AppMagic breaks down key trends in Merge games to see whether devs should jump into this genre in 2022

Merge has been one of the ever-evolving genres on mobile for a while. AppMagic has interviewed several games industry experts to put the entire category under the microscope. This article highlights the key trends while trying to answer the question of whether the Merge genre is worth trying now.

Olga Sobolevskaya, Max Samorukov

Since the release of Merge Dragons!, and as more hit titles of the same genre kept coming along, the gamedev industry has been buzzing with excitement over Merge games: a truly spectacular trend that is definitely worth a keen look. What’s up with this enthusiasm, anyway? Maybe, many developers are constantly on the lookout for the next big thing, hoping to be among the first to jump on board and secure a tasty slice of the market. Or maybe, games of this genre are simply deemed relatively inexpensive to produce and hence appeal to a wide range of game developers.

So then: has the Merge genre lived up to the industry’s expectations? And does it still seem to have the same potential as it did 3 to 5 years ago?

To get a truly good look at the genre in question, we interviewed a few industry experts from 5 different companies, including:

- Egor Pavlyuk and Alina Zlotnik: lead business development manager and producer respectively at AppQuantum, a publishing company;

- Sergei Belikov: former senior game designer of EverMerge, one of the most successful Merge games;

- Maxim Babichev: CBDO at Green Grey, an international interactive entertainment company;

- Rustam Batyrkhanov: CEO at Happy Games Studio;

- Andrii Chaika: Co-Founder at 4Enjoy studio.

We tried to match our experts’ comments with available market data to build the most objective and consistent case possible. And here we go!

What Is A Merge Game? (And mind the hybrids)

First of all, let’s define what we refer to as “Merge games”. Now, there shouldn’t be any ambiguity regarding titles with classical Merge mechanics for their core gameplay. However, there is certain room for interpretation when it comes to offerings with Merge elements embedded in their core gameplay that are, nevertheless, a different genre in essence. Just think Top War, Gold & Goblins, or Rush Royale.

For example, in Top War, the Merge mechanics carry an engagement function above all, since their purpose is to increase retention. However, by midgame, the user finds themselves playing a clear 4X Strategy.

As for Rush Royale, this game is much closer to Clash Royale or the Tower Defense genre than to Merge games. It’s built around real-time multi-unit battles with a lot of direct control and a strong strategic component; in mobile gaming, titles of this kind are often referred to as RTS (real-time strategy).

Games like these, “infused” with a Merge component, are definitely curious and worth a study; many of our interviewees admit that this line of game design presents genuine commercial interest. However, since these games should ideally be classified as genres other than Merge, they are somewhat outside our scope this time.

Let’s just point out that one of the key qualities of merging as a core mechanic is its great addictiveness. Thus, combining elements of Merge mechanics along with strong retention and monetization solutions from other genres sounds like a noteworthy idea with a broad spectrum of applicable cases.

Merge Games: Simple Vs. Complex

When analyzing various market indicators for the genre, we note down parameters such as size, size dynamics, degree of market monopolization, diversity, and presence of successful new titles. For this analysis to be relevant, we must make sure that the studied games of the genre are appropriately homogeneous across their main key characteristics: core gameplay, metagame, target audience, etc. Simply speaking, we must ensure that we are not just chasing after some means and averages for the sake of it, all the while comparing apples to oranges—but are actually identifying statistics that make sense for further application.

For starters, we broke down Merge games into two broad categories: with and without the metagame. These two are drastically different from one another in nearly every aspect: costs and the difficulty of development; user acquisition strategy; lifetime in general and LTV in particular; mechanics and their combinations; end goals; and last but not least, the feel and vibe.

Merge titles without the metagame are generally basic puzzles with no proper end goals, no narrative and limited progress options. Games with a meta, in turn, are serious products that are hard to put together and carry entirely different commercial expectations.

