Eliza developer Matthew Burns on stress, choices that matter, and language of games

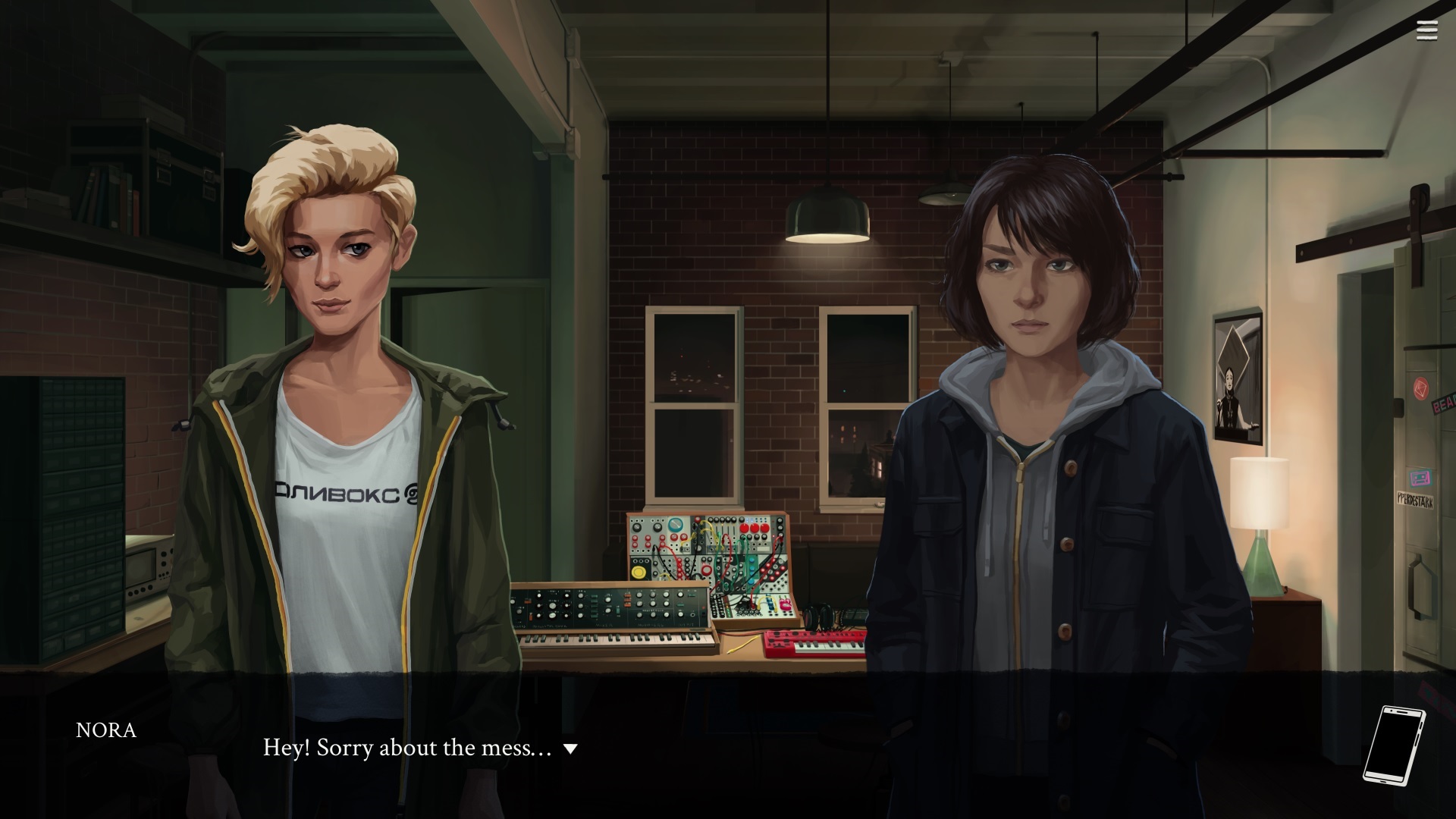

Eliza is the latest title from Zachtronics that took everyone by surprise. In contrast to the programming puzzle games the studio is famous for, Eliza is a visual novel about an AI counseling program, the people who develop it, and the people who use it.

