Copyright God Mode: Is Russian law ready to combat cheat codes in video games?

The distribution of cheating software is a persistent problem faced by the video games industry. Despite the global nature of the challenge, most infringing torrent indexes are either operated/hosted from Russia or use Russian reverse proxies. In this article, Alena Kuzmina, a lawyer at Semenov&Pevzner, discusses the legal grounds on which the potential software cheating may be challenged under the Russian law.

Alena Kuzmina, Semenov&Pevzner

Generally speaking, cheating is defined as an unfair advantage of a player. From the legal and technical perspective, cheats are a type of software code designed to alter regular rules and functioning of the video game that allows the player to gain unfair advantage over others. At first, cheat codes were designed by video game developers for testing purposes. Some developers inject cheat codes as Easter eggs. Depending on the type of cheats, they can be harmless or pose a threat to the whole interactive entertainment industry. That explains why more and more countries are starting to find that cheating is not just wrong, but also illegal.

In Russia, though, copyright infringement is a persistent problem. While the intellectual property protection laws gradually evolve, Russia remains a thriving market for many illegal resources which severely damage legitimate content consumption. Due to its hostile piracy environment, Russia has become a regular in every notorious market list published yearly. This includes the latest Special 301 Report published by US Government, which puts Russia into the priority watch list due to the lack of robust copyright enforcement. And deservedly so. Most infringing illegal torrent indexes, which distribute illegal copies of video games, cheating (hacking) software, pirate modifications or unauthorized digital goods, are either operated/hosted from Russia or use Russian reverse proxies, as identified in the Notorious market list of 2020 (where I have counted at least 6 major resources out of 39 mentioned as “reportedly hosted from Russia”).

Some video game right holders have started shutting down non-compliant pirate resources which distributed illegal copies of video games. Top search engines operators, obliged by the right holders under Anti-Piracy Delisting Memorandum, now remove pirate links from search results, though this only concerns the motion picture industry. At this point, the root of the problem, namely, the investigation and identification of real operators hidden behind pirate platforms, has not yet been taken seriously. Operators of infamous torrent indexes, cheat code developers, affiliate and offshore hosting companies which induce the piracy distribution have not been properly prosecuted in Russia yet. All of this results in a severe and persistent international copyright problem, as users from around the world are accessing major pirate resources which originate from Russia.

When general take-down and stay-down letters to site operators or hosting providers do not have the expected impact, the question is whether Russian copyright laws have the necessary ammunition against cheat code developers? What is the situation with the case law around cheating software? Do Russian courts still believe that video games enforcement shall remain uncharted? Does the existing copyright regulation requires amendments to handle this crusade or maybe right holders just need to create more precedents?

Let us discuss the legal grounds on which the potential software cheating may be challenged under the Russian law.

Cheat codes overview

Aimbot, wallhack, burstfire, maphack — these are some of the most common cheat codes applied in shooters and RPGs. For multi-player games, cheating can severely damage the whole economy and in-game mechanics, especially when players obtain digital goods for real money.

Software hacks pose a major threat to the video game industry, since they make it possible to load pirated games on popular consoles and circumvent technical limitations. Hacking devices allow the technical protection of the game to be broken in order to jailbreak consoles and play pirated games.