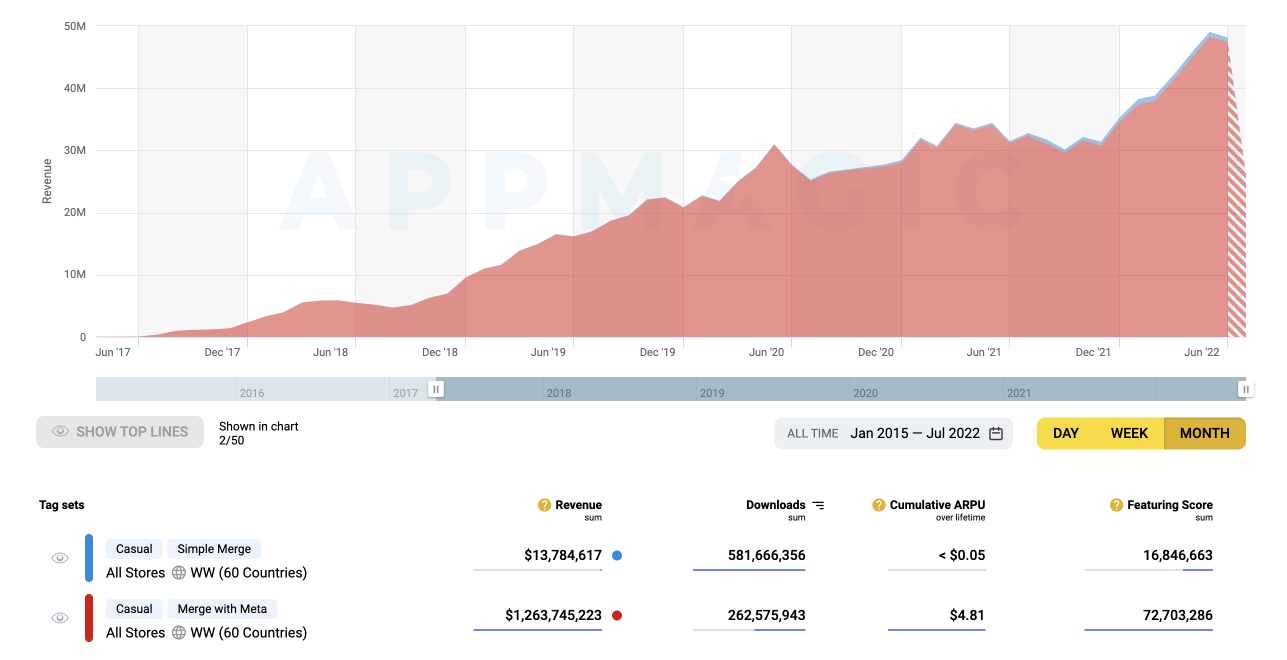

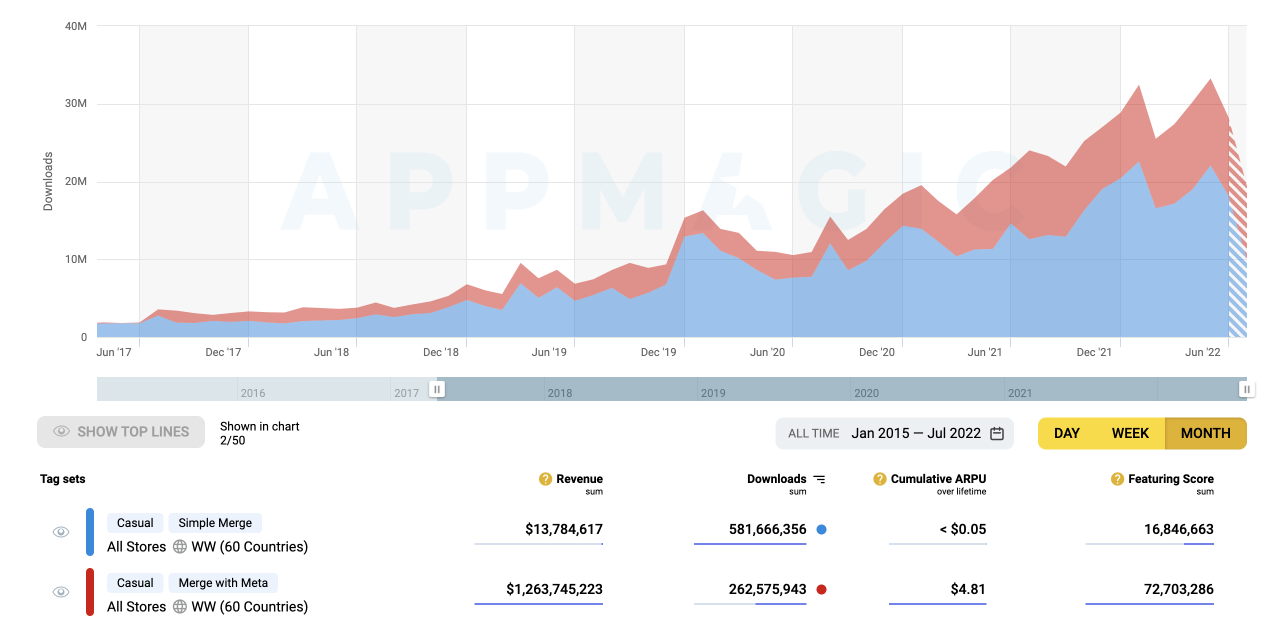

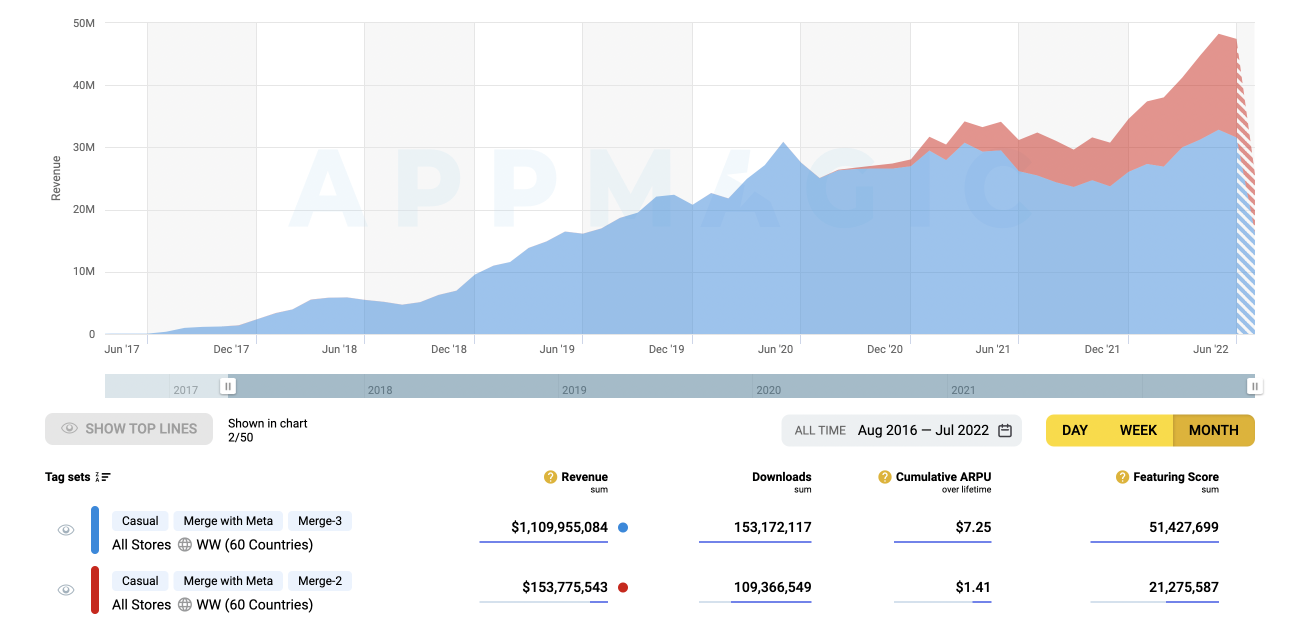

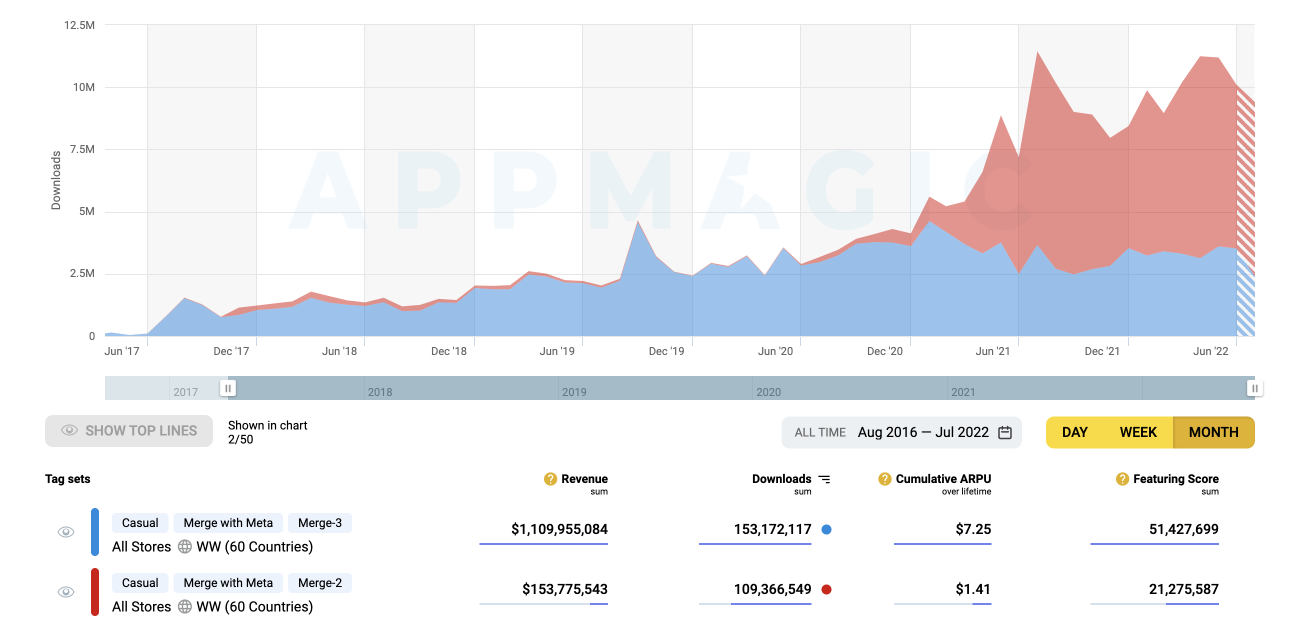

Click on the images to check the source data

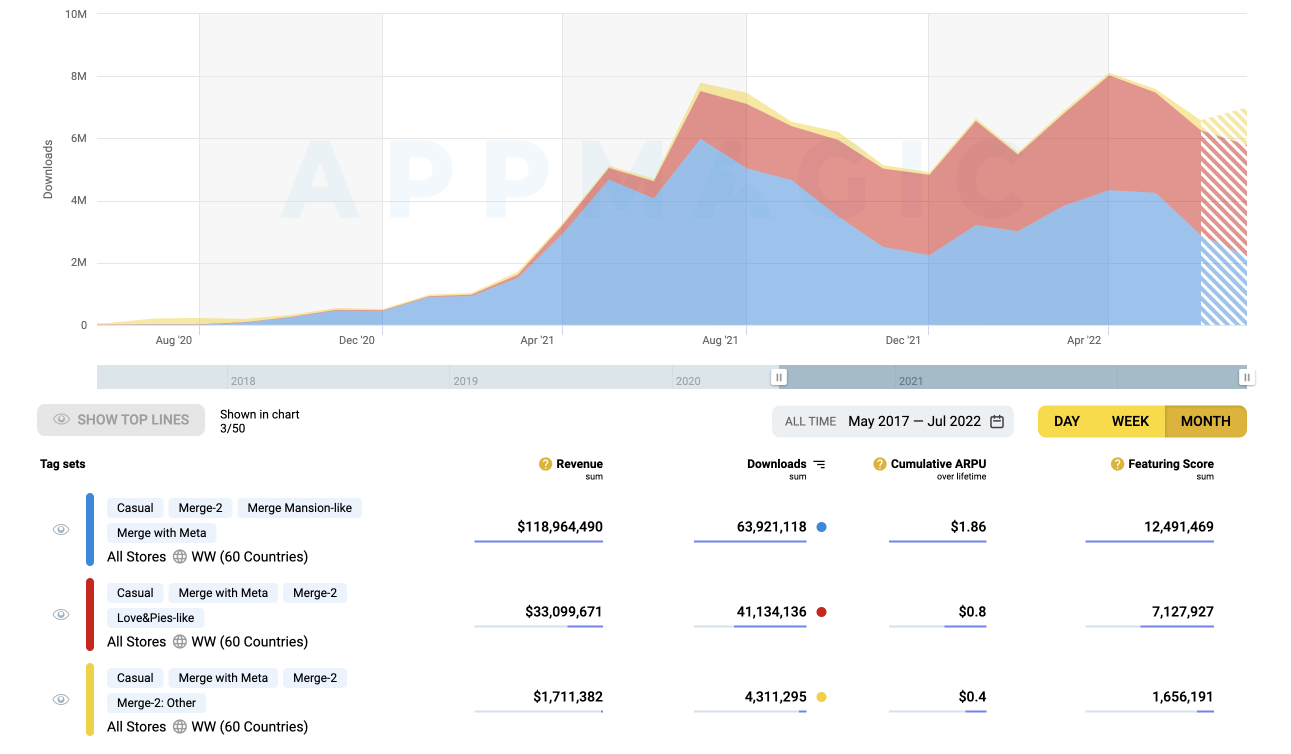

The graphs make it clear that simple Merge games generate next to zero iAP (in-app purchase-based) revenue; meanwhile, their downloads are twice as high as for titles with a metagame. Question is, then, what’s the story with their iAA (in-app ad-based) earnings? Can a game of this kind generate serious revenue with ads?

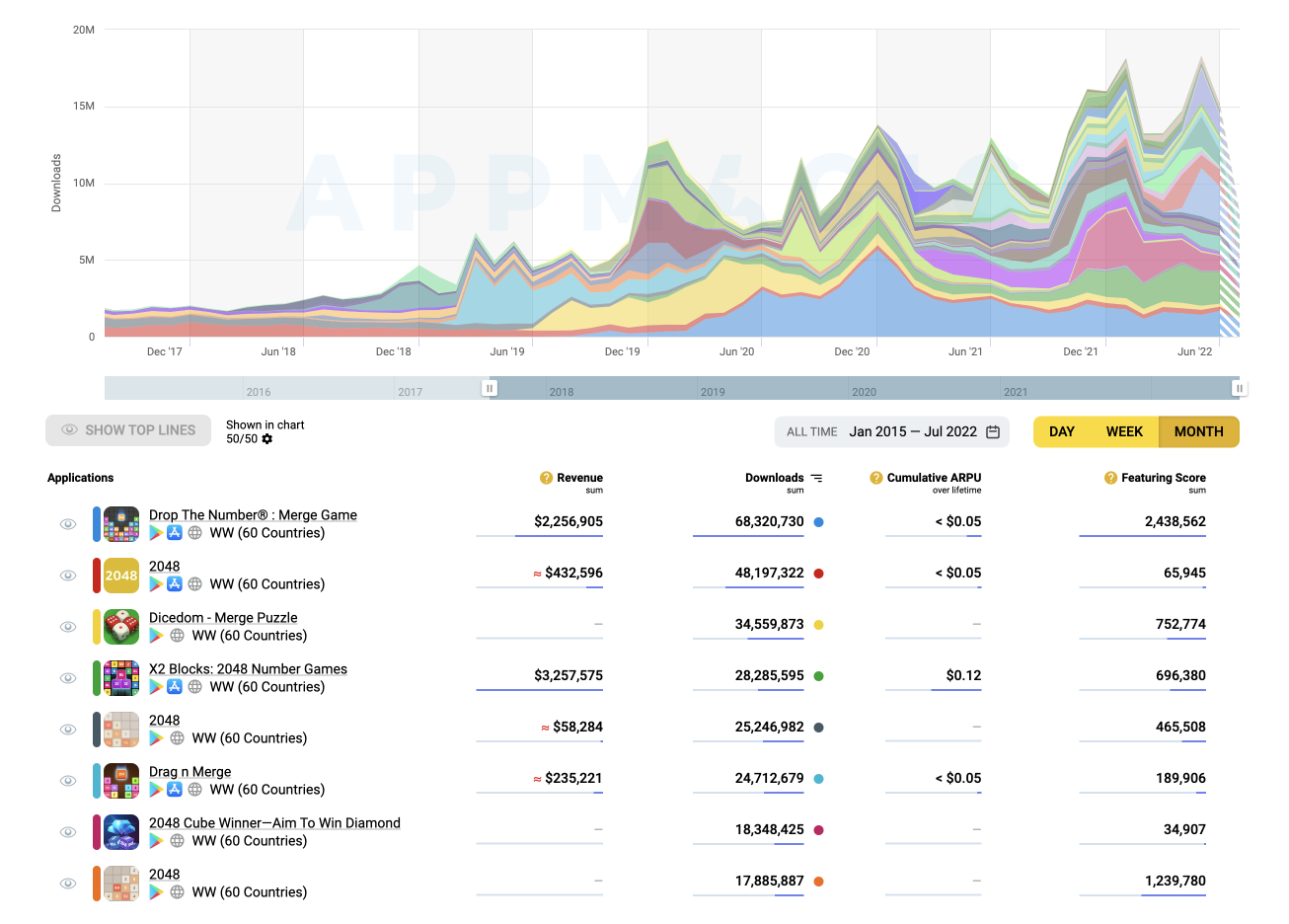

If we take a closer look at titles with basic merge mechanics that deliver the largest number of downloads, we will see that most of them resemble Hypercasual games design-wise: high-frequency interstitial ads, very basic gameplay and no metagame. Now, looking at market fluctuations in this segment, we will also see that it is highly dynamic, with games coming and going all the time and only a handful sticking around for long. This, too, is typical for Hypercasuals:

Click on the image to check the source data

Here, one graph visualizing the downloads is enough, since the segment’s iAP revenue is negligible, just like with Hypercasual games.

