chaosmonger's Nicola Piovesan on old school sci-fi, avoiding moon logic puzzles, and breaking the fourth wall

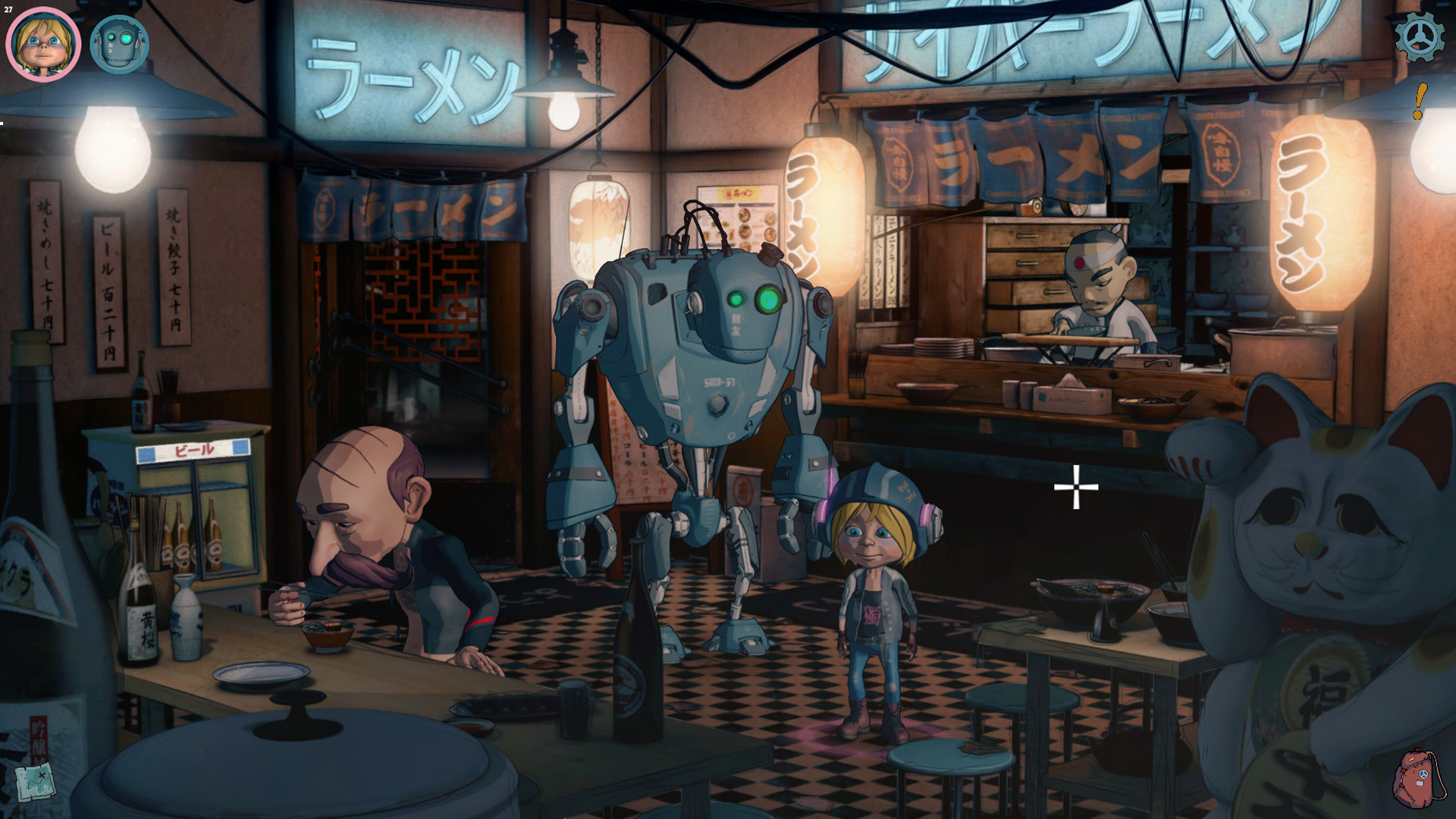

ENCODYA is a cyberpunk point-and-click adventure game that came out on PC on Jauary 26. We caught up with ENCODYA’s developer Nicola Piovesan to discuss the game and the team behind it at chaosmonger studio.

Nicola Piovesan

film producer and director, game designer,

head of chaosmonger studio

About Nicola and chaosmonger studio

Oleg Nesterenko, managing editor at GWO: Niсola, you started as a filmmaker. What made you want to explore the medium of the video game?

I always crave to learn something new and I like to challenge myself all the time, to explore new languages. Even in the film industry, I was always doing different things (from documentaries to animation, from music videos to the 80s aesthetic science fiction). When I was running my Kickstarter for the Robot Will Protect You short film, I noticed lot of attention from the gaming community, so I thought: why not, let’s make a game with the same characters and setting! That’s how ENCODYA was born.

Robot Will Protect You (2018) – Trailer

Several words about the studio please?

