How to Reconcile Creativity and Management in Planning — A Case Study by Natalia Popova from Overmobile

On how to avoid chaos when planning new features — especially for App2Top, Natalia Popova, the manager of Overmobile's game team and the host of the course "Game Project Management" at WN Academy, shared her insights.

This article was published with the support of the educational service WN Academy, which actively attracts leading experts for its courses and corporate training.

Natalia Popova

My name is Natalia Popova, and I have been managing game development, mainly mobile, for over 15 years. In this article, I share my observations on how to balance creativity and management. Without bureaucracy, but not in anarchy.

In game dev, there is a stark conflict between creative chaos and structure. Both are important, but a tilt in either direction is risky. Here’s what many teams face:

RnD without releases

Creativity that lasts for years doesn't lead to results but consumes resources. "We didn't dive into a big project with unknown profitability," is a consolation that doesn't replace results.

A content factory without spark

An expanding team, entrenched processes, regular reports — and the creative impulse diminishes. A state of "no creativity" suddenly becomes a side effect of a game's success.

Chaos disguised as freedom

On the surface, there is creative freedom (the team generates non-standard ideas, there are releases), but internally, there are constant overwork, exhaustion of leads, wasted time, and lots of miscommunications. This isn’t creativity; it’s a lack of processes.

This approach is often romanticized: "we’re flexible," "we have a dynamic process," "we don't want bureaucracy." But in reality, it's chaos where people are prone to burnout, and the product is prone to failure.

A true creative environment is not anarchy but a place where an idea can be born and go through the path of realization without busting.

The manager’s task is not so much to control but to manage the events and ideas that continuously occur in a project. We will talk specifically about managing ideas.

For working with ideas, I propose the following chain: idea vault -> backlog -> iterative development.

I think every project manager has tried to create a backlog while studying Agile, but very quickly such a backlog becomes a dump and then a graveyard of ideas and notes.

Over the years of management in game dev, I have come to the following solution to this problem: before dealing with the backlog, it is necessary to introduce an element into the process that I call an idea vault.

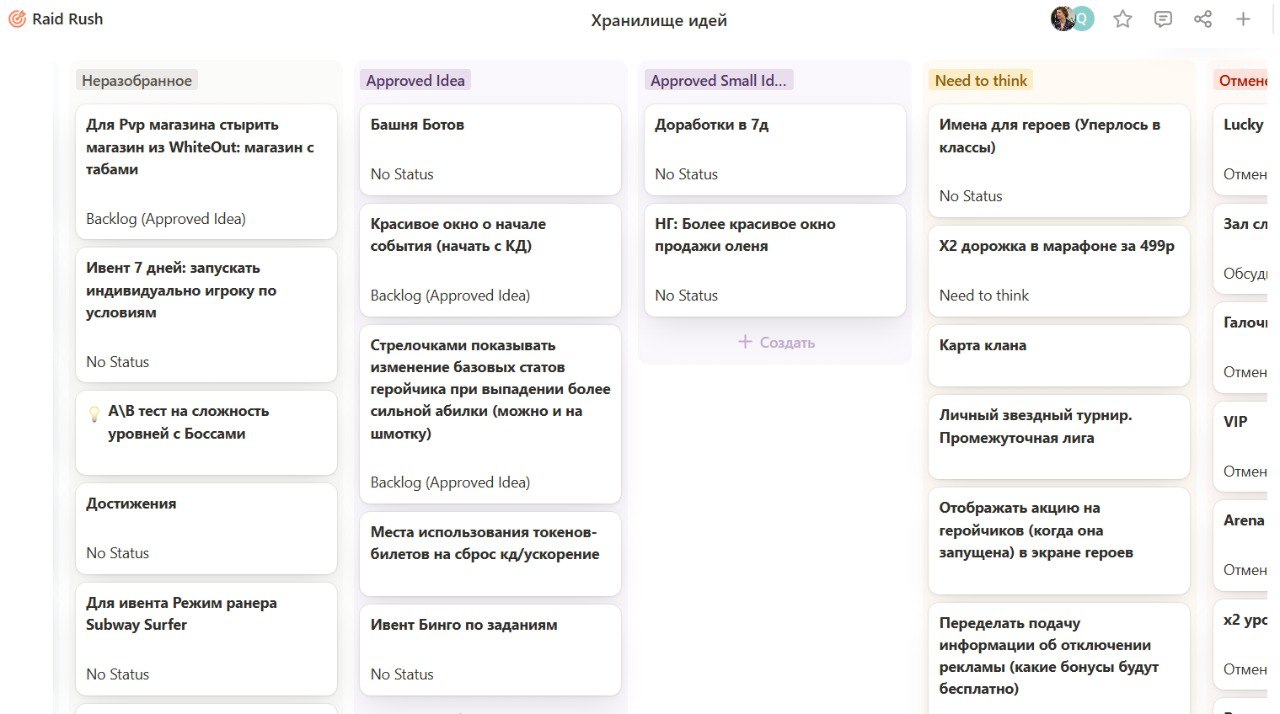

The idea vault is a board with cards divided into the following columns:

Inbox / Need to think / Approved / Approved small / Cancelled-Suspended

- Inbox — this column records all ideas voiced by the team.

- Need to think — this is for ideas that have questions and doubts. For instance, technical risks are visible, research is needed, there are questions about how to introduce the feature for old players, or there might be suspicions that the overall balance will break. I also put in this column ideas that appear too labor-intensive. In other words, this is a pool for ideas that you’re not ready to abandon, but can’t take into development without preliminary thinking.

- Approved / Approved small — these are proposals that can be turned into technical documents. I prefer to alternate between big and small ideas. In the programmers' work schedule, it often happens that between major features, small “intervening tasks” are needed.

- Cancelled-Suspended — it’s often hard for the team to abandon an idea when there is no apparent contraindication. Yet, from quarter to quarter, and even year to year, the idea remains in the vault. This means other ideas have been prioritized for a whole year. Such ideas logically need to be removed. This type of column helps keep the idea vault uncluttered but doesn’t force game designers to delete an idea immediately. An idea in the column for a year is much easier to part with than one that’s just added.

The horizon of detailed planning depends on the team and the project. Typically, it ranges from three to four months. Trends among features often emerge in the mobile market. A roadmap spanning half a year might become outdated by the time it’s realized. For this reason, I advocate for quarterly planning. Below, we will discuss what to do if the publisher requires a roadmap for a year.

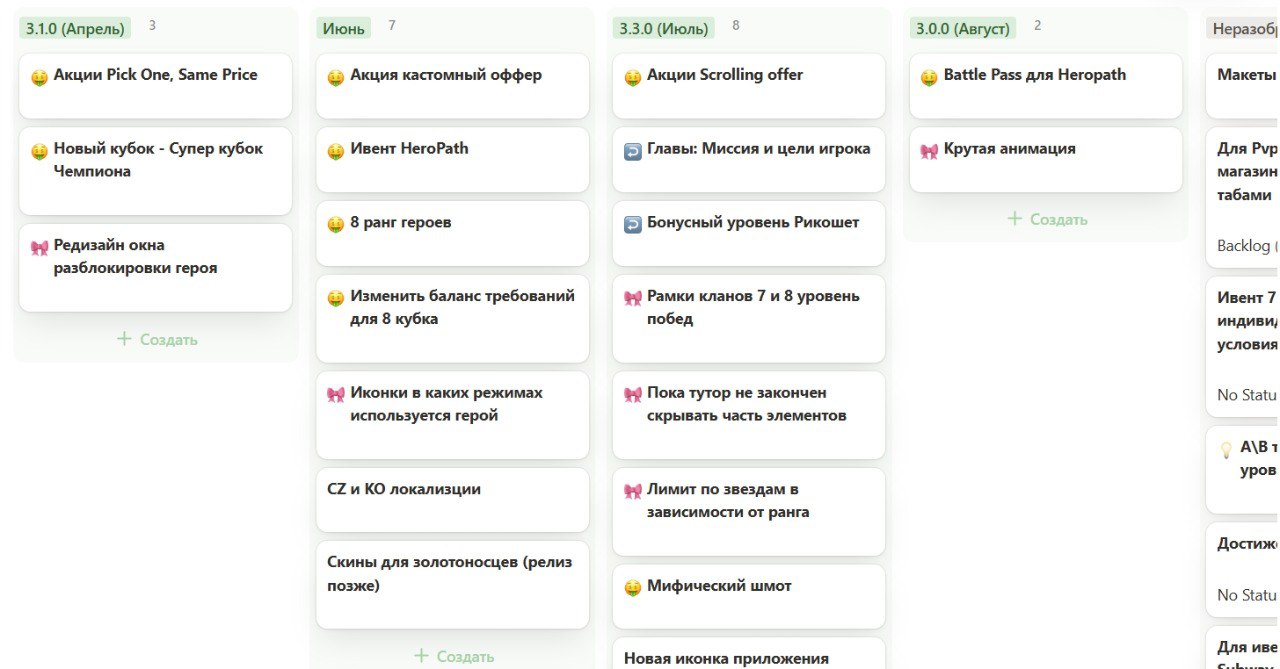

In the idea vault, we add columns by the number of planned releases per quarter (or per half-year if the team plans bi-annually). Releases in mobile games generally happen once every month or two. Therefore, we add three columns per quarter, placing them to the left of all the aforementioned columns.