The conjecture is that, in essence, simple Merge games with no meta resemble the Hypercasual segment a lot: their game design and feel; monetization and comparatively simple production; typical product lifecycle, the user’s lifetime and LTV — all Hypercasual. Therefore, this game category has little to no impact on this article’s case.

Now, Merge games with a metagame are a whole other business.

Complex Merge Games: Merge-2 vs Merge-3

Further dividing games into Merge-2s and Merge-3s is common practice. And while this approach is reasonable, that’s not because it makes such a big difference whether we are merging two or three elements during play. The reason is more about the key (and very different) product concepts that have been historically established for games of this kind.

A Мerge-2 and a Мerge-3/5 with a meta differ drastically. See for yourself:

- Merge-2 games separate core gameplay and the metagame: you’ll find the core mechanics on the grid, while meta happens on a different playfield altogether. One of this solution’s immediate implications is that the Merge-2s’ metagame is easily adjusted or even replaced. With Merge-3s, on the other hand, meta is “fused” into core gameplay, which strongly affects the feel of the game;

- As a result of this “infusion”, Merge-3s’ core gameplay has changed a lot. Moreover, most of the Merge-3 games are actually Merge-5s: merging 3 items gets you 1 next-level item; but merging 5 awards you 2 next-level items, so users are strongly incentivized to try and merge 5 whenever they can. As a result, core gameplay in Merge-3/5 games is leaning less towards merging as such and more towards item arrangement and space optimization. All this makes general gameplay feel very different from Merge-2 games;

- A Merge-2 grid is usually a limited size, matching the screen. With Merge-3 games, the playfield normally goes beyond the screen, and you need to “explore” to gradually unlock it;

- A Merge-3 playfield features characters. The mechanics of interaction with them may vary, but the core function is similar: you need these characters to unlock new territories on the playfield;

- A typical game session is longer for Merge-3 games, and it is structured differently. The player can prolong their game session by optimizing items on the field; and the game will be wired to encourage longer sessions, which works in favor of long-term retention, too. As a result, Merge-3 games deliver a more versatile and complex core gameplay with lower early and higher long-term retention than Merge-2 games do.

Click on the images to check the source data

If we look at these two groups’ aggregate performance, we’ll see immediately that Merge-3 games’ iAP revenue is expressly higher than for Merge-2s, while Merge-3 games demonstrate lower total downloads. Overall, this translates into a massive difference in the iAP LTVs between Merge-3 and Merge-2 games: $7.4 vs $1.4 (worldwide) and $17.0 vs $4.2 (USA) respectively.

So we’re all good, right? We’ve got our homogeneous sub-genres all figured out and ready for research. Or…?

Merge-3/5

Мerge-3 games comprise two groups of games that are very similar to one another within each group.

The first one includes the descendants of Merge Dragons! — the first mega successful game in the Merge genre: it is widely regarded as the title that fueled the game developers’ mass interest in the genre. All these games (let’s call them MDLs for Merge Dragons!-likes) resemble one another closely, sometimes almost twin-like—that is, regarding their game design solutions, feel and even the minor details.

The second group can be similarly defined as the EverMerge-inspired titles (EMLs further down for EverMerge-likes), and they are also very much alike to one another.

These two groups sport a few expressed differences:

- MDLs offer levels on top of the main location, and introducing limitations on completing them (say, time constraints or limited moves) puts monetizing pressure on the user, forcing them to acquire boosters or additional attempts to complete the level. There is nothing of the sort in any other Merge games;

- MDLs feature a signature mechanic of “reviving the dead land” with the help of special creatures (like dragons). You unlock new territories as you accumulate and merge these creatures. In EMLs, there is nothing of the sort, but instead new territories are unlocked with the use of special rare elements: they are generated by means of a rather complex mechanic that is essentially a mix of merging and farming (with characters, crops and crafts);

- It should also be noted that both MDLs and EMLs have their own distinct extensive sets of minor mechanics that clearly separate the two groups of each other, all the while making games inside each group very similar.

Actually, there is a third group of Merge-3/5 games: all the titles that do not classify as the first or the second one. This subset isn’t actually small, but its aggregate performance is pretty poor, i.e. this segment offers no successful game concepts that present good alternatives to either Merge Dragons! or EverMerge.