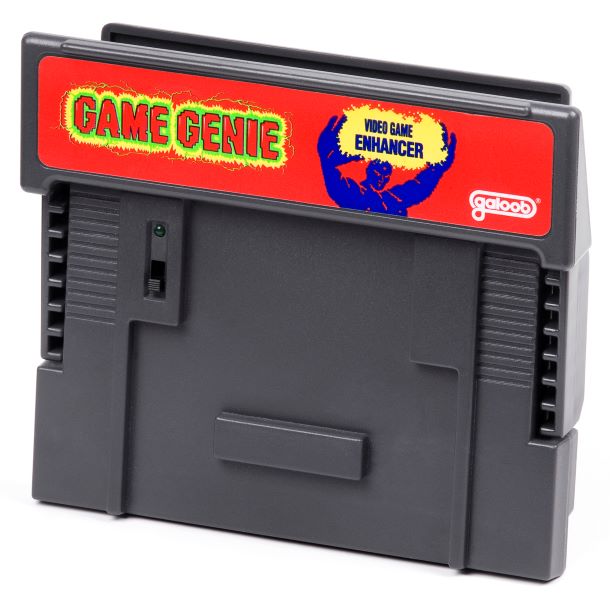

The early case law of the 90s around physical cheating devices was controversial at first. One of such cases involved a “game enhancer” called GameGenie developed by the UK company Codemasters and released by Galoob Toys (a major toy company in the US).

Game Genie for Super NES

GameGenie allowed to modify games on those classic Nintento devices (NES), so that the player could switch on the “god mode,” receive unlimited ammunition or skip levels (the player should connect NES to the GameGenie device). The original code of Nintendo games, however, has not been modified permanently by GameGenie. In a subsequent lawsuit against Galoob Toys, Nintendo alleged that GameGenie was a derivative work of the original game and thus constituted copyright infringement. However, the court concluded that a derivative work should have incorporated the original work in a “concrete and permanent form,” which wasn’t applicable to GameGenie. The alteration of the code was not permanent either, and the customers’ use of this device was also confirmed as fair use for personal pleasure and joy. The court did not find any financial damages to be awarded to Nintendo (Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo of America, Inc., 964 F.2d 965 (9th Cir. 1992)). Now, with the rise of DMCA and new technology things turned around – сourts have started to recognize cheats and hacks as illegal and malicious software.

Computer bots are another form of cheating – it’s the kind of software that helps build up character experience, virtual money without having to play the game. Bots are a type of robots that complete tedious tasks for users. Sometimes, bots circumvent access-control measures, anti-piracy and anti-cheating programs that developers install into the game. Bots have recently progressed in the way that their artificial intelligence resembles the actions of a real human.

Currently, most bots are developed exclusively for monetization purposes, which frequently damages the interactive entertainment market. For example, in World of Warcraft, bots can financially harm both the developer and players (and the case MDY vs Blizzard Entertainment proves the point). In this case, the bot Glider was developed and installed within WoW, which automatically completed beginner level tasks in the game. The trouble with this bot was that it did not alter the source code of WoW and was commercially independent from the game. Moreover, past Blizzard EULA documents did not prohibit bots at the time. Later EULA updates included the bot prohibition rules, but MDY made their bot to be untraceable. During the trial, the court held that Glider bot did not implicate Blizzard exclusive statutory rights and did not alter or copy the source code, hence the bot did not constitute copyright infringement (MDY INDUSTRIES, LLC v. BLIZZARD ENTERTAINMENT, INC., No. CV-06-2555-PHX-DGC (D. Ariz. Apr. 1, 2009)).

Gaming modifications, or mods, usually alter the code for functional and aesthetic purposes. Gamers often prefer to change their characters clothing, appearance, style, armour, vehicles and other items ‘just for fun.’ However, modifications still require alteration to the computer code. Some developers and platforms encourage users to create their own mods to games, for example, through the Steam Workshop, where video game developers grant the Steam permission to limited modifications. However, Steam Workshop mods are mostly general cosmetic accessories and do not radically change the entire game. The problem becomes serious when the code is hacked, reverse engineered, and the new modified version of the game is created (remember those well-known cases of Dota 2 and Counter-Strike?).

Copyright infringement in online video games often comes from unauthorized modification, bots, cheat codes and hacks. All of these manipulations with game codes are leveling up rapidly, which brings us to a question whether the current Russian law needs a speed hack to finish them?

Copyright regulation for online video games in Russia

Under the Civil Code of Russia, copyright protection extends to published and non-published original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium regardless of their quality and expression. Derivative works and complex works are also awarded protection. Copyright owners have various exclusive rights under Article 1270 of the Civil Code, such as the right to reproduce copies, make publicly available, produce derivate works, distribute, sell, expose, import, translate, modify, etc. Copyright protection extends to audiovisual works, software, databases, music, literature, design, etc.

