How to turn morality into game mechanic using Dishonored, Rimworld, and Crusader Kings as examples

Morality is a great tool for game designers that adds depth and complexity to player decisions. So how do we transform morality into game mechanics? Let’s take a look at a few games that have done this well.

Author: Andrei Medvedev, game designer

Author: Andrei Medvedev, game designer

It is rare to find a compelling and fun moral choice in real life, while video games allow for safe exploration. No wonder the phrase “tough mopal choices with consequences” has occupied marketing for so long.

We need it.

For the purposes of this article, let’s define morality as follows: “Morality is a subjective perception of certain behaviour as ‘good’ or ‘bad’.” Helping people in need is good. Killing innocents is bad.

Now let’s dive in.

What are the types of morality in video games?

1. Games with no morality — usually abstract and hypercasual titles like Tetris.

2. Games where morality is not a concern. In NFS: Most Wanted, the player races around the city and blows up cops. Technically, this is immoral. But the game is not about morality, so we don’t even think about it. We’re just having fun.

3. Games that have morality but don’t give players a moral choice. To make the player feel good about themselves, morality is often one-sided in such titles. However, there are exceptions.

In Call of Duty, the player kills a lot of people. But they’re the bad guys, so it’s fine. When there IS a mission where we have to shoot good guys, it’s a striking exception. The game confronts players about the moral aspect of their actions.

Arguably the most controversial mission in the entire series, it makes the player participate in a terrorist attack on a civilian airport

At the other end of the spectrum are games with an exclusively negative moral code. The player does bad things and is aware of it. These types of games include Hatred and Hotline Miami.

Certainly, there are also games with a “gray” morality that depict both good and bad things (e.g. The Last of Us series). Still, they don’t offer the player any choices in the matter.

4. Games where moral choices are emergent. They arise naturally as a result of game mechanics interactions, but they’re not designed as full-fledged mechanics.

In XCOM, the player might find themselves in a situation where they must sacrifice one soldier to save the rest of the squad. There is no “Heroic sacrifice” button that saves the squad at the cost of one life, so the choice emerges in the player’s mind, and not in the game mechanics.

5. Games where developers rely on moral choice to enhance the overall experience. Based on what game elements they affect, I divide them into two categories: storytelling moral choices and gameplay moral choices.

The difference between storytelling and gameplay moral choices

Storytelling moral choices

Storytelling moral choice only influences the plot. It serves more as a tool for screenwriting than game design. So we will only touch upon it briefly.

Gameplay-wise, the outcome of the Bloody Baron questline in The Witcher 3 doesn’t matter. Geralt will continue to slash enemies in third-person RPG-style combat. The moral choice will not make the player change their gear from the School of the Griffin to the School of the Bear. Thus, The Witcher contains a storytelling moral choice.

Making the “right” moral decisions often results in missing out on certain parts of the game, such as when the player chooses to spare the enemy or to resolve a conflict diplomatically. This usually skips a battle, but doesn’t really change the game mechanics. This only changes the sequence of events, i.e. the plot.

Mass Effect is another example of this. It doesn’t matter who survives in the end: the Geth, the Quarians, or both. Choosing between Renegade or Paragon options won’t force the player to change Shepard into a melee fighter, nor will it unlock additional mechanics. The only changes will be to the plot and visuals elements.

The only things that can affect gameplay are when Shepard’s decisions make one of their companions leave or when a squad member’s abilities become locked as a result of their loyalty missions in Mass Effect 2.

However, the changes that affect the player’s party are relatively minor and can be found in many story-driven RPGs.

In Divinity Original Sin II, the player can unleash a deadly gas into a populous city, which will immediately make some companions hostile. There is no way to get them back, meaning you will lose all their abilities and items and will have to play with a smaller party.

The moment you unleash the deathfog onto the city you companions turn on you for this evil act

Gameplay moral choices

Gameplay moral choices change game mechanics in a major way and affect the playstyle. So let’s take a look at a couple of games where morality forces the player to choose between different playstyles.

Rimworld

Developed by Ludeon Studios, Rimworld is a sci-fi colony sim and a spiritual successor to Dwarf Fortress. The game includes some options that are morally dubious at best, including organ harvesting, slavery, drug dealing, executions, prisoner gladiator battles, and the use of inhumane weapons.