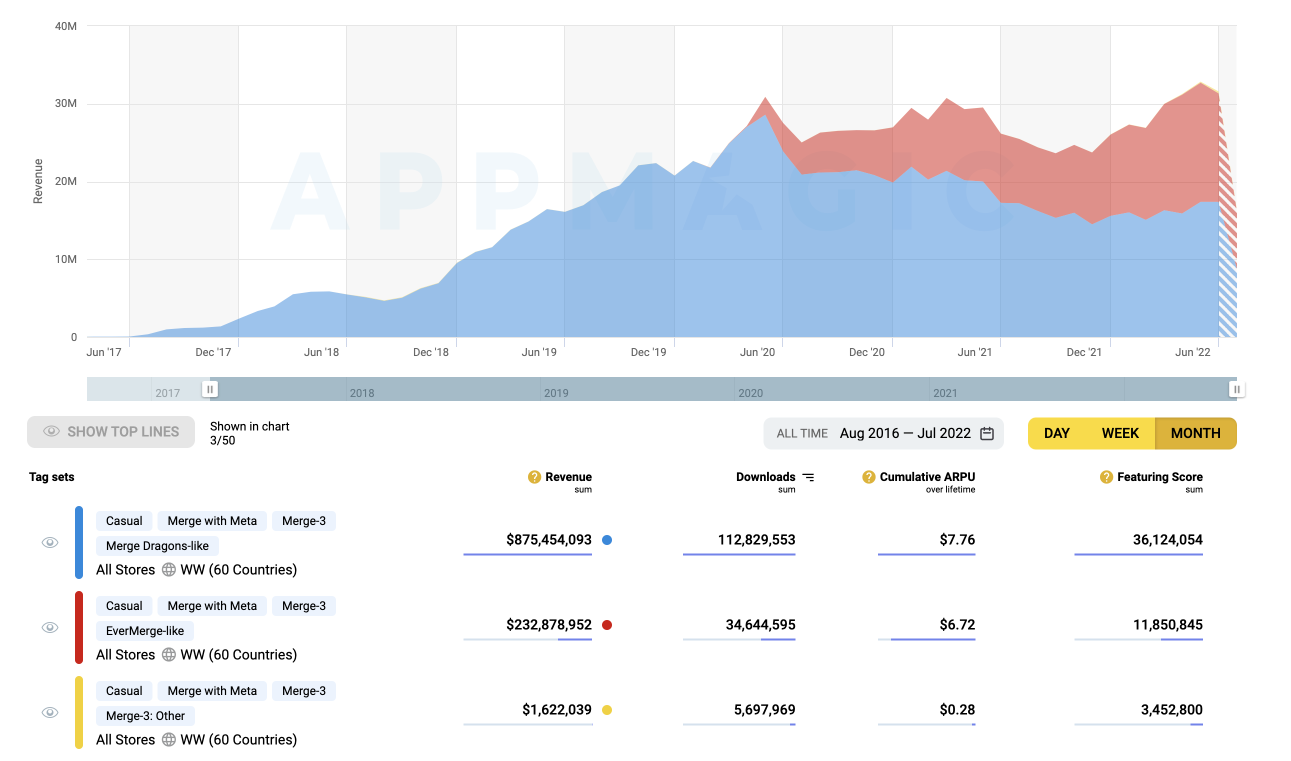

Click on the images to check the source data

Merge-3/5: Merge Dragons!-like

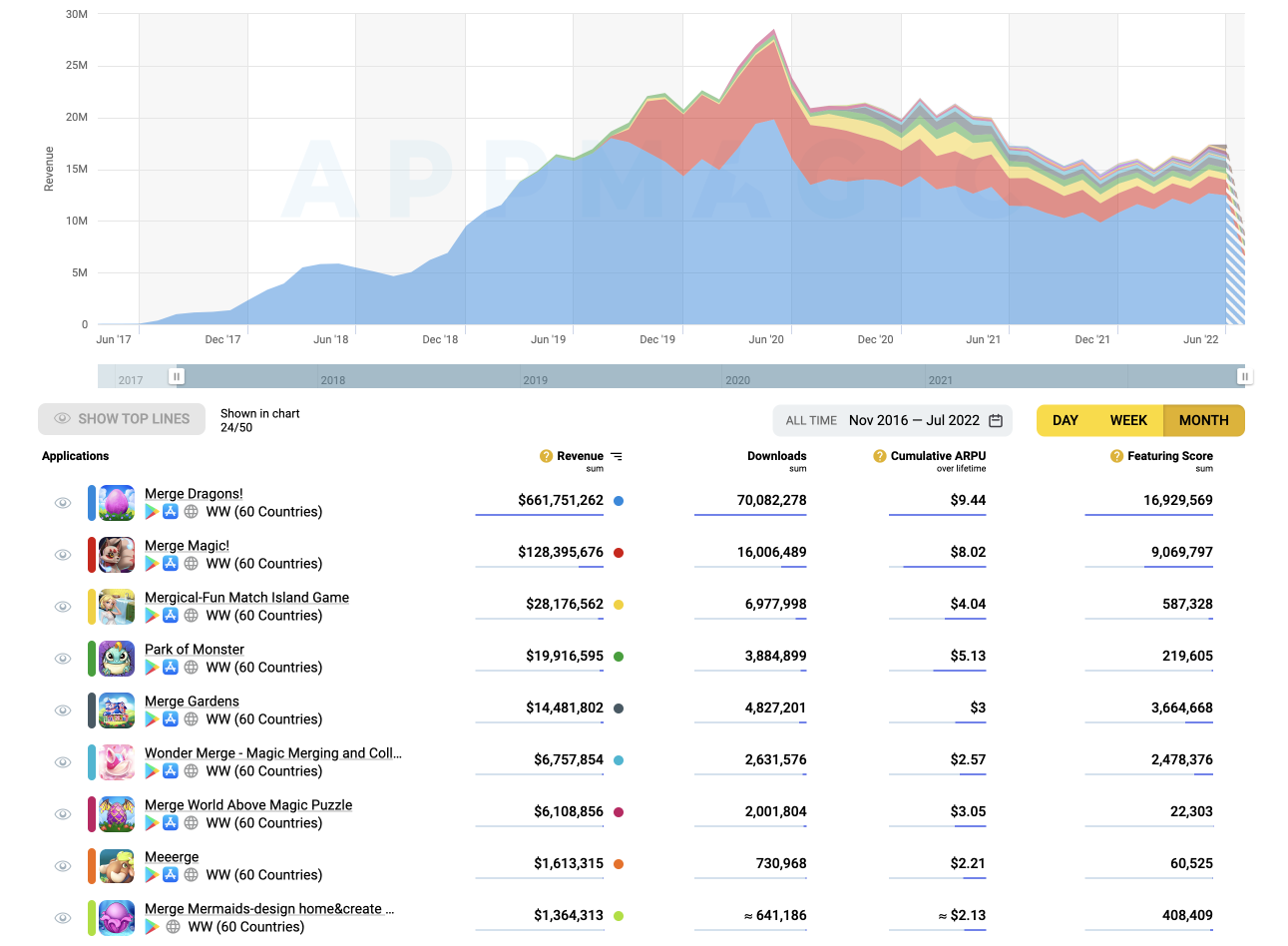

Here’s a closer look at the first group of the Merge-3/5 games:

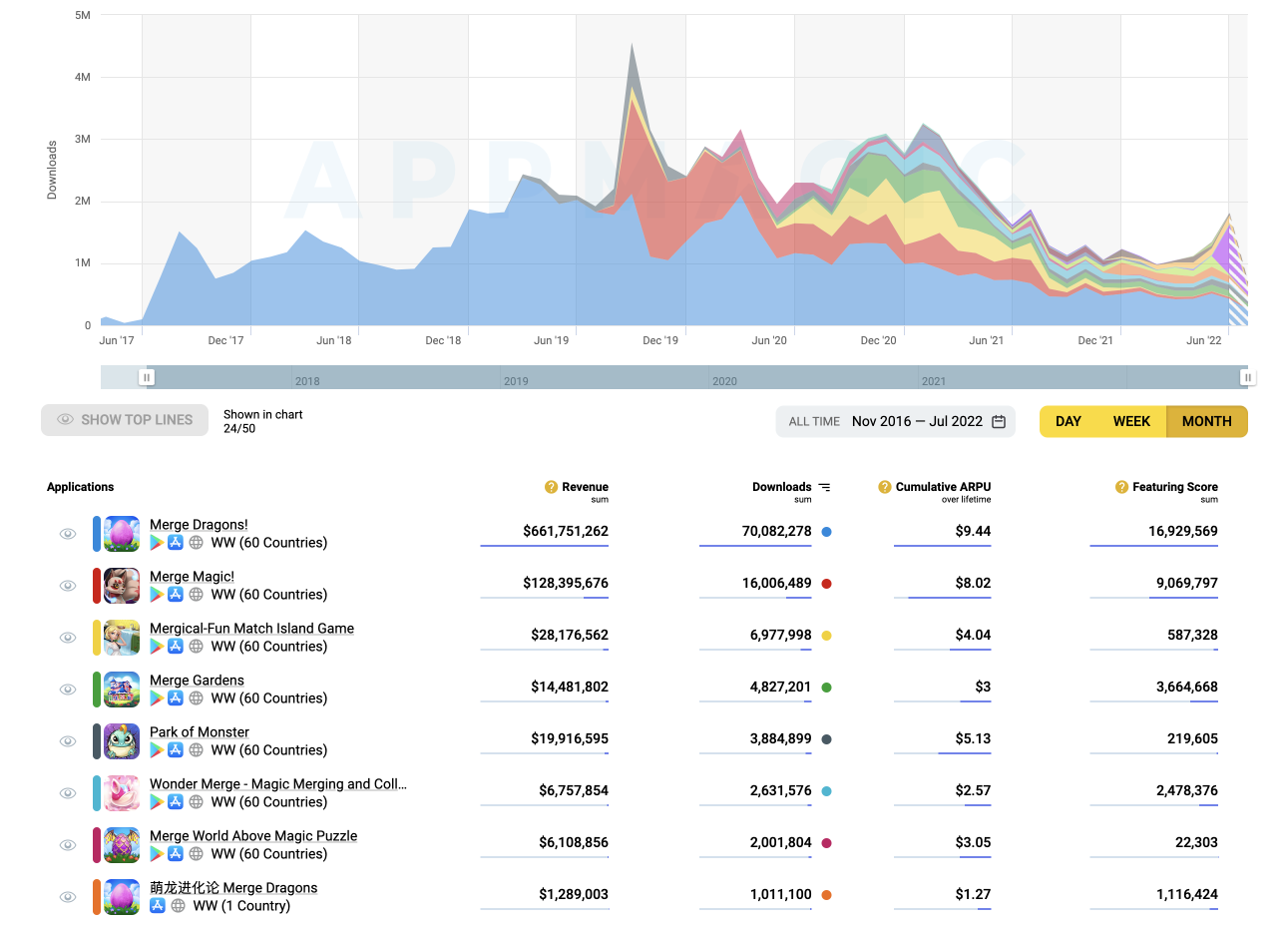

Click on the images to check the source data

What does the market data tell us then? To begin with, it’s clear right away that this is a high LTV genre, so we should be looking at the Revenue first.

Two of the largest titles of this sub-genre — Merge Dragons! and Merge Magic! — were both developed by Gram Games, and they both came out ages ago; there have been no newcomers too striking since then, even though there have been quite a few of those who tried. In fact, even the more recent Merge-3 games by Gram Games themselves didn’t show any notable performance. Moreover, aggregate downloads of all the games of this kind have been falling over the past few years, which indicates that this sub-genre cannot compete too well over user traffic at this stage of its evolution.

In defense of all those other titles, some of them earn pretty good money: out of the games released in the past couple of years, there are a few that make a decent $200-600К per month. However, they don’t seem to be growing and appear to be struggling with scaling user acquisition.

After all, the absolute revenue figures of these games are not exactly what you’d call the holy grail for most gamedev companies. Developing a quality game of the Merge Dragons! type is not exactly cheap as chips, so you’d want a decent reward for your efforts when you’re done. Our interviewees estimate that it should take about a year of work by a team of 15 to 20 people to produce one, and that’s ignoring any team scaling when it comes to post-launch live-ops and marketing.

Therefore, it will probably not be a long shot stating that this Merge-3 market sub-genre at its current step of evolution is approaching its dead-end. We haven’t seen new ideas that lead new titles to success for many years now; we haven’t seen successful new titles employing traditional ideas either; market leaders have been the same for years. All these markers suggest that the genre is a real trap for newcomers: they sink before you even learn about them.

All our interviewees, too, weren’t particularly enthusiastic about this sub-genre.

Merge-3/5: EverMerge-like

Moving on to the second group of Merge-3/5 games: the titles that fall into this category are all very much alike one another and must have certainly been inspired by EverMerge.

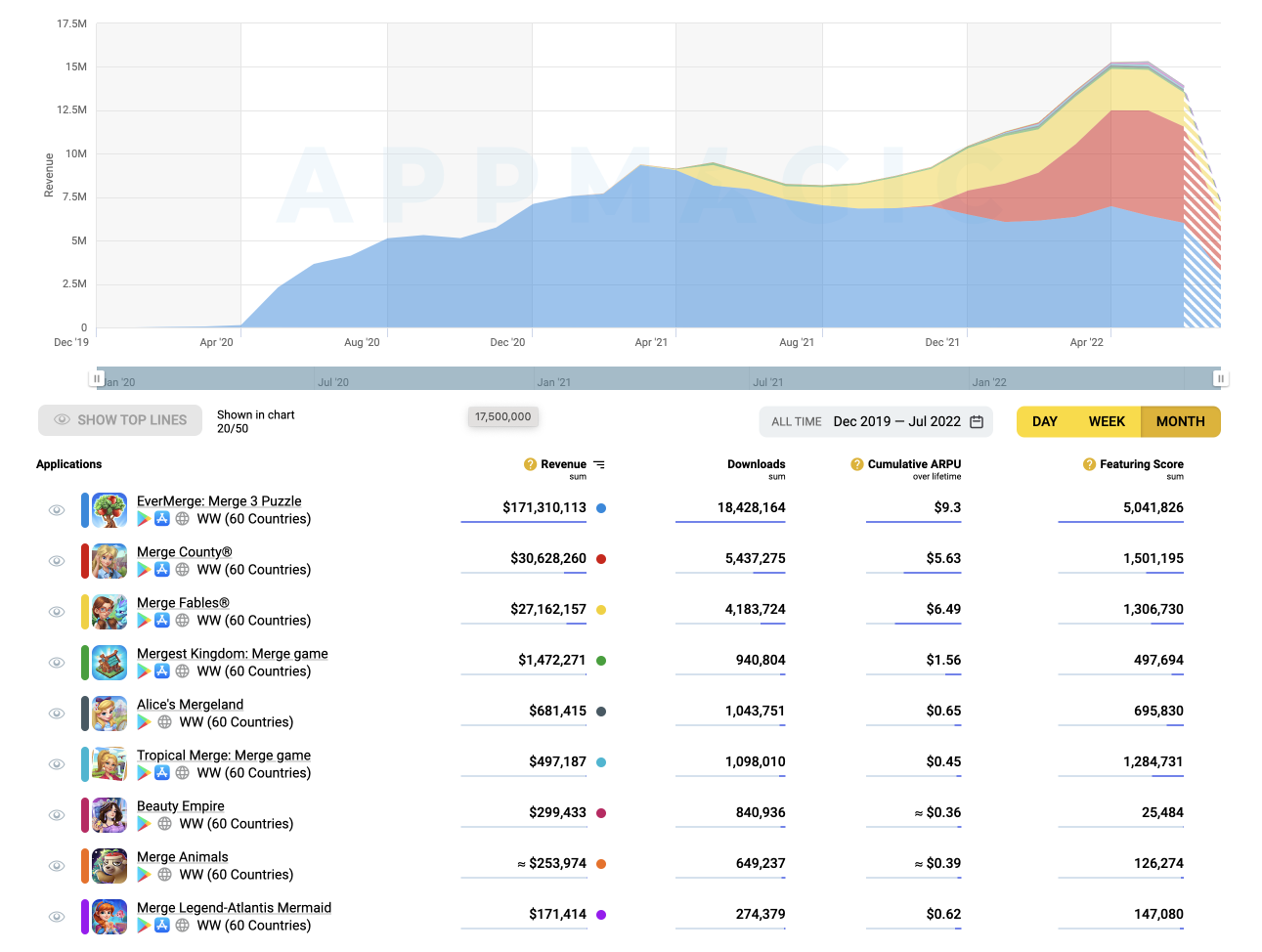

Click on the images to check the source data

Successful games of this genre, same as MDLs, typically demonstrate high LTV, so we should focus on the left-hand-side graph. It tells us right away that three games account for 99% of revenue while all other titles earn just about nothing.