There is no special regime for video games provided by the Russian copyright law. Video games are widely recognized as computer software by courts, which apply copyright protection rules stipulated under the Civil Code of Russia. Article 1261 provides that copyright protection shall be granted to all types of computer software (including OS and program systems) which are presented in any language, form or codes, including the source code.

However, most academic papers believe that a “complex work” regime should be applied to video games under Article 1240 of the Civil Code. This definition includes multiple IP protected works (audiovisual work, multimedia product, database, software etc.) and implies the ownership of the person or entity that organizes the creation of such work (provided that such person obtained permission from all authors of the included works). Moreover, several court cases between 2018-2020 classified video games under multimedia object regime, although did not provide any comprehensive dissent on this matter:

- Judgement of the IP Court dated November 2, 2020, case #A32-56176/2019;

- Judgement of the 17th Arbitrazh Court of Appeal dated September 22, 2020 case #A71-4683/2020;

- Judgement of the 18th Arbitrazh Court of Appeal dated April 10, 2019 case #A76-16733/2018;

- Judgement of the 15th Arbitrazh Court of Appeal dated June 26, 2020 case #A32-56176/2019.

A video game is not only about the code. It has music, script, sceneries, interactive elements, characters, plot, maps, and the whole alternative universes. Patents and trademarks are also an inseparable part of any video game. For example, Wargaming exclusively owns a patent for a display screen with graphical UI and a dynamic battle session matchmaking in a multiplayer game. Sony registered a patent for dynamic music creation in gaming. A game logo, user interface, virtual items, small parts of the game can be registered as trademarks (for example, the green Plumbob from The Sims series (trademark #395564). The complex structure of the video games raises the inevitable question of its qualification as a complex work since the copyright protection regime as well as ownership depend on this issue.

Plumbob from The Sims series

Russian intellectual property law grants copyright protection to original artistic works fixed in any tangible medium of expression. Such expression is broad and does not have a clear and precise definition. Concepts, ideas, principles, processes and methods cannot be subject to copyright protection.

Nevertheless, the copyright infringement for video games is mostly reviewed by courts from software/code protection perspective under Article 1262 of the Civil Code, in connection with the special form of video games expression. Moreover, some Russian courts still address gambling regulation to video games thus depriving them from any legal protection under Article 1062 of the Civil Code. In this case, the question is, whether cheat codes, hacks, mods and bots can be protected by current Russian copyright laws and whether this protection will suffice?

Remedies against cheaters

The very first remedy available for video game right holders against computer bots and cheat codes is a breach of End User License Agreement, which can be used against cheating players. Moreover, many video game developers implement anti-cheating technologies into their games which automatically detect cheaters and block their accounts (for example, Valve Anti-Cheat). Account blocking and server blocking (e.g. Source engine) also apply these anti-cheating methods. A couple of years ago, Microsoft implemented a TruePlay system which protects the game from most common types of cheating and monitors the behavior of players.

Most right holders stipulate liability provisions for cheating, bots and illegal modifications in End-User License agreements. Users are not permitted to use, develop, or distribute copies of the software, cheats, bots and mods (especially for commercial purposes) without a license. Under the Russian law, such agreements are enforceable and any breach can potentially be protected in court.

At the moment, the Russian case law has several disputes in connection with the breach of EULA (although initiated by gamers against video game right publishers for account blocking under Consumer Law):

- Judgement of the Lefortovo district court of Moscow dated June 9, 2015 case #2-1619/2015;

- Judgement of the Leninskiy Appeal Court of Kemerovo city dated April 26, 2013 case #11-59/2013;

- Judgement of the Basmanny district court of Moscow dated June 1, 2011 case #11-43/11.

The courts applied the breach of contract liability for gamers cheating and account hacking actions in online Free-to-play and MMORPG games and confirmed that these actions constitute the breach of EULAs between publishers and gamers.