I founded chaosmonger studio back in the early 2000s in Bologna, Italy, and now it’s based in Estonia. It has always been just me, plus a series of freelancers collaborating on a project-by-project basis. When we shoot movies, then we gather all together (be that in Italy, Estonia, Sweden or anywhere else), when it’s animation or game development, then we all work remotely. We did even before the covid pandemic. So basically chaosmonger studio is me and a bunch of people scattered all around the world who change often depending on the project (there are a few persons, though, that I collaborate with almost every time). I dream of having a big studio with 15-20 people working there full-ime, but for now we are truly small and indie.

Studios that rely on revenue streams from non-gaming projects often choose to self-publish. Have you considered it?

Since we are rather small, we don’t have the resources to fund a game on our own, nor to distribute it. That’s why our latest projects were funded through Kickstarter and that’s why I now have Assemble Entertainment publishing ENCODYA. Thanks to them, I saved lot of energy and headaches, since they handled tons of aspects I had no idea about, especially considering that this is my first game. I’ve considered publishing on my own and I will consider it also for the future, but our studio needs to grow, as does our reputation. And I hope ENCODYA will help in that sense.

ENCODYA features fantastic voice acting and music. Did you have it all recorded before the pandemic?

We also did it remotely! Basically we didn’t have a single dubbing studio, but various independent voice actors – again from all around the world – that recorded the lines of dialogue in their own homestudios during the pandemic and sent us the files. Of course I’ve tried my best to coordinate their performances remotely, but it wasn’t an easy task. Overall, I think the result is very good considering the conditions. Same happened with the music and the sound design: sharing ideas remotely and sending files back and forth until we had a great result. This whole process took months and was handled mostly during the pandemic. Fun fact: I never met in real life the music composer of ENCODYA, nor the majority of the cast and crew!

ENCODYA gameplay trailer

About ENCODYA

So there’s a game called ENCODYA and your earlier film called The Robot Will Protect You. Both are set in the same universe. What exactly is the relationship between the two?

I initially completed an 11 minute film, Robot Will Protect You, in December 2018. As I said earlier, only later did I decide to make a game with the same characters and setting, but a brand new story. So, in a way, the short film is some sort of prologue and introduction to the characters and settings of ENCODYA. While I was developing the game, the short film started travelling film festivals around the world, including some Oscar qualifying ones, winning about 20 awards. So I wish it could also become a feature animated film, but it’s too early to say.

How does your experience as a filmmaker inform your approach to game design?

Coming from a filmmaking background, which also included animation, surely helped me put together all the assets (characters, backgrounds, music, sfx, voice actors, etc.) and the right people to handle them. And also in the narrative and writing, ENCODYA follows somehow the classic three-act Hollywood scheme for scriptwriting. The hardest part, coming from film industry, was learning how to code a game and to think about the story in a non-linear way. But thanks to lots of online tools and communities, I managed to program ENCODYA almost entirely on my own.

I guess the game feels rather old school. Were you a fan of the point-and-click adventure games of the Amiga days?

Definitely. I walked my first steps with Commodore computers, I started with a C16 back in the late 80s, then moved to a C64, an Amiga 600 and finally an Amiga 1200, that had been my computer for a long time (I moved to a Windows PC only in 2001!). So yeah, when I was a teenager I played tons of adventure games (mostly LucasArts ones) and for me it was somehow “safer” to enter the world of game development with a genre I was confident with. Not to mention that adventure games are rather “cinematic.” In a way, they are some sort of interactive movies. So it was the most logical genre to start with. That said, last year I also started developing a game that is totally different – a platformer metroidvania with tons of humor – called Clunky Hero, and I have a couple of new ideas for different games that aren’t p’n’c.

Given the cyberpunk genre, you could’ve totally gone for a bunch of mechanical puzzles like in Machinarium, for example, which are somewhat detached from the narrative. All your puzzles, however, are very grounded in the story. So, which came first? The puzzles or the plot?

The puzzles came very late. I first had characters and settings from the short film, then I wrote a brand new story, in the shape of a short synopsis, which I then made into a treatment and later into the 5 parts of the game. So all the characters and narrative elements were already there, and I created the puzzles to fit the story and characters, not viceversa. I guess that coming from the film industry, it was easier that way.

Many players, me included, felt that some solutions were far from obvious. Not that they should be easy, of course… When devising a puzzle, how do you make sure it does stretch the imagination without becoming too extravagant?

This is one of the hardest parts to design for a point-and-click game. I’ve read many reviews of other games out there before designing the puzzles of ENCODYA. Lots of players were disappointed when a puzzle was relying on what is called “moon logic” (when it doesn’t make any sense, like using a monkey as a wrench). But they were also disappointed when something was too obvious and logical, therefore easy. So I’ve tried to find a good balance, also in the hope that ENCODYA could reach the widest audience possible: skilled p’n’c adventurer might find it a bit easy (and I’ve got some feedback in that sense), while casual gamers might find it rather complicated, but overall the logic of the puzzles should be clear enough for the majority of players. My secret word in the process was “plausible,” meaning something that is not so obvious, and yet not too absurd, something that “it could be”: like throwing a sticky substance to a robot to clog its mechanism, or sharpening a flat stone with a hydraulic press to cut a vine.

