s caring father, and then the whole world plunges into madness because of a mutated strain of the cordyceps fungus, and Joel’s daughter, Sarah, is killed in front of his eyes. (Have you noticed a pattern here? Murders in front of witnesses — few things could be more traumatic.) Then the plot shifts to a few years later, where the ghost of that fateful day influences every decision of Joel, the game character. The end of the plot of the game is laid already in these first few moments.

Jack (BioShock), Geralt (The Witcher) and Samantha Greenbriar (Gone Home) are all characters with a heavy backstory played out in the game narrative. At the very beginning of the game, on the plane, Jack (that is, you) looks at family photos. They come back to you throughout the game. As the story progresses, you will gradually learn your shocking backstory: you are the illegitimate son of the man who now wants to kill you — Andrew Ryan.

Booker DeWitt (BioShock Infinite) is an emotionally traumatized, disgraced detective. Does his background play a role? Not the slightest doubt. In Red Dead Redemption, you play as John Marston, a former bandit whose backstory led to him being recruited to complete a mission (the beginning of the main storyline). In short, John has to kill members of his old gang to save his family.

Of course, exceptions are very common. They are in any media. There is no one right way to do something. (And with a good game design, it’s better if the player is given more than one way to solve the problem.) Not all characters change. Sometimes external circumstances change, but the characters can be clearly defined and remain so throughout the series. In the Uncharted series of games, Nathan Drake doesn’t change much. He doesn’t have a deep emotional wound, nor does Indiana Jones, and it seems to have worked out perfectly for both of them. In most police series, the emotional path of the main characters is not particularly great.

But over the course of a season or a whole series, they still develop, often against their will. (For example, Lieutenant Sipowitz played by Dennis Franz in the TV series “NYPD”.)

DON’T TELL BOWSER: THE BAD GUYS THINK IT’S THEIR GAME

When we think of some of the greatest, most memorable and dynamic characters, we don’t always mean the main character. In the story of Adam and Eve, there is a Snake — the most interesting character (because he brings … conflict to the story! And at the same time, sin and the fall of man, which is also somehow not very pleasant, but certainly dramatic). After that, Cain comes to the fore. Then God himself in the form of a Flood.

Literary and dramatic works are full of antagonists who, as they often said about Lady Macbeth, “steal the show.” Moby Dick. Mr. Hyde. Iago. Hannibal Lecter, Darth Vader, shark in Jaws — evil, evil, evil. (Fun fact: Iago has more lines in Othello than the main character. Watching Iago in action, it’s hard not to think about Frank Underwood played by Kevin Spacey from the American version of “House of Cards”.) One of our catchphrases, which we have been repeating to each other for many years, says: “A story is only as good as its villain is good.” If you want to create a good villain, you need to keep in mind that he considers himself the star of the show or the hero of the game. In a successful story, there should be an excellent antagonist, but remember that the antagonist does not necessarily have to be the embodiment of absolute evil (for example, a maniac tying his victims to the rails, although this option is also not bad). The only requirement for him is that his desires and the desires of our hero contradict each other. They are in conflict with each other. As they say: “There must be only one left!” One of the most memorable “kindly” antagonists in the movie is US Marshal Samuel Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones) in the movie “The Fugitive”. The film is based on his pursuit of a wrongly convicted fugitive, Dr. Richard Kimble (Harrison Ford).

The real villain, the so-called “One-Armed”, who actually killed Kimble’s wife, pales in comparison to Samuel Gerard.

When creating a villain, you should use the same principles that we discussed above when creating a hero. What does he want? What does he need? How do these goals contradict each other?

Yes, the book is called “Kill the Dragon”. And yes, the villain can really be a dragon. But this dragon does not know that he is a villain. If the plot of your game tells about a knight on a white horse who must rescue a princess from the dragon’s lair, then the dragon thinks that the game is based on a story about a man who invaded his house: about a man who destroys his habitat, builds ridiculous castles on cleared forest lands that once served as a place hunting deer, wild boar and bears. For a dragon, a knight on a white horse is the villain! You should be able to look at the game through the lens of the villain’s story. (If you haven’t seen the cartoon “Ralph” yet, put the book down, find it and watch it. This is an excellent example of a story told from the point of view of a “villain”. And he was a huge success!)

The Portal game has GLaDOS, an artificial intelligence with the habits of a sociopathic manipulator, whose task is to test the experimental Chell. Vario — Mario’s sworn enemy — turned out to be so popular that two separate games, Wario Land and WarioWare, were dedicated to him. The hero of the game Darksiders II is Death (yes, the same Death). The game BioShock depicts business magnate Andrew Ryan, leading a horde of mutants and defending his fallen and abused Utopia. The image of this iconic character was based on such figures as Howard Hughes, Ayn Rand and Walt Disney.

Do all games have villains? In one form or another, yes. A game without obstacles is not a game; these obstacles are personified by villains. They can be impersonal, as in the game Limbo, where the antagonist is the environment, or personified, like Bowser, who appeared in Super Mario Bros. like a villain who tried to steal Princess Peach. Do not forget about the smug, cheeky green pigs from Angry Birds. From space zombies in Dead Space to ground zombies in … almost any game of the genre “survival horror”, because someone has to try to prevent the game character from killing the dragon.

AND THE DRAGON GOES TO… THE BEST NPC SUPPORT

As the game character (PC) wanders through the game — either completing the main quest or exploring the open world of the sandbox — he meets non-player characters (Non-Player Characters, they are also NPCs). These characters appear in the game to give hints and hints, tell a backstory, indicate a direction, serve as companions or just for the sake of a comic moment. NPCs help bring the game world to life.

Among game developers, especially those created on the basis of other works of fiction, there is a noticeable tendency to turn the most powerful characters of the game into NPCs, in whose shadow (or on whose behalf) the main character acts.

In the Portal game, the NPC-sociopath GLaDOS is much more vividly remembered, and not the wordless Chell. The Godfather: The Game begins as a very minor member of the Corleone organization, and not as Vito or Michael Corleone, although later the player meets Vito and carries out his orders. In Star Wars: The Force Unleashed we play for Starkiller, nicknamed “Darth Vader’s secret disciple”, but not for Darth Vader himself (except for the training level). Good characters disappoint and surprise us. It has always been so (Hamlet), it will continue to be so (Walter White, Don Draper). The protagonists of video games follow them closely. For a long time, the most interesting characters on the screen could be NPCs. The recently released Assassin’s Creed: Unity game boasts ten thousand individual NPCs. Ellie in the game The Last of Us for the most part also plays the role of an NPC, but becomes the main character when Joel is wounded. An NPC is a “supporting cast.” They complement the image of the main character. They challenge the hero on his path of action.