Apart from civil cases, a couple of precedential criminal cases against cheaters were initiated in Russia. In 2014, an individual V.V. Petrov was sentenced to probation under Articles 272 and 146 of the Criminal Code of Russia for copyright infringement an unlawful access to software for hacking an online game King of Kings 3, creating and selling the virtual items to other players (Judgement of the Khoroshevskiy district court of Moscow dated June 17, 2014 case #1-260/14). In September 2021, the police started to investigate the creators of Worlds of Warships bots and cheat codes CyberTank and Hags (which distribute bots which earned virtual currency in Wargaming’s World of Tanks).

Boss level: cheat code developers

Cheat code developers are being targeted internationally by video game right holders. In 2019, Pokemon Go developer Niantic filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against company Global++ for distributing cheat codes and hacks. Parties reached a settlement whereby Global++ was ordered to pay damages of $5 million and prohibited to develop, sell or commercially distribute the cheat software.

In January 2021 Riot Games and Bungie filed lawsuits against cheat maker GatorCheats for copyright infringement in Valorant and Destiny 2. Plaintiffs argued copyright infringement and violations of the anti-circumvention provisions of the DMCA. In less than two weeks, the defendant agreed to pay $2 million damages and was imposed a permanent injunction which prohibits to create, sell and distribute the cheating software in the future.

GatorCheats website prior to shutdown

In the EU and US jurisdictions, right holders have started to chase cheat code creators (individuals and companies). For example, Epic Games obtained injunctions against two individuals for making and using cheating software in Fortnite. Blizzard Entertainment won the copyright lawsuit against German creator of software bots and cheats that allow players to cheat in World of Warcraft and Overwatch titles, e.g. to see through walls or collect items instead. Blizzard brought proceedings in which it alleged that Bossland’s cheat codes development and promotion not only infringed EULA, but also induced players to breach the license terms with Blizzard (Blizzard Entertainment Inc. v Bossland GmbH, 8:16-cv-01236-DOC-KES).

Administrative and criminal measures are taking place in Asian countries. For example, in 2017, South Korea adopted a law which even provided criminal penalties for cheat software developers. Even users can face prison sentences of up to 5 years or a fine of $49 000. In China, 10 people were arrested by police in March 2021 for selling a cheat-based subscription program for Overwatch and Call of Duty Mobile.

Indeed, a situation becomes more complex when we deal with the original creator of the cheating programs. It is not entirely clear whether the cheat maker infringes copyright to the video game in general under the Russian law.

First of all, given the nature of the video games protection rules in Russia, cheat codes, bots and mods can be reviewed from an illegal software modification angle. Under Article 1270 of the Civil Code of Russia, software modification shall be authorized by right holder. Case law has a broad interpretation for modification, and the right holder needs to prove the fact of software modification. The usage of a unique source code and modification of the functions (fully or partially) of the software can qualify as software modification. When arguing for illegal modification, creation of the adaptation based on the original as well as general resemblances between the original and modified software are most important points to prove in court.

However, under Article 1280 of the Civil Code of Russia, it is not considered infringement for the owner of a copy to:

- use the program for utilization purposes,

- make or authorize the reproduction of another copy or adaptation provided that it is an essential step in the utilization of the program and that such new copy is for archival purposes only and the copies are destroyed in the event that the possession of the computer program ceases,

- research and test the functions of the program solely for utilization lawful purposes. The law does not allow these exceptions to be used for commercial purposes.

Apart from the exceptions stipulated on the legislative level, there are several copyright doctrines applied by Russian courts which do not allow the works to be protected by copyright laws. First of all, the dichotomy of the idea and expression depend on the “scenes a faire” doctrine, a principle in which certain elements of copyright work cannot be protected because they are customary or mandatory for this type of work (for example, the concept of the Normandy beach in Call of Duty WWII cannot be protected itself, but the specific code for the original rendering of the Normandy Beach scene for this game is protected).