In the story, there are mentions of the Russian-Chinese Army or the alliance between Germany and Japan. Then there’s environmental storytelling. How extensive is the lore that you had to create for the game?

I’ve been creating the world of Neo Berlin for a few years already. It all started with a short film called Attack of the Cyber Octopuses, a 20 minute live action tribute to the 80s sci-fi, entirely made with practical effects and miniatures. It’s set in 2079, 17 years after ENCODYA, and one of the characters is called Tina… (!) That said, I’ve been writing pages about that world and there are many hints about it around ENCODYA, especially when talking with old people (like the Fatemancer at Bright Alley or Frank at the Black Market), as well as reading the various files that you can find in the terminals around the city. So, the “world building” process is something I truly took care of and I intend to expand that universe also in other future projects, be it animation feature films, live action shorts or video games!

Attack of the Cyber Octopuses (2017) trailer

The world of Neo Berlin feels very alive due to the sheer amount of detail and dialogue. Then you even managed to make the hint mechanic part of the in-game reality, rather than a UI feature. But the characters themselves keep breaking the fourth wall. Did you just do it for fun? Or is it part of the story’s main message regarding real life and virtual spaces?

It’s both! Well, first of all, it’s true the characters break the fourth wall, but it doesn’t happen that often, so I hope this doesn’t ruin player immersion. However, they are there for two reasons: 1) I truly love them, and they make me laugh. Monkey Island also often broke the fourth wall, and for me this kind of jokes has always been very funny. 2) It’s to remind the player it’s all a simulation in some sort of “matrioska” doll of realities.

Let me explain the second point: in the demo there was even a dialogue between Tina and Sam when Tina asked if they were just characters of an adventure game. This was maybe too much, but at the same time there are theories suggesting that we (me and you in the real world) could be as well just part of some super-advanced simulation (I guess also Elon Musk mentioned it). So in ENCODYA, there are also realities within realities.

SPOILER ALERT. At the end, we are inside the mayor’s “limbo,” which is a virtual world built inside the forest of ENCODYA, which is itself a virtual space built inside the ordinary cyberspace, the internet of Neo Berlin, the “real world” of Tina and Sam, which is not real because we as players are controlling them… And maybe someone is controlling us right now, who knows? So, in a way, the characters of ENCODYA know they are just “replicants,” like in Blade Runner.

The game is surprisingly political. Some mature themes are hinted at. There’s alcoholism. There’s defacing political posters. There’s contractual slavery. Why did you go with a child protagonist for a story like this?

I’m not sure it’s so political or that the subjects you mentioned are “dominant” in the game. As stated in the disclaimer at the beginning of ENCODYA, we are not taking any side. This is super important for me. The only thing we are against (and it’s also mentioned in the disclaimer) is when politicians and big corporations try to control our lives through media. They can be from left, right, center, it doesn’t matter. When it happens, I feel our freedom is in danger. A concept well explained in docudrama The Social Dilemma (2020), for instance. It’s a difficult topic of course, but I didn’t want it to be too heavy or too dominant in my game. I still think ENCODYA can be played by 10 year old kids, without feeling any political or other heavy themes at all. But what I wanted was to create different “layers”: a kid might enjoy just the charming story of friendship between Tina and Sam, an adult might see the other topics as well. Also, Tina doesn’t have a political view. She is simply an orphan, who lives breaking the law and therefore she hates authority, because police is always chasing her and because cyberspace killed her mother. That’s why she is against the mayor or the corporations. It has nothing to do with supporting a political part. Furthermore, as Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki have demonstrated with their movies, when you see hard topics through the eyes of a kid, you can get them straight to your heart.

There are “red herrings” in the game. Objects that you never use. Likewise, there are some storylines that do not necessarily lead anywhere. Like the redheaded twins never make Tina meet her part of the deal they made. What is it? A bug or a feature?

If we were ending each storyline we opened, we could have made an RPG with 30 hours of gameplay! But with our resources and considering the genre and the main narrative of ENCODYA, I think it’s totally fine to not close some of the possible storylines. Both because the player can imagine somehow on their own how that narrative could end, and also because it leaves many options open for a possible second chapter. Maybe there’ll be an ENCODYA 2, where you see Tina doing a favor for the twins!

ENCODYA was your first game. What did it teach you that you will be using or avoiding in your future projects?

Of course I made lot of mistakes while deloping the game, things I could have approached differently, especially on the pipeline of some tasks. But well, it was all experience and surely I’ll manage things differently for the next project. Hard to tell something specific, it’s more about the workflow in general.

Overall, it taught me that game development can be very stressful but also super rewarding: there are thousands of people playing ENCODYA, and I receive many messages from people I don’t know telling me about the emotions they felt playing my game. This is the best reward ever and makes me forget of all troubles I had to overcome to create this game with a super low budget.

Thank you!