Maybe it’s just that the sub-genre is pretty young and doesn’t feature too many games yet, right? Nope: there are plenty of quality releases but very few successful ones.

Nevertheless, the emergence of two new highly successful EverMerge followers over the past 18 months indicates that there is still room in the market to squeeze in new players.

And what about the evolution of the sub-genre? Well, there are a few points to note here.

Probably the most explicit observation is that Merge County, the youngest of the three current market leaders (and arguably the one with the greatest potential), has traded the genre’s traditional Fantasy setting for Real Life. The latter is deemed a good solution for those who seek to expand their target audience. Yet still, if you have an outstandingly successful and well-established reference setting for a genre, the decision to go for a different one is considered rather risky. Well, in the case of Merge County, it appears to have paid off.

Is it even a good idea, though, to start working on an EML nowadays? Our interviewees generally agree on the following: if your company is relatively large and can afford the costs of developing a quality game of this kind, it probably makes sense to at least consider it. By relatively large and cost-affording we mean the earlier mentioned 15 to 20 people working on the game for a solid year prior to its soft launch and the resources to then triple the team for live-ops and marketing. However, bear in mind that the risk/reward ratio is still not that fascinating.

Merge-2

So, what about Merge-2 games? Are there any important homogeneous subsets here to identify? There are indeed, and there are also two of them.

Firstly, there are the followers of Metacore Games’ mega hit Merge Mansion (let’s nickname these games MML for Merge Mansion-likes).

Secondly, there are games that are quite similar to Love & Pies. While this title is not the first to bring the specific game design concept to the market, it was certainly the first of its kind to become truly successful. We’ll have these games nicknamed LPL for Love & Pies-likes.

There is one very important difference between these two groups: their task systems. In MMLs, you progress along the metagame with every completed mini task: say, unlocking a leg of the storyline, a new decoration item, a piece of location, etc. In LPLs, you earn special soft currency for completing merging tasks, and the only way to advance along the metagame is to accumulate a certain amount of it.

This difference enables greater flexibility for LPL game design, both making issuing content more controllable and reducing the rate of its consumption (after all, there’s no endless supply of content, is there?). Besides, bear in mind that tasks (or quests) in Merge games, apart from being a goal-setting tool, are also a tool for removing unnecessary items that impede further play. And the high rate of content consumption typical for MMLs forces their game designers to reduce the drop of mergeable items from source objects, as well as increase the recharge time for the latter. At the end of the day, this can make the game very “greedy” and the game session disappointingly short.

Just like with Merge-3/5 games, there is a third group for Merge-2 games, too; identical to Merge-3s, it comprises all the titles that are different from the two sub-genres discussed above. And again, while there are quite a few of those, their performance is not impressive enough to provide any insights.

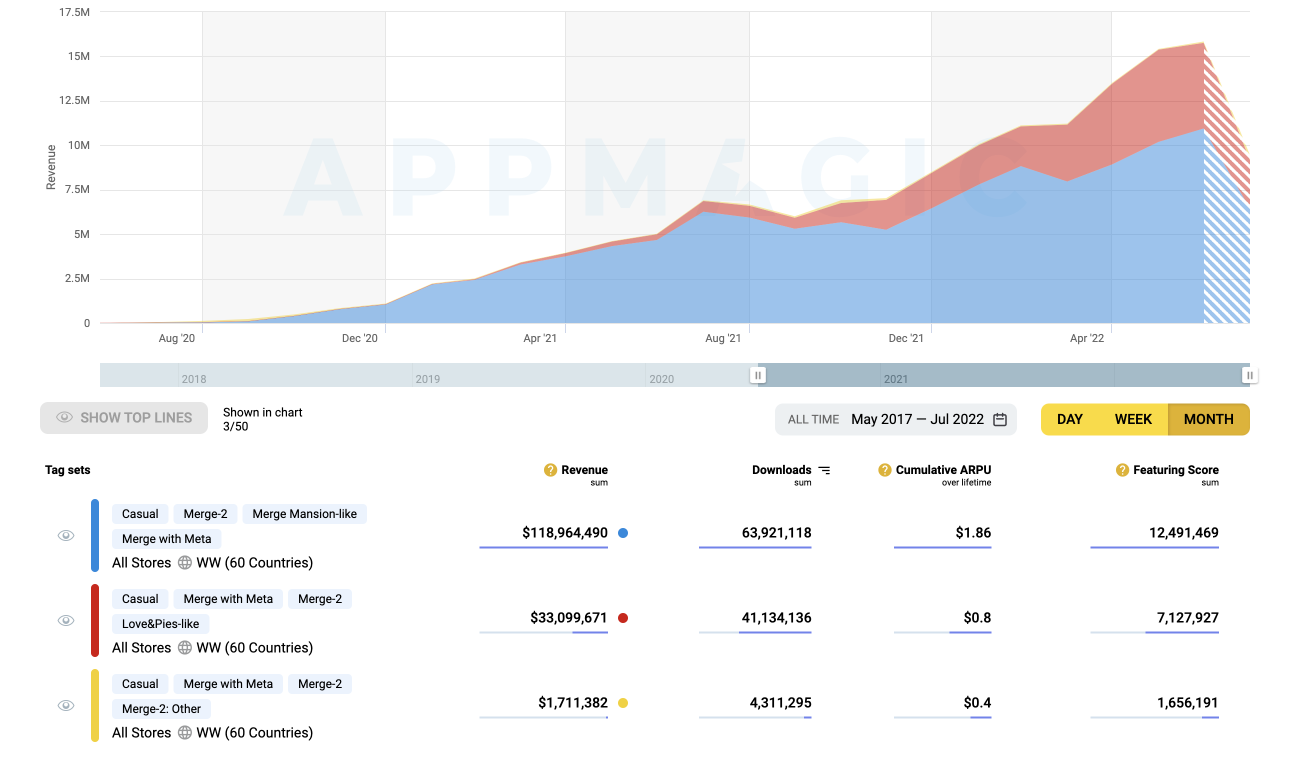

Click on the images to check the source data

As for the complexity of developing a typical Merge-2, our interviewees suggest a rather modest scale of things: they estimate that a team of 8 to 12 people can take the game from scratch to its soft launch in 6 to 9 months.