You might want to check out a small review of the game that we posted earlier.

Good folks at GOG.com put us in touch with Matthew Seiji Burns, the man who wrote Eliza, composed the music for the game and is otherwise responsible for its production.

Matthew Seiji Burns, writer, composer, and game developer.

GWO: Matthew, before joining Zachtronics you worked at Bungie, Treyarch, and 343 Industries. What is it that you did?

Matthew: When I worked at these studios I was a producer. That meant creating production plans, making sure all the right assets were created in the right order and on schedule, ensuring we had enough staff, and so on. I concentrated on several areas including design, animation, and audio.

GWO: You also worked at a games research lab at the University of Washington. What was your role?

Matthew: I worked at a games research lab called the Center for Game Science. This role was much like the producer role I held previously; it involved the day-to-day management of this research group. The work was very interesting and I greatly enjoyed my time there. In particular, we investigated the way computers and humans can combine their different problem-solving approaches to tackle complex problems in science like protein folding.

GWO: Of all studios out there, why did you join Zachtronics after going indie? Not exactly a go-to studio for story-driven games. Or so it seems.

Matthew: It’s true that Zachtronics isn’t the first studio you’d think of when it comes to story. However, that was part of the appeal to me. I’m not interested in “telling stories” for their own sake; for me, the stories have to connect to something in order to make them real. All of Zach’s games start with something grounded, even when they take place in a fantasy world [Zach Barth, founder and creative director at Zachtronics—Ed.]. Also, even though it might not be apparent at first glance, Zach takes story seriously and considers it from the beginning of every project— even the ones about assembly language programming. He wants to understand why players would be performing these actions before he asks them to do it. Since most of what you do in a typical Zachtronics game is manipulate abstract symbols, there needs to be some kind of meaning eventually.

GWO: Where does Eliza stand in the lineup of Zachtronics titles?

Matthew: Eliza is a unique experiment for the studio, but people familiar with the stories in other Zachtronics games might see there’s more in common with Eliza than first appearances would suggest. All of the team’s games, starting from SpaceChem in 2011 and running through games like Infinifactory, Opus Magnum, and EXAPUNKS, explore the consequences and implications of the engineering work its players perform. In that respect, Eliza could be seen as an expansion and deepening of the studio’s worldview, rather than a reversal.

GWO: Eliza feels almost painfully personal. One of its themes is career burnout. You also wrote a book called “Surviving the game industry.” Could you tell us about specific experiences you had back in your AAA days that led to a burnout?

Matthew: While they were not universally bad, I definitely had some unfortunate experiences. My physical and mental health were negatively affected by cultures of stress and crunch at multiple places I worked. In fact, one of the studios I worked at years ago was recently in the news over allegations about its crunch culture. Looking back, I feel that maybe I should have taken a stronger stand against it. But I was young and wanted to be seen as a good team member, so I let it happen.

GWO: Counseling sessions account for much of the story and gameplay. Any of your personal experience here, if that’s an ok thing to ask?

Matthew: That’s fine — it would be shocking if I didn’t have this experience, right? My personal experience with counseling does inform the game in a few ways. One is the overall structure of the session. The counselor starts with some small talk about the weather and then segues into weightier topics. Another is how once you get started talking about yourself, it’s easy to keep going when the other person prompts you. I guess I should also mention that my experience with person-to-person counseling has been overall a positive one.

GWO: You said that while researching for the game, you conducted a number of interviews. One was with a counselor. How did you approach people about those interviews?

Matthew: I was interested to find out more about the methodologies, the way counselors themselves are trained, and how they think about their work. I was lucky to be able to talk to someone who was very open about their work while also being honest about its limitations.

GWO: Any discoveries from talking to these people that informed any aspects of the game?