Secondly, the merger doctrine, which does not provide copyright protection to ideas that can only be articulated in a limited number of ways. With respect to software, when specific parts of the code that were previously protected under copyright are the only and essential means of achieving a certain goal, the work can be copied legally.

Thirdly, game mechanics cannot be protected under copyright law. For example, the concept of battle royale games (Fortnite and PUBG) cannot be enforced in courts of law. In Russia, this principle was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in a lawsuit filed by the French board game developer Asmodee Group against Cosmodrome Games over association games Dixit and Imaginarium (Decision of the Arbitrazh Court of Moscow dated August 28, 2018 case #A40-176122/17-51-1615).

Even though these doctrines are mostly applied by court of common law, Russian courts also address similar doctrines when questioning the level of copyright protection to a certain work:

- Resolution of the IP Court of Russia dated March 28, 2017 #C-01-78/2017 case #A56-73596/2015;

- Resolution of the 9th Court of Appeal dated June 24, 2019 #09АП-28070/2019-ГК case #A40-60319/2018.

That said, computer bots, cheat codes and mods can be qualified as infringing manipulations under the Russian law when such programs affect the source code. This can be done via reverse engineering, i.e. allowing the programmer to use the deciphered code to create different algorithms for duplicating the program.

Another option for online games to be protected against cheat codes is the Russian site blocking law provisions, which allow a right holder to obtain a content-removal injunction even against the most non-compliant resources and have them shut down permanently. Under Russian Anti-Piracy Law, a right holder can apply to the Moscow City Court for the content-removal preliminary injunction. Upon obtaining the preliminary injunction, Roskomnadzor, an administrative body responsible for anti-piracy law enforcement, notifies the hosting provider about the infringement. These site blocking provisions include:

- Federal Law #187-FZ dated July 2, 2013 “On amendments to separate intellectual property rights laws in Russia”;

- Federal Law #364-FZ dated November 24, 2014 ‘On amendments to Civil Procedural Code of the Russian Federation and to Federal Law ‘On amendments to Federal Law “On Information, IT and Protection of Information”;

- Federal Law #1560-FZ dated July 1, 2017 “On amendments to Federal Law ‘On Information, IT and Protection of Information.”

The hosting provider shall then forward the notice to the website operator. Finally, the website operator is obliged to remove the illegal copy of the video game, otherwise Roskomnadzor orders ISPs to block the non-compliant website temporarily.

After that, right holder has 15 days to file the statement of claim with the Moscow City Court so that the injunction would remain “permanent.”

Upon obtaining the final first Moscow City Court order against a particular infringing website, the right holder can apply for permanent website blocking in case the website repeatedly infringes any other video game owned by the same right holder.

The blocking law applies to standard web resources as well as to installed software and apps. Since the amendments brought in 2020, any mobile app can be subject to blocking for copyright infringement (with exceptions as to permanent blocking rules’ current inapplicability to mobile apps). This law compels app stores to remove infringing applications for copyright infringement (as previously the law could only tackle ordinary torrent indexing sites and streaming portals, and the former regulation was inapplicable to pirate software apps) (Federal Law as of June 8 2020 #177-FZ “On amendments to Federal Law ‘On Information, Information Technologies and Protection of Information.’”

Cheat codes, bots, hacks and other unfair mechanisms pose a threat to the video game industry as they negatively impact developers leading to great financial losses. Russian case law against cheaters needs to be strongly improved, and this is a chance for video game developers to expand the case law. Even though the law does not provide specific rules against cheat codes, the existing regulation in Russian law (anti-piracy and blocking laws, illegal modifications and adaptation rules, contractual law and even criminal prosecution) applied comprehensively and consistently by right holders against the source of the problem (cheat codes developers) may become that healing spell for the legal content consumption.

About the author: Alena Kuzmina is a lawyer at Semenov&Pevzner. Prior to joining the team, she was head of legal at leading Russian IT and anti-piracy company. She graduated from the Higher School of Economics. Her experience includes advising leading Hollywood studios, including Disney Enterprises Inc. and Warner Bros.