Merge-2: Merge Mansion-likes

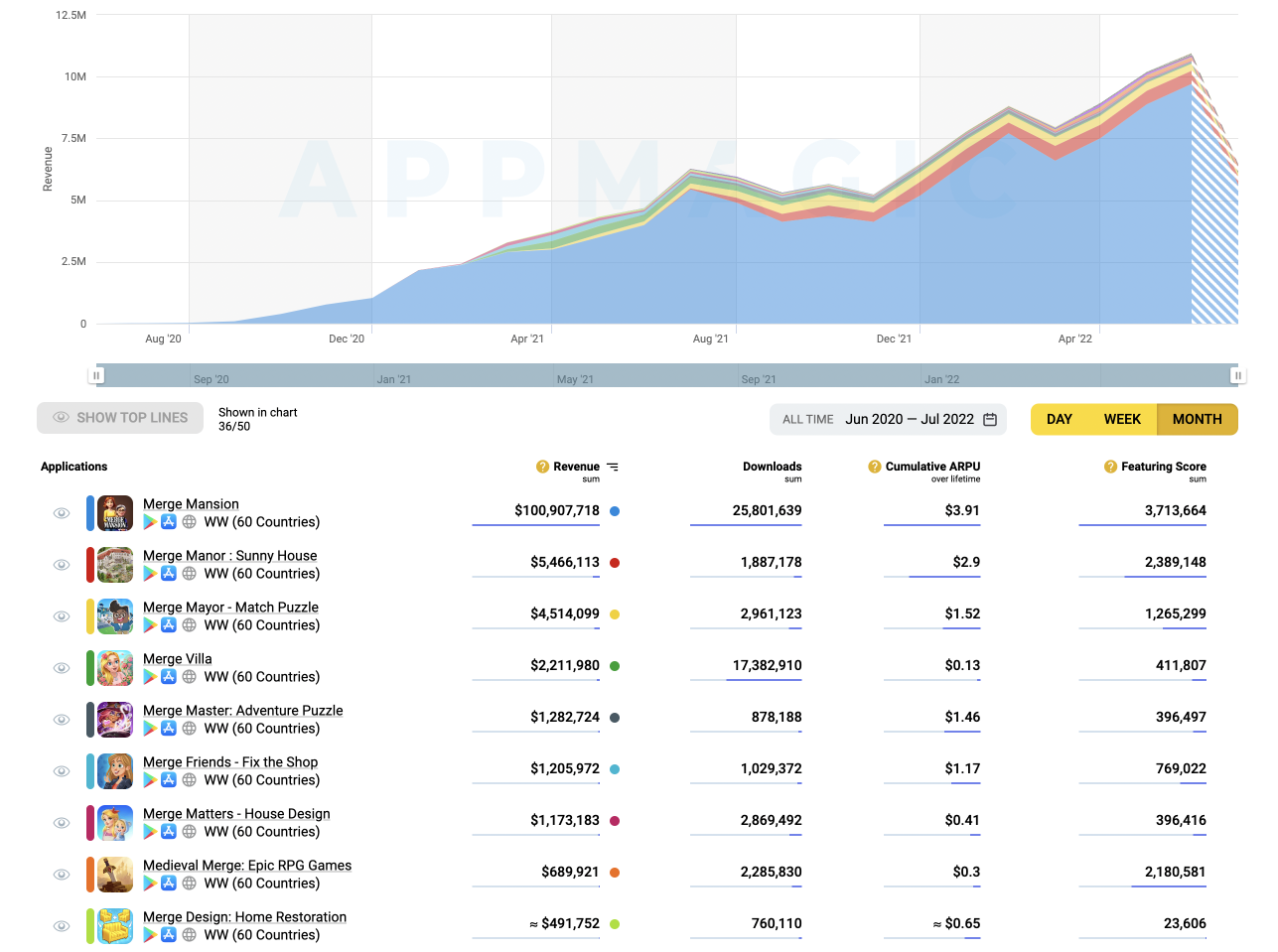

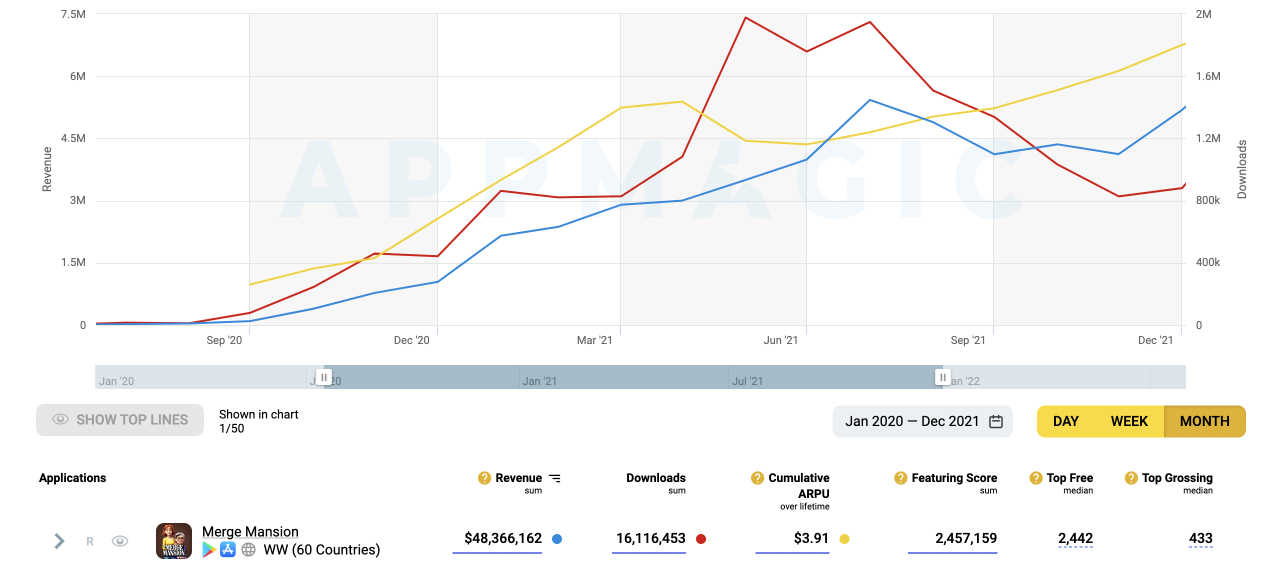

Merge Mansion itself is huuuge, and it reigns supreme over the market segment named after it:

Click on the images to check the source data

In this case, revenue is the key metric, so start by setting your eyes on the graph to the left.

Market data screams right at you, “Don’t even think about it!” In this sub-genre, hardly anyone is making any money but the mighty Merge Mansion itself. In fact, there were two Merge-2 games out there on the market released in 2021 by Merge Mansion’s developer Metacore themselves, and they demonstrated no success whatsoever despite the company’s seeming advantages of top expertise and financial leverage.

Given all this, Merge Mansion-likes as a sub-genre radiate about zero appeal for newcomers. One question remains though: how did the actual Merge Mansion become so popular, and how on earth does it grow?

That Very Merge Mansion

Rumor has it that Metacore invests astronomical amounts of money in user acquisition and that they might easily never get it back.

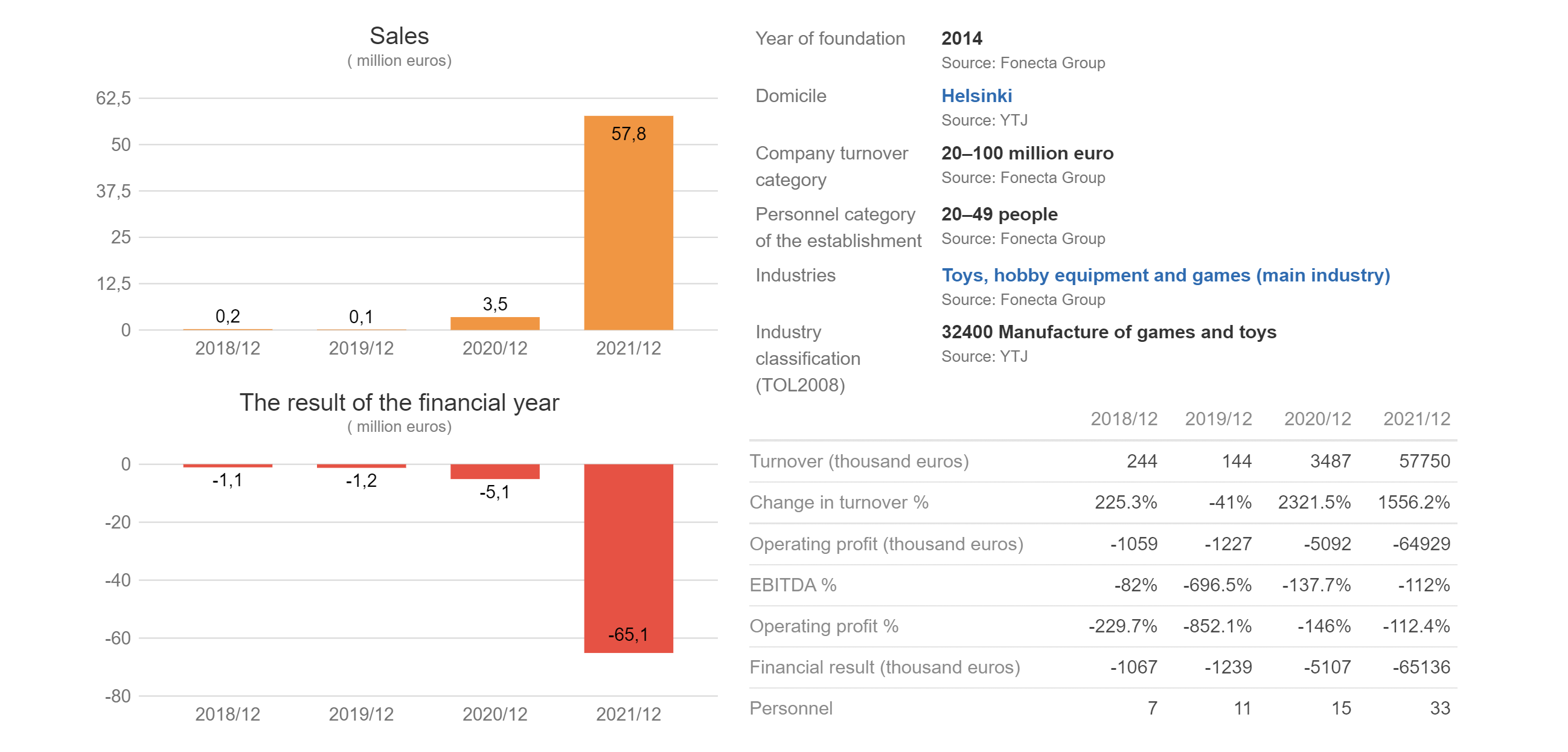

Is there any way to shed some light on the matter? Well, here’s a thought: conveniently enough, Finnish companies have their financial reports up on a special website where anyone can have a look at them. Data is available there for the latest four-year period.

Click on the image to check the source data

And we sneaked a peek! Metacore’s figures indicate that, during the time when Merge Mansion was in development (presumably 2019-2020), there were 11 to 15 employees in Metacore, who, in fact, were then working on several games at once and not exclusively on Merge Mansion.

Moreover, we see that in 2019, the company’s total expenses came up to €1.1М. Taking into consideration that in 2019 it also operated a few games already out on the market, a certain share of those €1.1М must have been spent on user acquisition.

We can’t do the same analysis for 2020, since Metacore started scaling Merge Mansion in late 2020, and their overall expenses skyrocketed; hence, we can’t make a good guess about their maximum budget cap on development that year. But we still see only 15 employees in the company by the end of 2020, when Merge Mansion has already went big.

This is notable and seemingly reliable evidence of a team you may need to produce a game of comparable caliber. Sure, there may have been some outsourcing, which is always an option. Nevertheless, the company’s total spending in 2019-2020 indicates that, even if there were any outsourcers involved, their participation wasn’t major.

However, Metacore’s personnel costs for Merge Mansion are outrageously low compared to marketing spend. The latter makes up about €130М for 2020 and 2021 combined. According to the very same financial reports, the game earned roughly €61M during that period.

In the same two years, the game pulled in 16М users (see graph below). Therefore, one user costs Metacore an average of €130М / €16М = €8.1 (or $8.3).

Click on the image to check the source data

The graph visualizes revenue figures approximated by AppMagic’s market intel tools. Numbers below the table refer to the same period of January 2020 to December 2021 to align with official reports.

Now, with AppMagic, we have the necessary tools for estimating iAP revenue. The company’s financial reports gave away the total revenue for the period ending December 2021. Just a basic calculation, and we have another benchmark for the game’s economics: its ad earnings constitute about 23% (€61M – €47M (or $48.3M) / €61M). Looks like a decent insight into the revenue structure of a top successful title of this genre.

According to all the data available to us by the day, the ROI (including revenue from organic traffic) for the first year of a user’s life (starting from the acquisition of said user) is roughly 70-80%. This is quite low, even for games with such an extended paying player lifetime as is typical for Match-3s.

However, if we take into account the cumulative revenue per download growth trend and the current metric’s value, along with the split between advertising and iAP revenue, it will be safe to infer that even the investment that seems wild to the outsider can return with a handsome margin. And this is a good moment to remind you that Metacore’s partner and investor is none other than Supercell—the business behind incredibly successful titles that went on to trigger the arrival of hundreds of followers. None of which has ever really made it comparably big. Those folks from Supercell must be onto something.