Matthew: There were two things I learned that became represented in the game. One was that mental health practitioners love numbers. For example you might have to answer the question, “How do you feel, on a scale from 1-10?” You might have to answer this question over and over, every time you see your therapist, or at regular intervals throughout the day. Putting your mood into a number is a strange concept if you think about it, so it became something discussed in the game. The second thing was looking at a manual for practitioners of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and realizing that many interactions with even human therapists are scripted, at least in a loose way.

GWO: Eliza‘s narrative does not start to branch out until very late into the game. The gameplay is rather restrictive in terms of choices you can make. Could you explain your thinking behind this?

Matthew: If a game started and your character had a choice right off the bat, say to go outside or stay home, it wouldn’t mean anything and you would pick almost at random. Or you would pick what you, yourself, wanted to do at that time. What a long period of linearity does is allow me to set up a more complicated situation. Maybe your character doesn’t usually like to go outside, but today you are considering it because your father is angry with you. Suddenly this choice becomes more interesting when there’s more context for it— more character, more history. So I wanted to use this kind of structure where I spend a lot of time setting up one very complex, interesting choice, instead of providing a thousand small choices that do not ultimately matter, which is the route some games take.

GWO: Voice acting is fantastic in Eliza. How did you go about finding the voice talent for the game?

Matthew: Thank you! We held open auditions for each character and received over 1,200 submissions, an overwhelming number. It took the casting director, Khris Brown, and I many days to listen to them all and many more days agonizing over our final picks. For some of the characters I listened to them while playing some of the music I was working on for the game at the same time, to try to get the feeling of what it would be like in the final product.

GWO: One of inspirations for Eliza was a virtual therapist demo for those potentially having PTSD. Do you know what became of it?

Matthew: The specific program I saw the demo of is no longer funded, but the technologies used to power it still live on, both at the university that created it and in the larger research community. Additionally, large tech companies also continue these lines of research, such as Amazon’s documented interest in detecting your mood from your voice.

GWO: What were the challenges and discoveries in transitioning from a Twine interactive storytelling you did before to a visual novel?

Matthew: Ultimately, because of the artists and actors I was able to work with, it was a more collaborative process than those previous projects. For example, my Twine games had very little in the way of visual imagery. So doing this project meant considering some new things such as, what do these characters look like? What clothes do they wear, and what does that say about them? With text you can leave a character very nebulous, or define them by one small observation. But when you are portraying them full-on, every choice that goes into the portrayal adds to the character, and the artists contributed their own ideas for dress, posture, expression, and so on. The same goes for actors. Writing something to be read is different than writing something to be performed, so I had to adapt to a somewhat different style. Actors add so much information to a character with their performance, so often times you can leave things to them, instead of trying to push everything through the text.

GWO: Is there a fundamental difference for you between writing games and writing short stories?

Matthew: Not really… in fact, I would go so far as to say that for me, there isn’t even a fundamental difference between writing text or writing music. There are plenty of technical differences, and the language is different, but at the very bottom they’re basically the same activity.

GWO: The game is as much about therapy as it is about talking and listening. On some level, Eliza feels like the extension of your text-only game Apology Simulator. And before that, you wrote about depicting human interaction in Gone Home. Is it accurate to say that human interaction is the overarching theme in your works?

Matthew: I’m not the type of writer to boldly declare my own overarching themes, but I think one could make a reasonable argument that this was the case!

GWO: You wrote on your blog that “the time I spent hashing out my thoughts on games here helped me find my positions, develop my theory.” Do you think you could talk a little bit about that theory?

Matthew: Here’s the short version: When most people say “games” they think of discrete products— rows of cases on a shelf in a store, or a set of entries in someone’s Steam library. To me, though, games are not individual units any more than “architecture” is a set of buildings or “philosophy” is a pile of books.The buildings you see are the result of the process of architecture; the pile of books is the outflow of the activity of philosophy. In the same way, games to me means the set of technologies, tools, and techniques we use to make them. They are a language, a grammar — one we can use to entertain, educate, and realize works of true artistic expression.

GWO: Matthew, thank you very much for the interview. Good luck to you and Zach in your pursuit of those clandestine R&D objectives at Zachtronics! You guys are one of a kind.