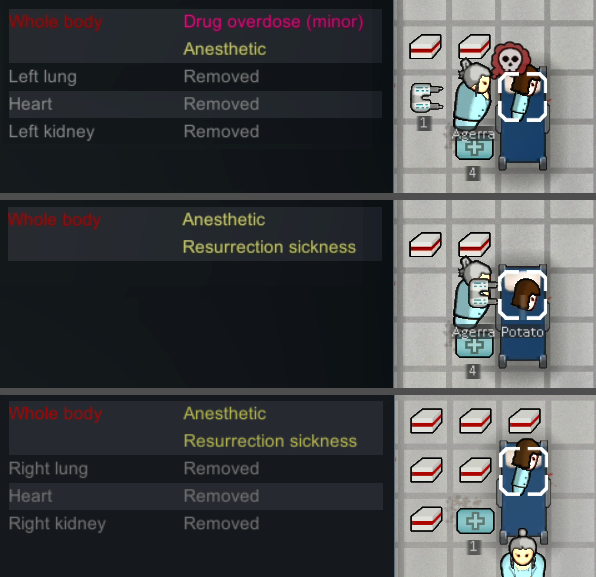

Performing immoral actions in Rimworld provides clear gameplay benefits. Harvested organs can be transplanted into sick colonists, making them more effective, or sold for a good price. Drugs can be easily produced and sold for high prices, giving temporary buffs to colonists. Slaves are cheap to maintain, and inhumane weapons can be more effective in combat.

It’s worth noting that players can achieve their goals without selling their souls to the devil, although it may require more effort. Organs can be synthesized, but you’ll need resources and research. You can sell other luxury items instead of drugs, but at less profit. Regular colonists can be used instead of slaves, but they are more expensive to maintain.

So why would a player choose a “good” playthrough when it is objectively worse from a gameplay-wise?

A person was extracted from a cryptosleep casket and their organs were harvested. Brutal

Mood is a balancing mechanic in this moral conundrum. Colonists in a good mood are effective and can gain inspiration, while colonists in a bad mood are prone to mental breakdowns, a negative debuff that puts them out of commission and can harm the colony.

Most “evil deeds” in the base game reduce colonists’ mood, as nobody wants to be the bad guy. The only exception are psychopaths, who are immune to evil moodlets.

Rimworld’s morality mechanic matches the definition we gave in the beginning. It’s the subjective thoughts of the colonists about their actions.

Negative moodlets for butchering humans. One is personal and the other is colony-wide

Historically, different cultures had different moral codes. For Romans to have slaves was completely normal, an unacceptable act in modern days. And this subjectivity is reflected in the game through the Ideology DLC.

In Ideology, the player creates a set of rules, known as precepts, to regulate colonists’ opinions about various actions. The stance of these precepts can range from “unacceptable” to “required”. For example, colonists who view agriculture as unacceptable will have negative moodlets when planting rice. Conversely, colonists requiring cannibalism will be happy to consume human flesh, but unhappy to eat anything else.

Ideology affects many aspects of the game and gives players precise control over the colonists’ morality. Colonists with different ideologies may clash, leading to social conflicts and even injuries.

The morality mechanic in Rimworld is a powerful story-generation tool that helps reinforce the narrative of survival and society-building. Players who choose to follow different morality codes will have different playstyles.

Interestingly, the player doesn’t have an avatar in the game, so they rarely view decisions through their own morality. This is similar to playing an RPG where decisions are made through the lense of the colony. This enhances the player’s ability to try different playstyles, regardless of their personal views, and increases replayability.

In Ideology menu, the player can see all the precepts. This ideology prohibits drugs and prostheses, but makes you want to feel pain and eat human meat

Crusader Kings 3

Another game with full morality simulation is Crusader Kings 3, a grand-strategy title by Paradox Interactive where you take on the role of a medieval monarch. You follow their life from ascension to the throne to death, participating in various events, creating a family, and gathering diseases along the way.

The morality mechanic here is quite similar to that in Rimworld. The monarch has a stress meter that increases when they perform actions that they consider immoral. Kind characters experience stress from murder, while honest characters experience stress from lying. Conversely, cruel characters are less stressed by murder and dishonest characters by lying.

Stress management is a crucial aspect of the game. When stress reaches one of three critical levels, the character experiences a mental breakdown, which can result in negative traits or make them waste resources. At the highest level, the character may even die of a heart attack, making it vital to play to your character’s traits.

If this character goes through with this assassination, he will gain stress because of the combination of his traits

Your actions also affect other characters’ opinions of you. Executing someone’s relative will cause their family to hate you, jailing people without cause will result in a decrease in opinion due to tyranny, and siring a bastard will make your wife dislike you.