All in all, we believe the secret behind those revenue figures that are huge compared to competitors’ incomes is both about being the market pioneer and about truly daring (maybe even too daring) long-term marketing planning.

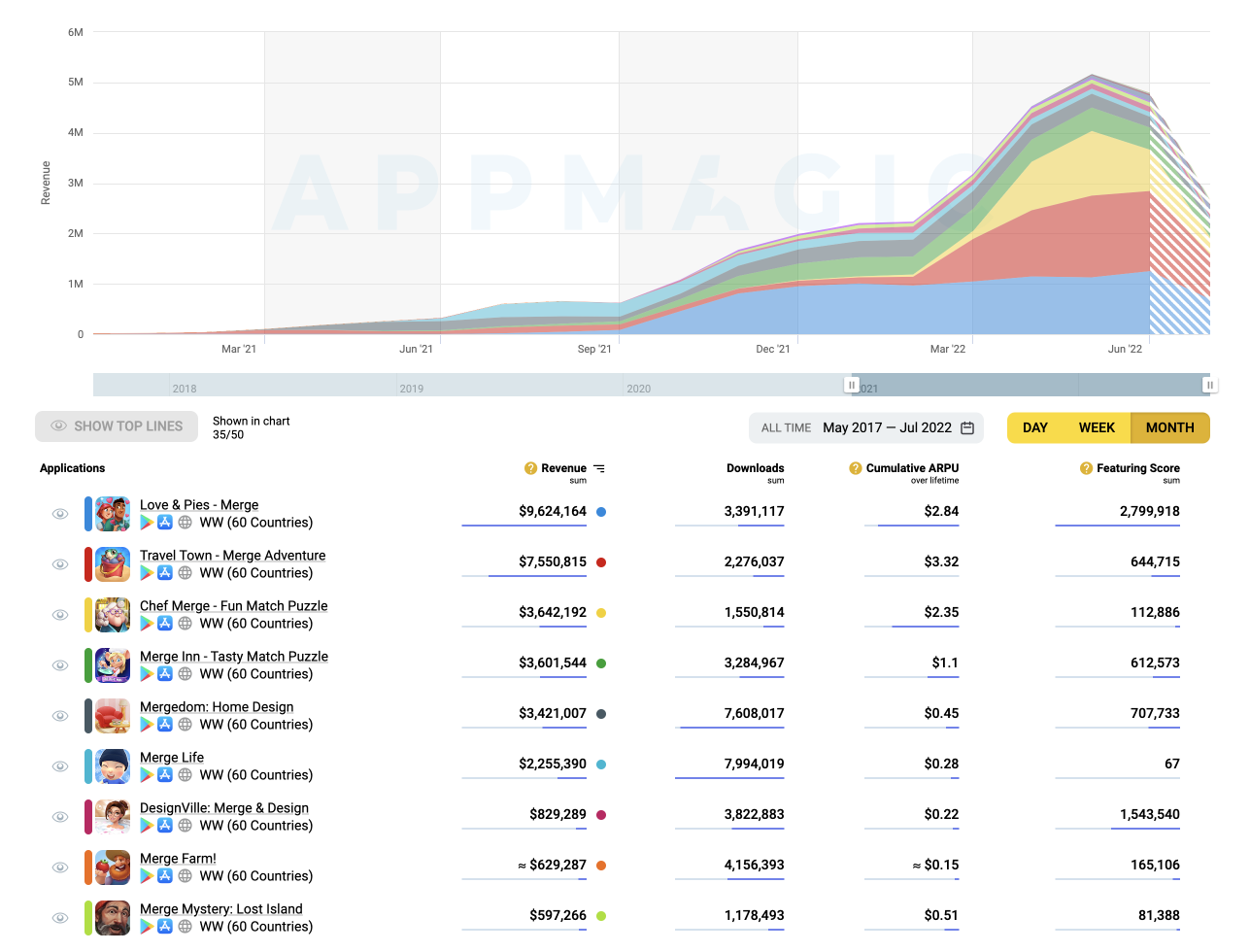

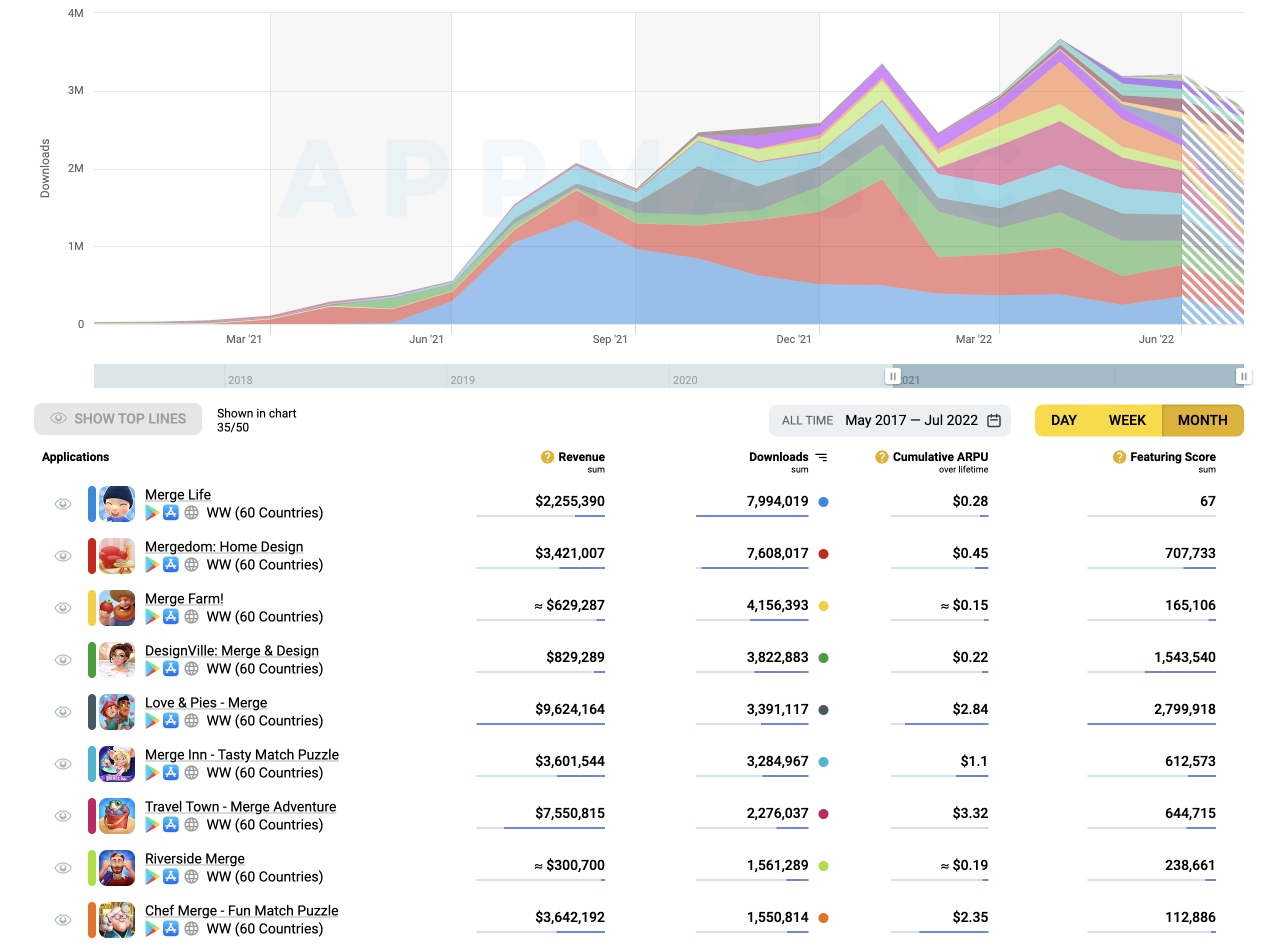

Merge-2: Love & Pies-likes

In this group, successful titles are not as twin-like as is the case with Merge-3 and MML games. Apps of this group are descendants of MMLs, similar in terms of how their in-game task system differs from that of Merge Mansion. In many other ways, they are quite diverse. This is actually significant, as it signals that the sub-genre is actively developing and that the market embraces innovation of sorts.