Next, together with the GD/producer, we fill the three release columns with cards from Approved and Small Approved. In some cases, "far away" releases can include cards from Need to think. This way, it's clear when questions and risks on these cards need to be clarified.

This way of working with cards allows you to keep in one visual space:

- the high-level feature plan;

- a list of ideas for which technical documents can be written;

- a list of ideas for consideration;

- a list of all incoming ideas.

Over the years, I've concluded that it's crucial to keep such things in view simultaneously.

You might ask how to distribute idea cards across releases without time assessments?

Usually, with experience, a PM can quite accurately estimate the timeframe for most features. It’s unlikely that a feature will take a whole quarter, but a PM will estimate it as a month.

In any case, the plan's task is to determine the team’s priority work sequence. This is the product plan.

If the publisher requires a year-long plan, cards from the idea vault can similarly be distributed over the year: however, experience shows that it's worth revisiting the plan every quarter.

What other useful actions can be applied to such a plan-vault?

Good tools for organizing boards with cards offer emoji placement on cards. For example, I use:

- emoji with money/dollars — for features that directly influence monetization (at least as we believe);

- arrow emoji — for features aimed at improving retention;

- ribbon emoji — for features that contribute to overall product value but don't have a direct impact (e.g., “Replies in chat” or “Display player rank on a specific leaderboard”).

By placing emojis on cards, we check to ensure a release isn’t composed solely of ribbons. It’s easy to get carried away with such tasks — although product value is undoubtedly important, such tasks don’t fundamentally change a project’s metrics.

The second aspect to look at when reviewing release columns is the ratio of features for new players versus existing ones.

In this conflict of interest, beginners and entry funnel work are often "overlooked."

Overall, working on first-day retention, as well as first-day conversion, is more challenging and tedious compared to monetization and events for existing players.

Existing players are already there; they already write requests to support or the community. Emotionally, game designers are more engaged in interactions with them than with the percentage of players who will join when we improve day-one retention.

It is rarer, but possible, to forget about existing players. Therefore, always look at your release columns through the eyes of a paying player who has been in the game for a year: will the game provide new challenges and new dopamine?

Typically, both assessments reveal an imbalance in planned features: in this case, we once again pay attention to the Approved and Need to think columns to "rebalance" the releases.

Why is it so important to organize the process of working with ideas when they are not yet fully thought out?

I want to mention a vivid concept shared by one of Pixar's founders, Ed Catmull, in his book "Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration."

Over time, a Beast appears in the company: "by this, I mean any large group that requires a continuous flow of new materials and resources to function… It is relentless, it is hungry, and it always demands the next big project."

This seems to match the experience of teams with breakout projects: company growth and the growth crisis resemble the birth of the Beast. At this moment, managers can only keep up with feeding the Beast by giving all team members tasks.

Wait for a game designer to come up with a new feature idea unseen in other games? No time! 30 artists and 10 programmers are waiting for tasks!

Testing the idea? Discarding unsuccessful feature attempts? While we are not car factories with assembly lines, a frequent trap is the fear of team downtime, leading to planning "from people" rather than "from ideas."

Here’s how Ed Catmull describes an idea when it just emerges with the team: raw, awkward, like an unattractive child. At this moment, the idea is particularly vulnerable: it can be rejected, undervalued, broken, or frozen. That's why it needs protection, time, and space to grow.

I am fond of the vividness of these images, which apply to what happens in game development/support. A project manager should consider how to protect "unattractive children" from the Beast's teeth. Otherwise, the project might turn into an assembly line sustaining itself solely on existing players, gradually fading. Worse, many projects don't even make it to the loyal core of paying players.

A good idea can easily die. Sometimes under the Beast’s teeth, sometimes in a backlog no one revisits. Guard, organize, and manage your team's ideas even when they aren’t yet beautiful, understandable, or justified by charts — in many ways, creating such an environment is what true management is all about.