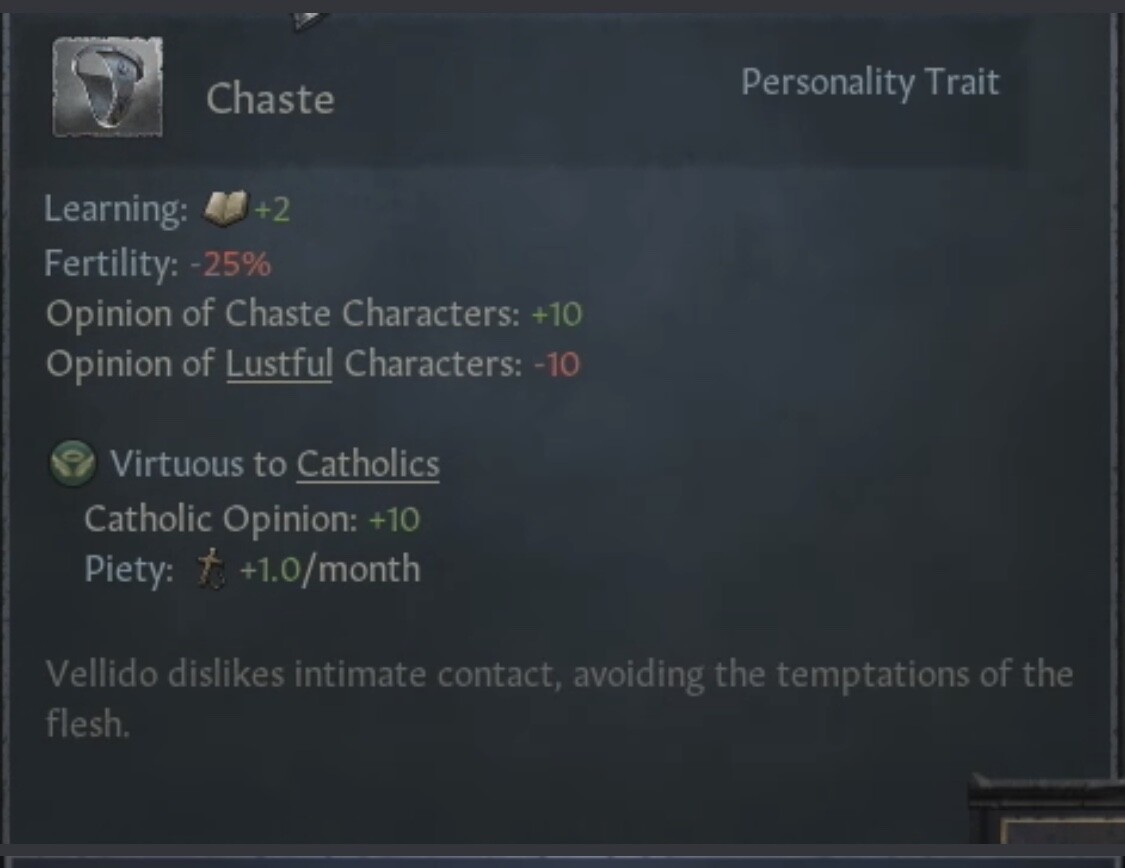

Just having certain traits can affect how people feel about you. Opinion matters a lot in CK3. Enemies will plot to kill you; enraged vassals will rebel against you, etc.

Chaste characters like other chaster characters and dislike the lustful ones

We can call this mechanic “individual morality”, where each character has their own set of traits and opinions about you and your actions. A unique moral code, if you will.

In addition to individual morality, there is “collective morality”, an opinion that a group of characters shares between them. It’s represented by the religion mechanic.