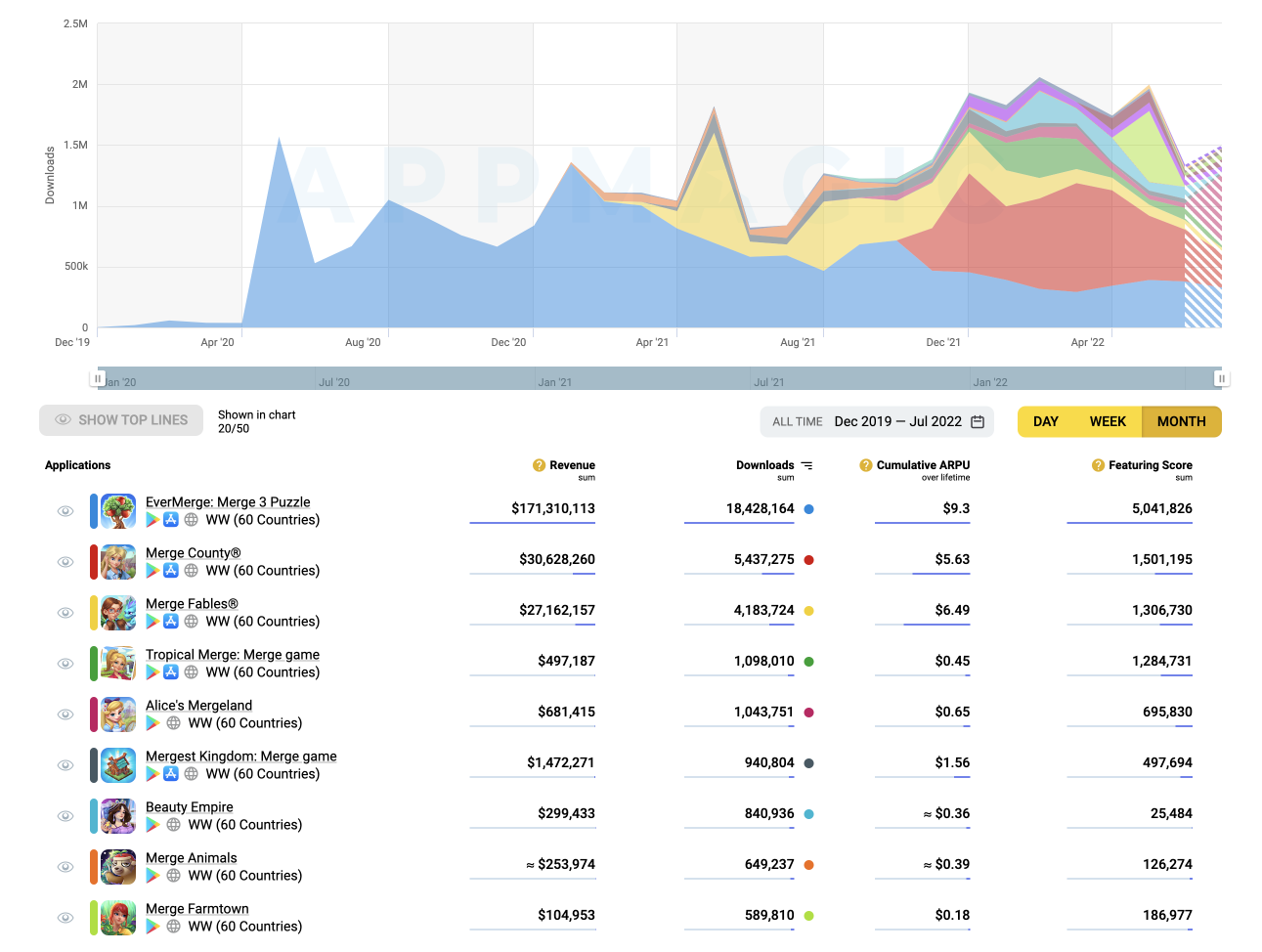

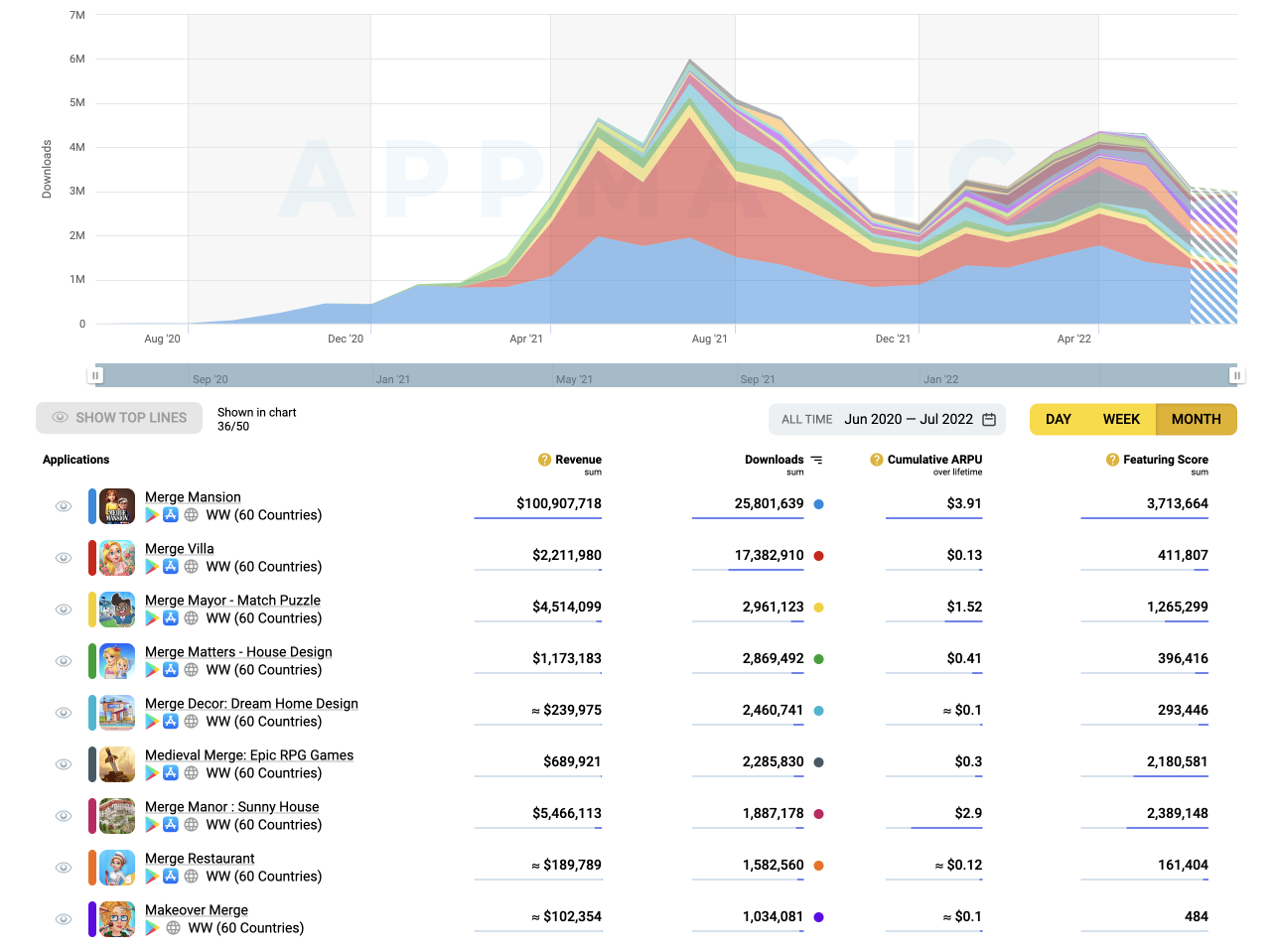

Click on the images to check the source data

At long last! Both graphs will matter equally in this case study: the iAP revenue and the downloads are both pieces of the puzzle. According to the feedback from our interviewees, iAA revenue for successful games of this type constitutes from 50% to 90% of their total income. Which means that we can take the iAP figures associated with the games of this sub-genre that also demonstrate high downloads numbers and multiply them by 2 to 10 times (depending on their iAP-based LTV and some heuristics) in order to estimate the size of their actual total income.

Question: what about all the Merge Mansion-likes — is it possible that a solid share of their revenue is generated by ads? Well, probably. However, overshadowed by the colossal revenue of the original Merge Mansion, all their followers are still earning literal drops in the ocean.

After all, the key difference between MMLs and LPLs — their task (quest) system design — stakes a convincing claim that all future successful descendants of MMLs and LPLs will employ the LPL’s task system, as it provides no disadvantages and multiple advantages.

Evolution of Love & Pies-likes

Despite the fact that LPLs still cannot deliver revenues (even including projected ad income) that are at all comparable to, say, Match-3 games, our interviewees believe that this very segment has the most potential of all the Merge games. By “all the games”, we only imply titles with Merge as core gameplay and not the eclectic hybrids mentioned earlier on in the article.

Here are a few advantages generally associated with the sub-genre:

- Extremely high early retention (with D1 retention of 50-60% a standard scenario, while some have witnessed up to 75% D1 at small-size early-stage tests);

- Wide target audience;

- Extensive variability range for the metagame. While the meta here is separated from core gameplay, like with Match-3s, it is easy to modify or replace altogether.

A Merge is traditionally seen as a game for a “predominantly female audience”, which means there is a tried and tested off-the-shelf collection of metagame types out there that you don’t even need to invent from scratch, including:

- Item and interior decoration;

- Makeover;

- Detective (narrative-based);

- Exploration/Adventure (like those you will find in contemporary mobile Farm games).

Nevertheless, you’ll see titles across mobile app stores that try hard to turn the target audience around and attract more men with alternative settings and metagame.

Actually, you can occasionally come across rather unorthodox solutions. For example, in Merge Neverland, the metagame is boosted by means of adding a super simple Tycoon: it is more of a venue for decorations than a real Tycoon, yet it provides some inspiration.

Genre’s downsides include the following:

- There is every reason to admit that Merge games’ target audience overlaps a lot with that of Match-3s, which drives the CPM through the roof even in cases when user acquisition is optimized for installs. Folks from AppQuantum named a few benchmarks around $100 to $150 for a US-based iOS user with install-optimized ad campaigns;

- Not the highest imaginable Day-30 retention of around 10%, which is lower than the Merge-3/5s with their Day-30 retention rate at about 15% (this all relating strictly to products that are actually successful, of course). This issue with long-term retention, however, can probably be solved rather nicely with spot-on metagame innovations.

There are other innovations in the genre, too. For example, introduction of several different playfields (not custom ones for events but permanent); adding source items (spawners) that can be “fed” some of the elements acquired via merging; and so on. Experimenting in this field is in full swing, and no clear winners or super hits have come out of it yet, but importantly they demonstrate that there is still room for innovation even when it comes to core gameplay.

What to keep in mind if you’re set on going merge

We asked our AppQuantum experts for some advice for smaller studios that are currently considering starting developing a Merge game or, maybe, are already doing that.

Here’s their key recommendation: design your game assuming a very long user lifetime of several years. This is the only way to earn back what you’ll spend on pricey user acquisition—and to then earn some more. And that implies a few aspects:

- Upon endgame, you’ll have a ton of balance issues that will arise from the fact that your player has sat on the same grid for a very long time; and that grid is packed with bits and pieces and whatnot that have built up over the years. For Merge-3 games, balancing this is frankly going to be hell;

- If you’re working on a Merge-2, you’ll need super strong expertise in ad monetization; by the way, every single one of our interviewees have mentioned this, and what they really mean is that it’s all harder than it might look;

- You will also need to deliver quality live-ops. Chances are, you won’t figure out what works and what doesn’t soon enough, if ever. So, collaborating with someone who already has relevant expertise in the field is a more than reasonable move.

Moreover, you will of course need a lot more to run a well-performing game and maximize your ROI, and that includes: deep personalization of iAP offers; strong product and marketing analytics; reliable user acquisition tools and partners; an ad creatives development team; etc. AppQuantum’s partners, for example, who publish games with them, get teams of 15 to 20 people assigned to their account to manage user acquisition and operations.

So then: once you’ve carried out your first trial UA and seen some inspiringly high D1 retention figures, do pop open that bottle of champagne — but bear in mind: your fight for success is just beginning.

In Conclusion

At the end of our discussion, we asked each of our interviewees: “Would you recommend your friend who owns a small or medium-sized game studio to start working on a Merge game?” They were all quite unanimous, and here’s their advice: “You might try going for a Merge-3 if you are a larger company. Meanwhile, Merge-2 definitely looks enticing today with regards to its risk/reward ratio; especially, if you invest into inventive metagame and monetization solutions, leveraging the genre’s great engagement.”

N.B.: Just to be clear: we are not recommending any investment strategies here! 😉

Do thorough preliminary research, test your concepts, and evaluate your target audience to make sure you’ve got it right. Only do the things you feel certain about.