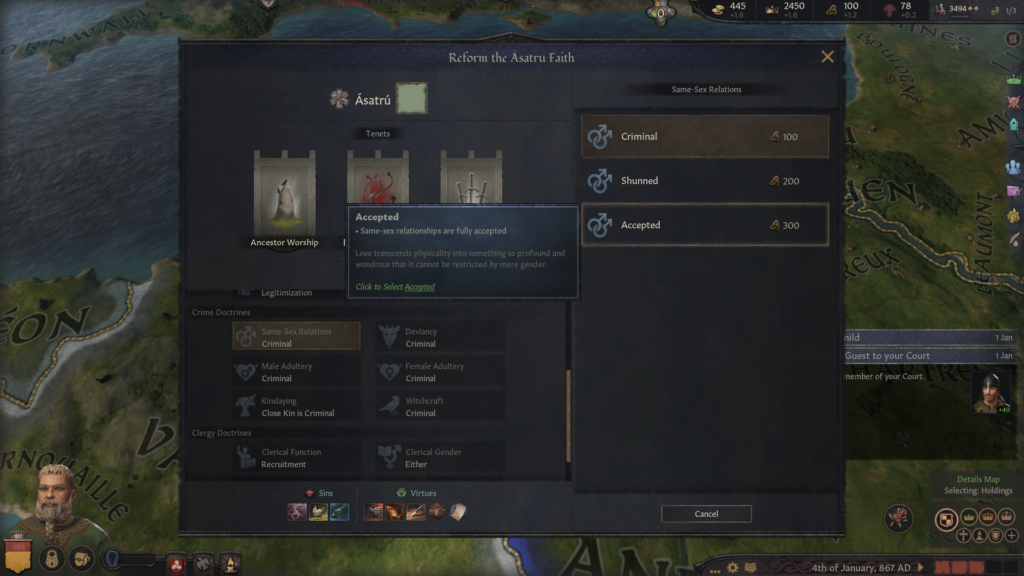

Each character has a religion with its own set of rules governing their views on the world. This includes extramarital affairs, consanguineous marriage, witchcraft, polygamy, and female role in society. The stance ranges from “Criminal” to “Accepted”. A ruler can legally imprison characters who engage in criminal acts. This can be advantageous if your rivals engage in criminal acts, but detrimental if you do so.

Each religion has its own set of virtuous and sinful traits. Virtuous traits increase opinion and boost Piety, an important resource in the game. Sinning, on the other hand, decreases opinion and results in negative Piety. The player can change religion and control what its followers believe, even making lying and murder praised within their religion.

Unlike Rimworld, however, the moral choice here is a bit more personal. Because the player has a clear in-game avatar, the decisions can be weighed against their own moral views. Even when I play characters with awfully amoral traits, I tend to avoid senselessly violent and evil decisions. Unless I am pressed by the mechanics to do it.

However, it can still be relatively easy for me to become a ruthless tyrant-torturer if I decide to try out that playstyle. Perhaps it has to do with character switching speed, because committing to evil in our next game is much harder.

Three opinions about same-sex relations in a religion

Dishonored

In each Dishonored game, a stealth-action series by Arkane Studios, you play as an assassin on a quest to kill several targets to save a dear person.

Player’s actions and playstyle affect the level of chaos, the game’s morality metric. Murder, detection, and engaging in some bonus quests like poisoning a bootleg plague medicine increase chaos. On the other hand, being stealthy and showing mercy to enemies decreases it.

The level of chaos has a direct impact on gameplay. The higher it is, the more enemies and environmental hazards there are on the map. It also affects the game’s ending, with a low level of chaos resulting in a more positive outcome and high chaos leading to a negative one. Low chaos is considered a “good” morality while high chaos is often associated with “evil” morality.

Chaos meter is overtly present in the game’s UI. The player always knows their level of chaos after each mission, and knows what it means from a tutorial. The player knows how their actions affect its level.

Chaos meter is always visible on the mission’s final screen

This creates a unique gameplay experience where the player’s moral choices influence their playstyle. If the player wants good things to happen to characters, they will skew towards the stealthy playstyle. It requires more effort but involves non-lethal takedowns, thievery, sleeping darts, and stealth-oriented runes (upgrades).

If the player doesn’t care about characters or wants bad things to happen, they will opt for the lethal playstyle, utilizing grenades, swords, and other lethal weapons and abilities.

Players who adopt a combination of both playstyles will get a “gray” ending.

The morality in Dishonored is therefore tied to a certain playstyle, with stealthy assassins having a positive outcome and lethal assassins facing regret in the end.

Out of the three cases presented in the article, I feel the closest connection to this game. Both Dishonored protagonists are relatively blank and allow you to shape their views. Naturally, their views are my views. This creates an interesting dilemma. I would love to do a lethal playthrough of Dishonored, really. I just can’t bring myself to do it, because I always want a good ending! Even for the villains. I’ve replayed Dishonored several times, and I always end up stealthing around.

***

So the closer the player feels to their game avatar, the more they will act according to their own morality. In detached grand strategy games or simulators, you feel comfortable enough to try out playstyles that don’t correspond with your views. This increases replayability. In RPGs with blank-slate characters, players are prone to making decisions in line with their own views. This decreases replayability, because the player’s views don’t change.